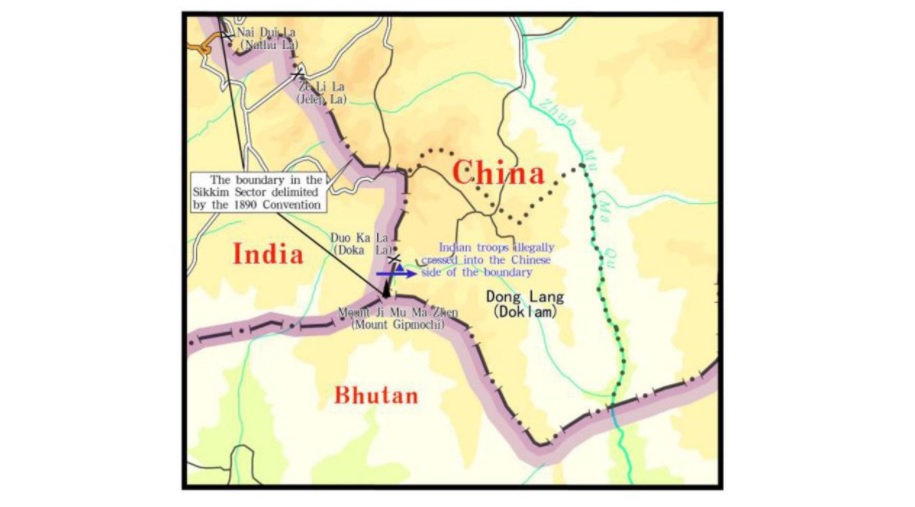

On June 16, 2017, normal road construction was underway on the Chinese side of the Donglang border area of China’s Tibet Region. On June 18, some 270 armed personnel from Indian border units, carrying weapons and driving two bulldozers, crossed the Doka La Pass at the Sikkim section of the border and penetrated over 100 meters into China, resulting in a disruption of the construction and greater tension in the area. The Chinese side has made repeated demands for immediate withdrawal of Indian border forces. But to date, there is still a sizable presence of Indian forces on Chinese soil. What’s more, to confuse world opinion, the Indian side has cooked up quite a few excuses that are contradictory and completely untenable.

First, India tries to justify its illegal trespassing by accusing China of creating “serious security risks” by road construction. As part of China, Donglang has always been under effective Chinese administration and control, supported by a large body of international treaties and diplomatic documents. For example, the 1890 Sino-British Treaty on Sikkim has explicit provisions to that effect. In his correspondence with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai on March 22 and September 26 of 1959, then Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru recognized in clear terms that there was no discrepancy on the boundary between Sikkim and China’s Tibet region. This position was reaffirmed by the Indian side in the 1960 note from the Indian embassy in China to the Chinese Foreign Ministry and the Indian document submitted on May 10, 2006 to the China-India Border Issue special representative working group. Facing mountains of evidence, India has been compelled to tone down its rhetoric and no longer argues that all sections of the China-India boundary are contested. But it remains wedded to its “security concern” argument. That argument, however, is even more ludicrous. If a country was allowed to cross the delimitated boundary into its neighbors’ territory on grounds of perceived security concerns, the world would soon become a madhouse. The international community can never tolerate such blatant provocation of international law and basic norms of international relations.

Second, India is acting as a self-appointed “big brother” of Bhutan. In its June 30 statement titled “latest developments of the Doklam situation”, India’s Foreign Ministry alluded to its fantasy that when “Bhutan’s military was trying to block China’s road construction in Donglang”, India, as Bhutan’s “suzerain authority”, was duty bound to enter the Donglang area on its behalf. The problem with this excuse is that Bhutan has never asked India to intervene militarily on its border issue with China. Since China and Bhutan started negotiations in the 1980s for a settlement of their border issue, 24 rounds of talks have been conducted. Though no official delimitation has been achieved, both sides share a basic agreement on the alignment of their common borders. Situated between China and India, Bhutan has no intention of siding with one against the other.

Moreover, such terms as “protectorate” and “suzerain power” smack of long-gone colonialism, which should have no place in modern systems of international relations. In the colonial treaties the British imposed on Bhutan, they promised not to interfere in Bhutan’s internal affairs but insisted that the country subject itself to British “guidance” in foreign affairs. When India won independence in 1947, it inherited from British India its territory and a “colonial legacy”. In 1949, India signed a friendship treaty with Bhutan, under which Bhutan must subject itself to Indian “guidance” in foreign affairs. India’s control was somewhat weakened over time thanks to Bhutan’s persistent efforts. But it remains a formidable barrier insofar as Bhutan’s desire to establish diplomatic relations and sign a boundary treaty with China is concerned. In fact, India and Bhutan are the only two countries that still have outstanding territorial disputes on land with China. By invoking such obsolete colonialist concepts as suzerainty to support its argument in the 21st century world where sovereign equality of all countries is the order of the day, India is obviously on the wrong side of history. Worse still, by showing no respect for Bhutan’s independence, India poses a direct challenge to the current system of international relations.

To sum up, India’s attempts to justify its illegal and unlawful trespassing of China’s Donglang area are totally untenable, reflecting an unfortunate tendency on the part of India to pursue its own interests without giving due consideration to those of others and showing no respect for others’ independence and sovereignty. Ever since the standoff started, China has displayed maximum goodwill and restraint out of consideration for the greater interests of China-India relations. India, instead of reciprocating China’s goodwill, has chosen to stick to its unlawful course. India should not underestimate China’s determination and capability to safeguard its sovereignty and territorial integrity, or it will face unpleasant consequences.