Methane hydrates are a form of compressed natural gas that lay on the sea bottom. Developing them is risky and costly. Despite this, methane hydrates are an abundant fossil fuel resource that could last decades – if not centuries. For China, which now sees getting access to sufficient energy as a critical national challenge, this matters.

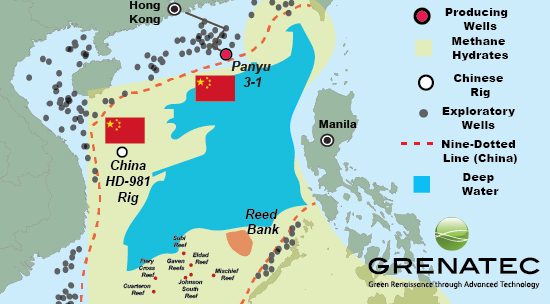

In addition to potentially large resources of oil and gas, the South China Sea’s deeper waters also are believed rich in methane hydrates.

Source: US EIA, Klaudia & Sandler, 2005

Estimates of the South China Sea’s methane hydrate potential now range as high as 150 billion cubic meters of natural gas equivalent. That’s sufficient to satisfy China’s entire equivalent oil consumption for 50 years.

Southeast of Hong Kong, China’s offshore Lingshui 17-2 field shows signs that – all by itself – it could hold 100 billion cubic meters of natural gas equivalent. Given this, China may be trying to gauge the extent of methane hydrate deposits elsewhere in the South China Sea. This could explain China’s placement of an oil and gas rig off Vietnam twice in the past year. Both locations, lying between North Vietnam and the Paracel Islands, are considered promising places to look for methane hydrates.

In addition to offshore China and northern Vietnam, the Reed Bank area located west of the Philippine island of Palawan may be another South China Sea methane hydrate honey pot.

The Sampaguita Field within Reed Bank may also hold large deposits of natural gas equivalents in the form of methane hydrates, according to Philippine estimates.

Coincidentally, some of China’s current South China Sea reef reclamation efforts are occurring on Mischief Reef and Nansha Island. Both of these are located just south of Reed Bank.

Both Mischief Reef and Nansha Island would be ideal for servicing and providing military security for offshore methane hydrate development in Reed Bank.

For years now, China’s has been investing heavily in offshore oil production technology. China plans begin testing offshore methane hydrates extraction technology in 2017. China plans to begin commercial exploitation of methane hydrates by 2030 – without saying where.

As it happens, methane hydrate resources also exist in territorial contested areas of the East China Sea. China recently resumed exploration drilling in an area just west of a bilaterally recognized maritime equidistance line separating China and Japan. In 2008, China and Japan both paid lip service to potential joint development in the area.

Separately, in offshore areas north of Taiwan, the disputed Senkaku Islands may also hold commercial amounts of methane hydrates. To date, however, no exploration activity has occurred there that’s been publicly announced.

Extracting methane hydrates is expensive, technologically-challenging and time-consuming. Developing the resource will require political stability. And that will require either a lot of gunboats or a lot of diplomacy.

At present, however, China’s saber rattling over its expansive, unilateral claim to virtually the entire South China Sea is now driving the Philippines and Vietnam closer to a bilateral strategic partnership, one that might later be expanded to include Japan.

At best, this will complicate any Chinese plans to unilaterally develop methane hydrates in disputed South China Sea waters. The reason is that doing so will almost certainly require an overwhelming show of Chinese maritime force to ensure security for its exploration and production efforts. This will raise the political and economic costs involved in developing methane hydrates. At worst, it could lead to a 1964 Tonkin Gulf-type incident at sea that leads to war. China’s unlikely to want that.

Far better would be for China to deploy its sophisticated technology backed by the deep pockets of its Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank to create ‘partnerships’ with the Philippines and Vietnam to develop these offshore resources. Indeed, China has often held up the idea of ‘joint development’ in the South China Sea.

For years now, Philippines exploration company Philex has been negotiating with China along these lines over Reed Bank.

Separately, China and Vietnam have agreed to jointly explore for oil and gas together on either side of their mutually recognized maritime equidistance line separating North Vietnam from Hainan Island. Both sides also have paid lip service to the concept of joint development in the South China Sea.

Progress in this direction, however, is hampered by China’s increasingly strident statements of its ‘indisputable’ claim to virtually the entire South China Sea.

One way for China to restore the eroding trust this is causing among its South China Sea neighbors is to create Joint Development Areas for development of methane hydrates.

Joint Development Areas exist all over the world. Two exist in the Gulf of Thailand. They are commonly used by disputing nations to freeze disputes indefinitely over offshore areas while they jointly develop the resources within them.

The economic and political logic behind Joint Development Areas is that they postpone final decisions on disputed sovereignty until far in the future when the stakes are lower because the resources have been developed. At this point, it’s worth pointing out developing methane hydrates may ultimately prove either technologically-impossible or economically-unviable. The reason is that methane is a very powerful greenhouse gas. It has emissions many times that of coal.

As a result, even with the best technology, the methane emissions released from developing deep-sea methane hydrates, if subject to carbon costs, may render investment in the resource uneconomic. What this means is that a policy of unilateral territorial assertion of sovereignty over South China Sea areas with methane hydrates may not make sense on either economic, military or diplomatic grounds.

That’s because developing methane hydrates may create large greenhouse gas costs, large military outlays to ensure security in disputed waters and/or create large diplomatic fallout hindering Chinese cooperation with her southern neighbors in other areas.

Given the above, creating Joint Development Areas with the Philippines and Vietnam seems a more sensible outcome. It can also set an attractive precedent for resolving other issues in the South China Sea, such as fisheries, rights of transit, people smuggling and humanitarian relief. China has citied these reasons as motives for its construction of military-style infrastructure on strategically located but contested islands. These include Mischief Reef, Gaven Reef, Hughes Reef, Subi Reef, Fiery Cross Reef, Johnson Reef, and Cuarteron Reef.

The lack of credibility with which these claims have been received in the international community has led the United States to hint it may engage in maneuvers near disputed islands to demonstrate the principle of ‘free passage’ – which China supports. China also potentially faces an adverse ruling by a UN-panel next year on the Philippines claim. If this were to occur, it will put more political pressure on China to make its intent in the South China Sea clearer.

Negotiating with neighbors on Joint Development Areas would create a win-win outcome, and defuse what may escalate rapidly into a regional diplomatic crisis.