A systematic escalation of terror has begun in Asia. In May, an armed conflict started in Marawi, Mindanao, where government forces were surprised by the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant (ISIL), and homegrown Maute and Abu Sayyaf Salafi jihadists.

After a foiled plot by an ISIL-linked group last year to launch a rocket at Marina Bay Sands in Singapore, several radicalized Indonesian workers have been sent back home and Bangladeshis arrested, along with a few Singaporeans.

In late July, four terror suspects were arrested in Sydney, Australia, for planning to blow up an Etihad plane and a set off a toxic chemical gas attack in a public place. Indonesia and Australia have hosted a counter-terrorism meeting with Malaysia, Philippines, and New Zealand. Security has been tightened in Kuala Lumpur ahead of the upcoming 2017 Southeast Asia Games and ASEAN Para Games.

In early August, the Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (IPC) said that a small but alarming number of Indonesian maids working in Asia are becoming radicalized for the Islamic State (IS). While there are 150,000 Indonesians living in Hong Kong, the PIC uncovered a cell of 43 radicalized maids living in Hong Kong, three in Taiwan, and four in Singapore. Due to elevated concerns for terrorism, some 14,000 travellers from Asia Pacific were barred from Hong Kong in 2016.

As evidenced by the Manila Summit, the Association of the Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is uniting against the threat of homegrown terrorism. A decade and a half after U.S. invasion of Iraq and half a decade after the West’s military interventions in the Middle East, Jihadi terror is pivoting to Asia thanks to years of complacency in the region, the U.S. pivot to Asia, and the ISIL collapse in the Middle East.

ISIL pivot to Asia

In June 2012, just months after the Obama administration’s pivot to Asia, the Khilafah, a major jihadist website, warned that since “the US will shift 60% of its warships to the Asia Pacific, over the coming years until 2020,” it was time to bring Islamic power in the region. Historical and geographic forces fuel the upsurge. In March 2016, Wikileaks released U.S. diplomatic cables dating back to 1979, which highlight the efforts by the CIA and Saudi Arabia to plough billions of dollars into arming the Afghanistan fighters against the Soviet Union, which according to Julian Assange paved the way to al-Qaeda and eventually the ISIL.

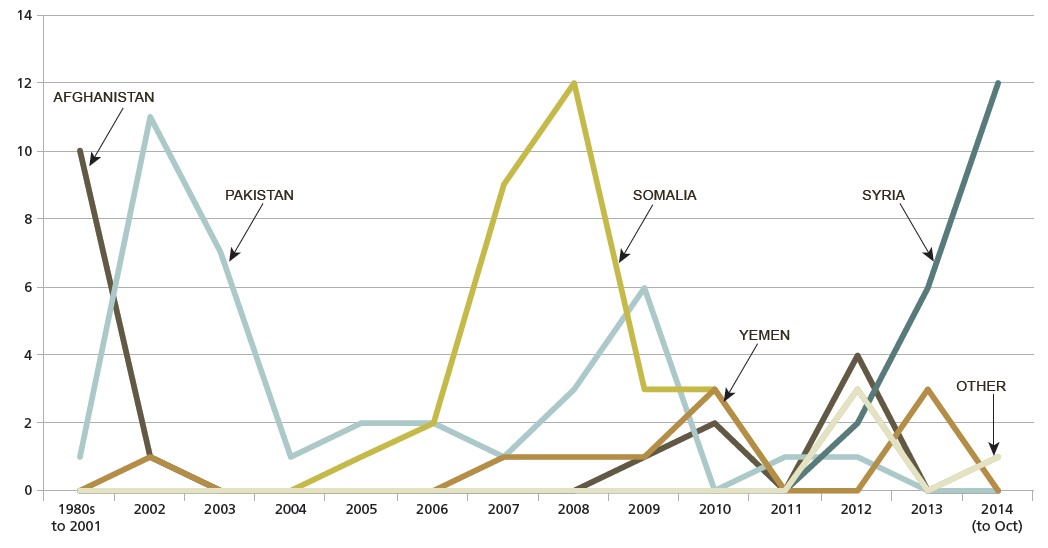

Ironically, that view is supported by U.S. counter-intelligence. Historically, Jihadism originates from a few historical destinations. In each case, U.S. interventions have caused destabilization, which has supported the spread of terror.

