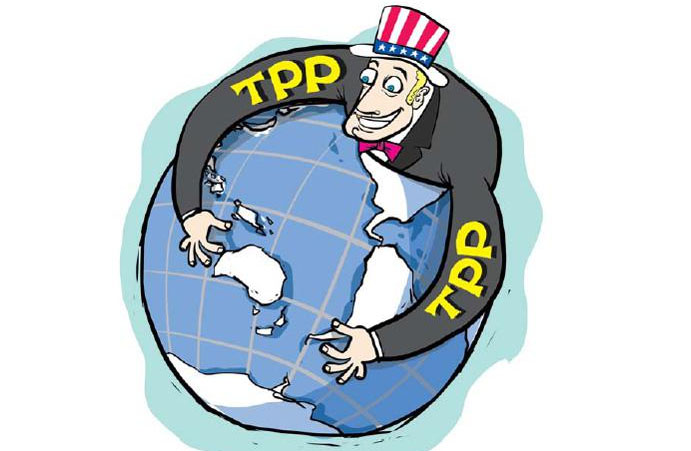

The recent conclusion of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) under the auspices of the United States has touched off a heated debate about its impact on China’s external trade and investment. Overall, the TPP is both a challenge and opportunity for China, as it comes at a critical moment when China tries to engage more deeply and widely in global governance.

The potential short-term impact of the TPP on China’s trade and economy as a whole is almost negligible, while the medium- and long-term impact depends on how China reacts to the TPP and handles its economic “new normal.” The TPP could even provide impetus for China’s efforts to deepen its economic reforms.

Perhaps because the stakes are simply too great to contemplate, the world is no longer being haunted by the specter of wars among major powers. The remaining competition among major powers is mostly relegated to global rule-making or global governance. The TPP is precisely one such example: It is about who will lead in global economic rule-making.

On surface the TPP is all about trade and investment, but more broadly, it is a smart move by the U.S. to set a higher bar for China in global trade and investment in the face of a more diverse picture of global governance. The TPP has thus become an economic instrument to carry out the “Asia-Pacific Rebalance,” brimming with geo-political implications. Through the partnership, the U.S. hopes to regain control of global trade rule-making as it has become uneasy about the growing influence of developing nations represented by China in such institutions as G20, WTO, and APEC.

Fortunately the TPP is only one of over 260 FTAs currently in existence; it can’t be everything at the same time.

From a purely economic perspective, when some economies form a tax union or FTA, there will be “trade creation” and “trade transfer.” Only the latter will be detrimental to outsiders, as trade barriers are reduced or eliminated within the grouping. So how much trade transfer will occur with TPP? Actually, not much because 80% of TPP members’ exports to the U.S. are already duty-free while even a bigger percentage of China’s manufactured goods enjoy that status. So by and large, the TPP tax change mostly affects agricultural produce from the U.S., Japan, Canada and Australia.

In addition, TPP members such as Australia, New Zealand, Peru and Chile have signed bilateral trade agreements with China. The China-ASEAN FTA covers Vietnam, Singapore, Brunei, and Malaysia. All of this greatly reduces the TPP’s negative impact on China. Another relevant point: Apart from NAFTA, American trade with TPP members amounts to a bit over $400 billion yearly while its annual trade with China tops $600 billion. That accounts for 10% of its trade as compared with 4.2% for Japan.

Most TPP members, except Japan and Australia, enjoy large trade surpluses with China. As long as China keeps growing under the “new normal” and with its new industrial base having consolidated in the last few decades, China will get an even greater share of the world market once the global economy fully recovers.

In sum, the TPP is more a psychological threat of “crying wolf.” It will likely have little impact on China’s foreign trade next year.

The TPP will mainly affect China’s medium and long-term domestic economic policy reforms. As a regional FTA, the TPP puts more emphasis on “within border” policies and rules associated with trade like IPR protection, labor standards, environmental protection, and SOEs than “on border” trade barriers.

Many of the rules the TPP covers certainly fall within the purview of further reforms in China. They seem pretty difficult to achieve in the short term, but not too much so as to be unreachable. TPP members include advanced and less advanced economies and many face the same challenges as China does. Take SOEs for instance. 40% of Vietnamese GDP is contributed by its SOEs, while Singapore and Malaysia have similar percentages. If they can cope with TPP rules on SOEs, China should have no major problems either.

Many TPP rules represent current trends in global trade and eventually will be accepted by the world. These new standards might bring great challenges to China’s efforts to upgrade its industries, but in the end they could also be opportunities for China to pursue further economic reforms in the coming years. China must play its due part in the global rule-making in free trade and investment, instead of being led.

China will not be able to join TPP because the U.S. and Japan are opposed to it, although China and the U.S. say both are open to China membership. For that, China needs to be cool-headed and take the following steps among other things to meet the challenge posed by TPP.

The first step is to deepen reforms already in the pipeline. It is advisable to quicken the pace of four major domestic FTA experiments covering Guangdong, Fujian, Shanghai and Tianjin. A great deal of innovations will occur in these areas and they should be quickly copied nation-wide. That will lay a good foundation for future moves of either joining TPP, or having TPP merge with other regional FTAs. We are entering a new era of global governance and remolding of trade rules, which should be viewed as a good opportunity for China rather than a threat in globalization.

As China engages ever further in global governance, more new rules will present themselves and it ought to be ready for such scenarios. China should further reform its financial system and reduce costs for funding the real economy in order to elevate industrial competitiveness. It should also deepen reforms of SOEs and develop better mixed-ownership in enterprises to expand foreign trade. It needs to continue improving labor conditions so that a balance of decent work and better ecological and environmental effects can occur. The TPP is more about global governance, and should be treated as such.

The second step is to offset any negative consequences of the TPP by proactively pursuing other regional initiatives, given the fact that China will assume the rotating chair of the G20 in 2016, and enjoys great influence in regional institutions like APEC.

China should more vigorously pursue FTAAP negotiations, quicken the pace of a China-Japan-South Korea East Asia FTA, and conclude negotiations of the RCEP by the end of 2016.

The third step is to put the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative into practice as quickly as possible. Efforts should be made to pursue policy dialogues with countries along OBOR to adapt developmental strategies with one another. Major partners like Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia and Pakistan should be consulted first. Such new financial institutions as the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and Silk Road Fund should be brought into full play—based on internationally accepted rules—to boost cooperation on redistribution of production capacities. President Xi Jinping’s visit to the UK provides further impetus for greater European inputs into the OBOR initiative.

The fourth step is to manage China-U.S. relations in a way that will help OBOR rather than impede its implementation. The recent successful state visit to the U.S. by President Xi demonstrates that the U.S. is better prepared now to accept OBOR as a platform for bilateral cooperation. That is certainly good news for all involved to shed the TPP of “the geo-political coat” that it should not have worn in the first place.