Source: National Bureau of Statistics, China, various years

State-sponsored actions of Chinese firms along with the role of Chinese and local government leaders in recipient developed countries are two crucial elements of the ‘colour of Chinese money’. This phrase conveys the range of responses to Chinese capital flows—into real estate, education, industrial investments, research and development, even government propaganda campaigns,— and the variety of responses to the connotations of Chinese involvement in their economies, whether real or imagined.

What is certain is that by virtue of the primacy of the state as an actor in China’s highly politicized economy and the increasing size, importance and implications of Chinese investments, trade and the foreign business benefits of market access to China, the partner countries’ political institutions have been increasingly drawn into the dynamic.

Dealings with an expanding and increasingly outward facing China have placed foreign leaders in a position whereby public engagement with China on investment and trade issues can cause a perception of either pragmatic collaboration for mutual strategic and economic benefit at best or collusion and corruption at worst.

If China has a formal state-to-state engagement strategy, then China’s domestic and foreign service infrastructure must also support the objectives of the ruling Communist Party of China (CPC). Chinese investments and international trade arrangements are for the most part inextricably tied to the state, both through frequent direct or indirect ownership of companies by the state and by the continuing embeddedness of the Chinese Communist Party either within or closely linked to the success of Chinese companies.

This often puts top politicians from recipient countries into the bilateral bed with top politicians from China whose role by its nature involves the promotion and maintenance of CCP power. Recent examples include President Xi Jinping’s state visit to the UK, including transportation by way of golden coach to Buckingham Palace (and his address of the UK parliament in 2015); his visit to Donald Trump’s resort in April, 2017; Premier Li Keqiang’s visit to Australia in March 2017 and Xi’s appearance both at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2017 and at the G20 in Hamburg last week. The role of the state and its leaders in these bilateral dealings and high level meetings seems to be of great interest to corporations, policymakers, China researchers and the public.

China presents its political leadership on the world stage such that an impression of success in economic friendship diplomacy (EFD) is projected inside and outside of China, mitigating failures in earlier communist-branded friendship diplomacy. Chinese leaders’ very presence and acceptance on the world stage with other world leaders creates a sense of Chinese political success, global business and economic leadership, contributing both to Chinese public diplomacy and domestic propaganda. China’s actual success has tended to reside in obtaining favours in economic decision-making. This is manifest in China’s insertion into the economic policies of other nations. However, the implication is that those countries are to some extent condoning aspects of the Chinese regime—areas of behaviour and policies of the Chinese state that are still sources of political friction.