In Afghanistan, the CIA relied on “Operation Cyclone” to arm and fund the mujahideen around 1979-89. Until 2001, it remained a key destination, where volunteers went to join al Qaeda or the Taliban. After the U.S. overthrow of the Taliban government, Pakistan became the preferred destination. In 2006, U.S.-backed Ethiopian troops invaded Somalia, which led to a three-year war attracting a new wave of Jihadists to the region. In the Syrian Civil War 2011-17, the U.S., in cooperation with its NATO allies, played a direct role until recently, while collaborating with “moderate jihadists.” In the ongoing Yemeni Civil War, the U.S. has provided intelligence and logistical support to Saudi Arabia, which has attracted Al Qaeda and ISIL in the region (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Intended Destinations of Would-Be Jihadists Over Time

Source: RAND, 2014

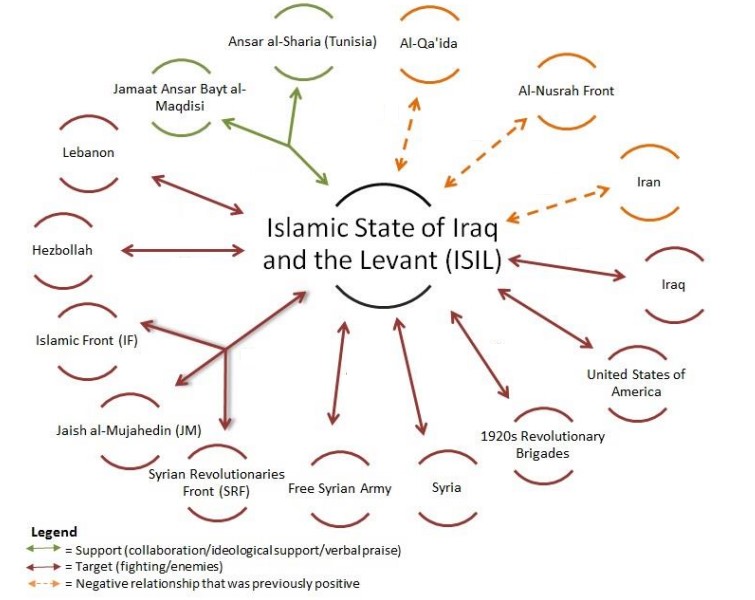

Yet, these pre-ISIL footholds of terror were largely regional. Wars in Iraq and Syria changed the status quo. These battlefields are causing major international spillovers, especially when the fighters would return home (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Internationalization of ISIL Relationships Since 2004

Source: START, 2014

Today Mindanao, tomorrow Asia

In March 2016, then-President Aquino stated that the Islamic State had no presence in the Philippines. In fact, the ISIL had had a foothold, training and loyalists in the country at least since late 2015, and Jihadi sympathizers since the early 2000s.

In the Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), the Moros (the Philippine Muslims) have witnessed colonial violence by Spain, America, and Japan; several communist insurgencies; armed Moro separatist movements; and now terrorist attacks. Though resource-rich, the region is impoverished. In metro Manila, real per capita income is 17 times higher than in the ARMM, where it is on par with the per capita income of Afghanistan. For years, Jihadists have hoped to exploit the resentment of young Muslims in the ARMM to create a new Syria in the heart of Southeast Asia. With foreign fighters, the effort has entered a new stage.

