According to the announcement, “The THAAD deployment will contribute to a layered missile defense that will enhance the alliance’s existing missile defense capabilities against North Korean missile threats.” The upcoming THAAD deployment, scheduled for the end of 2017, will help protect U.S. and ROK military personnel and assets on the Korean Peninsula as well as the South Korean population from North Korean missile strikes by adding another layer to Seoul’s missile defenses. THAAD can engage North Korean missiles at a considerably higher altitude than the Patriot missile defense systems in South Korea—the kind of ballistic trajectory DPRK missiles aimed at South Korea’s southern ports might follow. With effective detection, tracking, and interception technologies and command and control systems, a THAAD system on South Korea could also provide an additional opportunity for the defenders to engage North Korean missiles before the PAC-2 and PAC-3 batteries attempted a lower-altitude interception.

The decision followed years of delays during which Washington and Seoul strived but failed to curtail the nuclear and missile buildup of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’s (DPRK) through diplomacy and sanctions, including in partnership with China and Russia. Since the beginning of this year, North Korea has detonated its fourth nuclear explosive device, which Pyongyang claimed was a hydrogen bomb, and tested numerous missiles of varying length, including a Musudan (Hwasong-10) intermediate-range ballistic missile a few weeks ago. The Musudan can reach a height of 1,400km and has a range of 3,500km—a flight envelope beyond the ROK’s Korea Air and Missile Defense (KAMD)’s limited capabilities of intercepting short- to medium-range ballistic missiles.

The Defense Department’s announcement stressed that the new THAAD system “will be focused solely on North Korean nuclear and missile threats and would not be directed towards any third-party nations.” Nonetheless, the Russian and Chinese governments have attacked the decision on various grounds.

For example, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Igor Morgulov denounced what he called a “buildup of the U.S. global anti-missile potential in [the] Asia-Pacific and an attempt to change the existing balance of power.” He claimed that the step “will inevitably lead to escalation in Northeast Asia and hinder settlement of the Korean Peninsula problem, including its denuclearization.”

The Chinese Foreign Ministry went even further and demanded that Washington and Seoul “halt” the planned THAAD deployment. Spokesperson Lu Kang called the measure “selfish” and claimed that the deployment would threaten peace and stability, escalate tensions on the Korean Peninsula, and “gravely damage the strategic balance in the region as well as the strategic security interests of countries in the region including China.” In addition, Lu threatened “necessary measures to safeguard [Chinese] interests if the United States and ROK don’t stop the deployment.”

John Kirby, a State Department spokesperson, said that the United States has “listened to their [Chinese] concerns and we have offered to provide informational briefings for them on the way the system works.” U.S. officials also made the same offer to Russia. However, such briefings have not proved fruitful since Russian and Chinese interlocutors distrust the message and the messenger. Regardless, their opposition to U.S. Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) is driven mostly by geopolitical rather than technical considerations.

It is true that both Russian and Chinese military planners can postulate scenarios about how missile defenses could facilitate a U.S. first strike against their nuclear deterrents. Furthermore, Moscow and Beijing depend on their large and varied missile arsenal to deter foreign military actions against them, intimidate other countries, and keep foreign militaries away with asymmetric anti-access and area-denial capabilities.

The THAAD is designed to intercept short- and medium-range missiles or their warheads when they are descending toward a nearby target. It is incapable of intercepting Chinese Intercontinental-Range Ballistic Missiles aimed at the United States or even shorter-range systems launched from China in a different direction, such as against Taiwan or Japan.

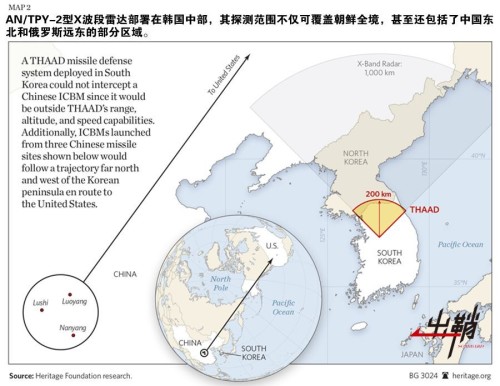

Chinese officials claim that THAAD’s sophisticated AN/TPY-2 X-Band radar could markedly improve the U.S. ability to monitor Chinese territory and, in particular, acquire intelligence about the capabilities of China’s nuclear missiles. But its capabilities should not be exaggerated. The THAAD in the ROK would be stationed at the farthest end of the peninsula away from China; likewise, it would be kept in “terminal/engagement mode” to monitor North Korean missiles rather than peer deep into China. Even if THAAD could monitor Chinese capabilities, the insights gained from the radar would hardly matter since the United States already collects enormous data about Chinese military activities through air, sea, space, and cyber-based sensors as well as human assets within the Chinese military and government. China is actively seeking the same capacity against the United States.

Regardless of the technological issues, Russian and Chinese representatives have expressed general concerns about how THAAD could affect strategic stability, alliance relations, and global influence. They warn that Pyongyang will respond by accelerating its offensive missile buildup because the deployment will make North Korea feel more insecure. They call on Washington and Seoul to work in partnership with Beijing and Moscow to solve regional security threats like North Korea rather than taking actions, such as THAAD deployment, that ignore and allegedly harm Chinese and Russian security.

The Russians and the Chinese accuse Washington of exploiting the threat from North Korea to justify expanding U.S. military presence and capabilities near their territories and encouraging U.S. friends and allies to increase their own defenses. They also oppose THAAD and other U.S. military measures that strengthen U.S. alliances by making them more effective and interlinked. They might hope that by blocking U.S. allied missile defense cooperation, they can incite tension in the alliance and weaken the credibility of U.S. global defense guarantees.

The Chinese might also be irritated that their efforts to court favor in Seoul failed to prevent Seoul’s deployment decision. But the Chinese government’s full-court press in Seoul to deter South Korea from agreeing to the deployment backfired. China gave the impression of trying to control South Korea’s national-security decision making and weaken the ROK-U.S. alliance by leveraging the THAAD issue to divide them. Fortunately, China looks to be resisting the temptation to relax enforcement of UN sanctions on North Korea or to curtail economic and social ties with South Koreans, who want good ties with China and to partner with Beijing to solve their common DPRK problem.