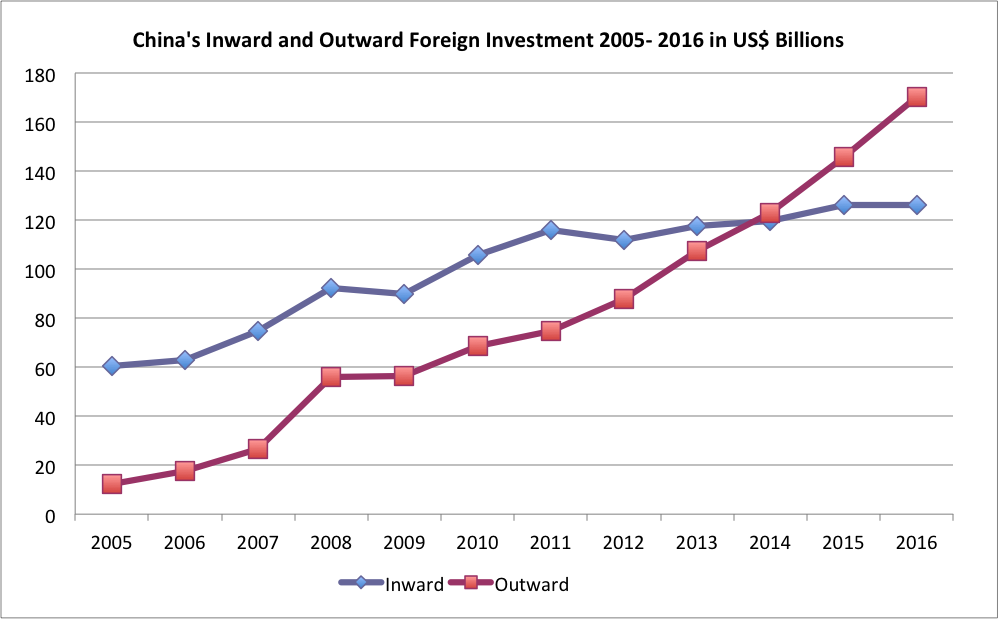

Reactions to the evolution of Chinese outward investment have ranged from academic disdain about the petty levels of Chinese FDI stocks relative to media sensationalism to deep and very genuine political and security concerns for countries either trying to create more valuable economic links with China or countries already embedded in bilateral investment and trade relationships.

Australia’s concerns about the nature of Chinese investments into strategic industries were encapsulated by the blocking of the Ausgrid electricity provider deal or even deals in less strategic areas—e.g. the land asset based investment into the 40,000 square mile S. Kidman & Co cattle fields—in addition to the furore around the blanketed Darwin port investment by the allegedly PLA-affiliated Landbridge Group.

Conventional wisdom might have us expect the 400 million euro joint venture between CGM-Terminal Links, France’s biggest shipping company, and China Merchant Holdings, who purchased 49% of the French counterpart, effectively giving them a controlling stake over ports around the world, would be met by a negative reaction in the States, such as occurred with UAE’s Dubai Ports rejected deal in 2006—ironically a deal for lower aggregate container flow at a higher price. Securing ports like Miami and Houston ought to lower transaction costs of shipping and container management, and partner-shipping with one of the world’s largest shipping and container companies offsets and mitigates risk for China’s own merchant vessels by diversifying out the risk. If, due to some incident of sanctioning on the high seas, Chinese merchant vessels were targeted, China has not only have spread its bets in financial terms for its large state-owned enterprises by way of ports and shipping investments, but has secured control over port functionality and access to the use of different trade routes. On the one hand such deals reflect globalisation, global integration and cooperation within the shipping industry. On the other hand such deals have the potential for substantial political reaction, such as in the case of the Darwin port scandal. Given the indirect ownership of Houston and Miami by the Chinese state this may demonstrate either limitations or areas for improvement in U.S. control over market processes.

However, Chinese deals are often welcomed as investments and precursors for local and bilateral trade. In light of the aftermath of the financial crisis, for instance, European countries have been more open to Chinese investments than previously due to lowered political resistance, lower employment, depressed prices, and economic incentives for China such as moving up the value chain. Although granting China market economy status was eventually deemed a step too far, the Chinese yuan RMB currency was granted special drawing rights (SDR) with the world bank in September 2016, to the great pleasure of Chinese policymakers, international relations think tanks and the government.

Such events demonstrate both the opaque nature of some political and diplomatic dealings and that they can easily lead towards a perception of collusion rather than of pure collaboration with China. In terms of the politics, high-level politicians have embraced the showcasing style of the Chinese leadership, implying some sort of shift in trust and a willingness to engage with China, although generally not shown by manifest alterations to foreign policy. Chinese diplomacy has played a central role in facilitating investments and trade, not only in terms of formal ties such as memoranda of understanding, frequent trade-focused political summits and free trade agreements, but also in high-level official meetings between heads of state or ministers.

A greater role for government officials and leading politicians and ministers in the agreement processes that support the China bilateral trade, investments and other capital flows will be undoubtedly welcomed by high level foreign officials. This may be easier said than done, if some businesses actively seek to avoid the presence of a minister at the signing of important deals. However, as the role of government increases and gains credibility on the public stage, this could increasingly become the norm.

Political and economic institutions locally and globally are inextricably linked in the outside world’s dealings with China and in China’s dealings with the outside world. For any significant deal, political intervention is deemed necessary because of a perceived risk to those the polity is supposed to serve—and yet it is at times potentially beneficial for the politicians and economic actors involved to engage Chinese counterparts and entertain Chinese ambitions. The potential disruption to economic equilibrium and the risks to national interests and security in addition to grass-roots political concerns mean that stakeholders, in consideration of deals with China, necessarily include the public in addition to businesses. This puts political forces closer to business transactions and in positions of heightened responsibility, requiring specialist analysis and intelligence to balance the uncertainty around the consequences of their decisions.