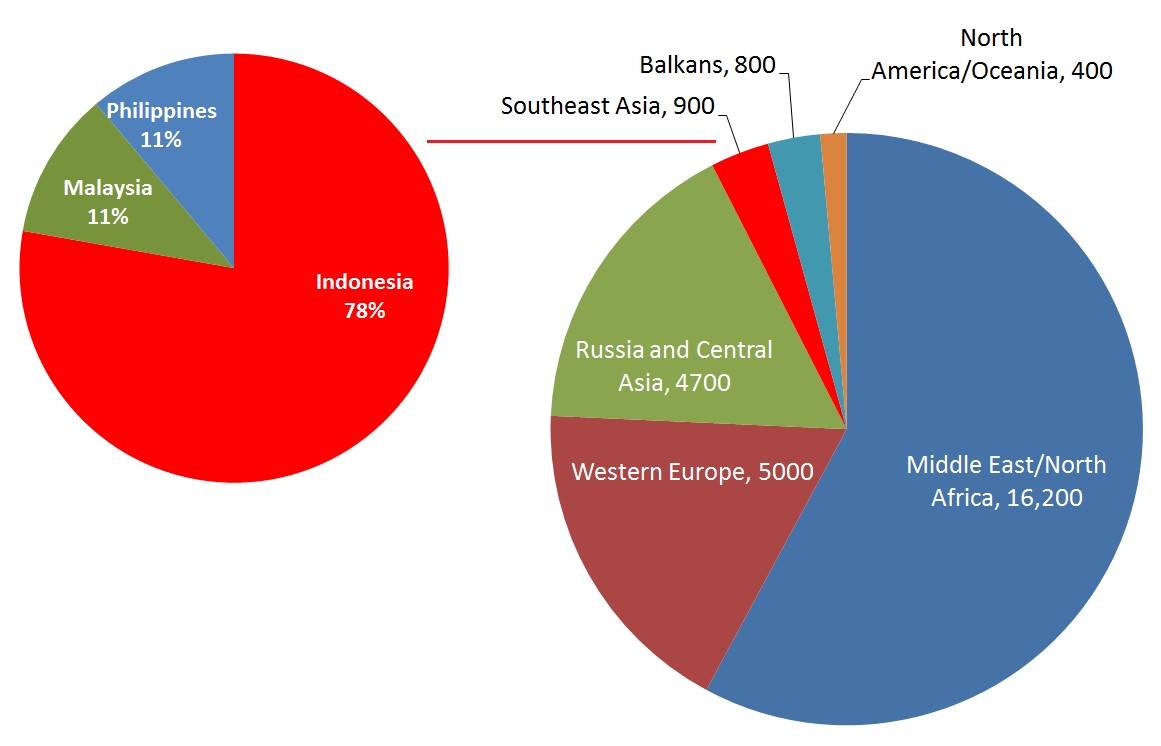

According to the Soufan Group, 27,000-31,000 people have traveled to Syria and Iraq to join the ISIL or other violent extremist groups from at least 86 countries. As Western efforts to contain the flow of foreign recruits to extremist groups in Syria and Iraq have dramatically failed, the average rate of returnees is at 20%-30%, which presents an urgent challenge to security and law enforcement agencies. Hardened attitudes against immigration and minorities have made the status quo still worse.

By the year-end of 2015, almost 60% the foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq came from the Middle East and North Africa, while nearly 20% originated from Western Europe or Russia and Central Asia. The rest came from Southeast Asia, Balkans, North America and Oceania. Indonesia accounted for four of every five from Southeast Asia, while the rest can be attributed mainly to Malaysia and Philippines (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq by Region (Year-end 2015)

Source: Data from the Soufan Group, 2016

Source: Data from the Soufan Group, 2016

In Indonesia, there are reportedly ISIL cells in most villages. In Malaysia and Singapore, the resentful cluster in discontented quarters. In the ARMM, jihadists comprise a tiny group of extremists that oppose the peace process – for now.

According to data by West Point’s Combating Terrorism Center (CTC), most foreign fighters have limited familiarity with Islam, although in recruitment, peer groups and religious mentors play a key role. Most have less than 12 years of schooling. One third is unemployed, another third employed but stuck in low-skill jobs. Three of four foreign fighters are 18-29 years old and recent arrivals in host countries. Almost all have no military experience prior to recruitment. And while very high percentages die in operations, only one in ten have died from suicide operations.

The rise of foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq can be attributed in part to the military interventions of the U.S. and NATO in the Middle East; in part to the gross failure of the West to integrate Muslim immigrants with education, jobs and mobility.

Development or terror

Currently, the outlook for Asia remains robust and recent data point to a pickup in momentum. The region may reap the benefits of peace and economic development in the coming decades - but only if the threat of terrorism can be neutralized.

Here's what the region needs:

1. Restoration of peace and stability in the terror clusters. The Duterte administration’s effort to pacify terror in ARMM is absolutely vital, including the extension of the martial law. The threat must be neutralized now when it is still marginal, soft and fragmented; and most locals supports government efforts to restore peace and stability. Pacification and stabilization is not possible without cooperation with neighboring countries that share similar threats, particularly Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore.

2. Acceleration of economic development across Southeast Asia. In the medium-term, it is equally vital to escalate all efforts at economic development, through the stabilization of current key cities and regions, by prioritizing Economic Corridors in Mindanao, West Borneo, including Sabah and Kalimantan, as well as Greater Sulu Sulawesi, and Papua-Maluku Island.

3. Medium-term regional economic and strategic integration. Accelerated ASEAN integration can foster peace, stability and development in key economic corridors, but also in the context of the China-led One Belt One Road Initiative, which is intensifying economic development from East, South and Southeast Asia to Central Asia and the Middle East.

4. Long-term cooperation with major Asian and Pacific powers. This is vital in economic development (foreign investment, trade and investment, and aid), ASEAn economic integration, and defense. It requires collaboration with China and the US, but also with Russia, Japan and Australia, as well as Saudi Arabia, Iran and Egypt – the regional powers in the Middle East.

In Asia and elsewhere, terrorism preys on social exclusion, economic impoverishment and hopelessness. It cannot be averted without inclusion, development and hope.