When the video of President Trump’s insult to NFL players for kneeling during the national anthem was released on Weibo, China’s equivalent of Twitter, it went viral. In one week from the day of its release, four thousand people retweeted it, around eight thousand commented on it, and the video accumulated twenty thousand likes on Weibo.

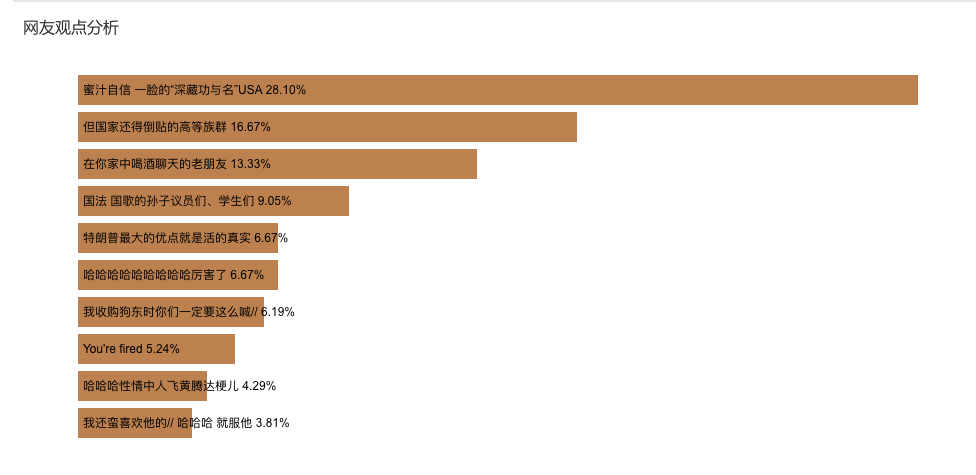

Many of the comments left on the video espoused support for President Trump and his remarks. “The biggest appeal of Trump is his frankness” reads the top comment that garnered more than ten thousand likes. “For those who refuse to stand during the national anthem, who are contemptuous of the state, they deserve to be fired, even put into prison,” says the second most-liked comment. In fact, among the top ten most popular comments, only one can be categorized as being even mildly critical of Trump. The comment explained the fact that NFL players knelt in protest against racial injustice. But the comment was quickly followed by hundreds of racially motivated attacks on African Americans. A breakdown of Weibo users’ comments on the video reveals that the overwhelming majority of users had a positive reaction to Trump’s criticism of NFL players.

Trump is not new to being an Internet celebrity in China. His grimace has been made into hundreds of memes on Weibo, and sound bites of his speeches have been remixed into rap songs and circulated on the Chinese Internet. A Chinese news website, Huanqiu, compiled an online poll after the first presidential debate between Hillary Clinton and Trump, asking Internet users for whom they would vote if they had the chance. Surprisingly, 86.7% supported Trump while only 13.3% responded in favor of Clinton.

Weibo used to be the only place to find vibrant sources of debate in China. But in recent years, Weibo has become the platform of choice for nationalism, xenophobia and racism. Today, Weibo users have two labels for those they consider to be in the habit of lecturing them on “political correctness”— the “public intellectual” (公知 Gong Zhi) and the “saint bitch.” (圣母婊 Sheng Mu Biao)The invention of these two terms speaks volumes about the evolution of discourse on Chinese social media in recent years.

In 2013, there was a national campaign designed to undermine the credibility of the group known as the ‘Big V’ bloggers on Weibo, namely users whose followers exceed a certain figure, giving them wide public influence as opinion leaders on the Chinese Internet. Many ‘Big V’ bloggers used to be vocal on social issues in China. For example, Charles Xue, an investor-turned-public intellectual, used to be openly critical of food safety and government corruption. Thereafter, Xue was charged for soliciting a prostitute and his confession was broadcast on national television. The fact that he was a naturalized U.S. citizen was widely circulated, as well.

Around the same time, similar scandals surrounding other ‘Big V’ bloggers were widely reported. Following the public dissemination of the details of their personal scandals, ‘Big V’ bloggers lost their moral authority in the eyes of Weibo users. The phrase “public intellectual’ became a derogatory term, referring to those who incessantly lecture others on morality without adhering to the standard themselves. This led to the growth of contempt for intellectualism, the preferred method of engagement that public intellectuals stand for. Moreover, it produced not just a rejection of intellectualism, but also an open hostility towards knowledge in general.

In many ways, the contempt for intellectualism and moralism on an individual level parallels with that on the state level. For years, the Chinese government has rejected the West’s imposition of human rights standards, and has objected to being forced by many Western countries to share the burden on issues like climate change and the various refugee crises. The government has argued that China, as a developing country, could not deal with crises created largely by developed countries. For example, an op-ed published by the former Chinese Ambassador to Egypt and Saudi Arabia, Wu Sike, argues that the attempt by the U.S. and its allies to pursue democratization in the Middle East is what created the refugee crisis in the first place. Similarly, when it comes to climate change, for years before the Paris Agreement, China argued it should not be expected to shoulder the same strict caps on its greenhouse gas pollution as Western countries.

During the 2015 European refugee crisis, when Angela Merkel was attacked domestically for her decision to accept Syrian refuges, Weibo users coined the word “saint bitch”(圣母婊 Sheng Mu Biao)to describe her, arguing that she merely chose to open up Germany’s borders for her own political gain. Thus came the alignment between the rejection of intellectualism and moralism at an individual level with that at the state level. Not only should individuals or states refrain from lecturing on Chinese Internet users, but foreign states should also avoid trying to dictate to China how it should behave. These two phrases point to both an outright assertion of autonomy and to a rejection of moralism and intellectualism coming from a person of authority.

In this context, it is not a surprise to see Trump enjoy public admiration by Chinese Weibo users. His contempt for formality, norms, and political correctness all strike a nerve with Chinese Internet users. In the video of Trump lambasting NFL players, Weibo users translated the audience chanting, “USA, USA” to mean that, “the U.S. will be the greatest, and Trump will be the king(大美兴 川普王 Da Mei Xing, Chuan Pu Wang)”. No wonder so many Weibo users changed their usernames to ‘Trump the Boss’ following the 2016 election.