Last week, I had a three-hour chat with an international student from North Korea, which was my first substantial conversation with anyone from that country, and ultimately, very surprising. In order to protect this student’s identity, he asked that I do not use his name for this piece. As an undergraduate student studying in China, he began by introducing his personal experience starting in kindergarten, namely how he experienced a kind of Soviet Union style education system: tuition free, 5-score rather than 100-score grading system, four “revolutionary-thoughts” courses, and most significantly, a long period of military training.

I then asked about his attitude toward China and the China-DPRK/Korean Peninsula relations. In China’s history textbooks, China and the Korean peninsula were friends for thousands of years. Confucianism and Buddhism spread from China to the Peninsula. China helped the Korean Peninsula counter Japanese invasion on three separate occasions, and most recently, China and the DPRK fought the American-led United Nations’ troops, side by side. In short, both nations have been good friends—and even allies—for centuries.

Yet this particular student seemed uninterested in the “good old days.” Instead, he felt more comfortable discussing China’s invasion of the Korean Peninsula and how their heroes defeated the Chinese troops. Moreover, he talked a lot about the Goguryeo dispute and the Changbai Mountain issue.

China claimed the Goguryeo Empire as a regional regime that originated in Northeast China, whereas both North and South Korea regard it as a long-lasting and powerful dynasty of the Koreans. The Goguryeo controversy has hovered over the China-Korean Peninsula relations for years, and it seems like there is no easy resolution in the foreseeable future. He further explained that there is a prominent narrative in North Korea that believes the DPRK should renegotiate the border with China to get back the Changbai Mountain (长白山), or Baekdu Mountain (백두산) in Korean, which is a sacred symbol of the DPRK regime. In February 2007, a group of South Korea’s speed-skating athletes posted a hand-written and provocative slogan—“Baekdu Mountain belongs to us”—in Changchun, Jilin Province, China.

He also implied that there’s even a call for reclaiming—if possible—the territorial sovereignty over the Jiandao islands (间岛), or Gando islands (간도) in Korean. The so-called “Jiandao” or “Gando” is a large geographic area controlled both by China and Russia. Even as a student of international relations, I fully admit that I have never heard of this seemingly obsolete sovereignty issue. And yet while North Korea and South Korea are different governments, they share a very similar reading of history and territorial controversy.

He became more talkative when the topic turned to the nuclear issue and U.S.-DPRK relations. As he described, Koreans have never enjoyed true independence. China, Japan, Russia and America invaded the Korean Peninsula, one after another. China imposed the tributary system upon Koreans until the early 20th century; Japan annexed and colonized it for about half century; and most recently, Russia and the U.S. divided Korea into two parts. Such a miserable history now compels Koreans to fight for real freedom and independence. Culturally, however, Sejong the Great invented the native script system around 1446 named the Hunminjeongeum (训民正音). In terms of culture, therefore, Koreans had already achieved independence.

Unfortunately, Koreans still have not achieved complete political independence. Given the Korean Peninsula’s geopolitics—which is greatly affected by its location between major powers—the use of nuclear weapons, he believes, is the only way to achieve that ultimate end. During the Cold War era, North Korea was under the nuclear umbrella of the Soviet Union and China; there was no urgent incentive for North Korea to develop its own nuclear weapons. Shortly after the end of the Cold War, however, the former Soviet Union’s security guarantee over North Korea disappeared. Even worse, China, the DPRK’s most important security guarantor, established formal diplomatic relations with South Korea in August 1992. Hence, the balance of power in the Korean Peninsula was broken up unilaterally. Facing the threat from South Korea and the U.S. alone, North Korea started its journey to obtaining nuclear weapons.

In January 2002, President George W. Bush, in his first State of the Union address, labeled North Korea as a member of the so-called “axis of evil,” which also included Iraq and Iran. The United States then invaded Iraq and hung Saddam Hussein publicly. For North Korea, the Iraq War meant that Bush’s “axis of evil” might be a declaration of war and not merely intimidation tactics. Undoubtedly, Bush’s concept caused a furor in North Korea. In frustration, my interlocutor exclaimed, “You know, America is a super power which has the most powerful military—ballistic missiles, aircraft carrier fleets, fighter jets, and tens of thousands of soldiers deployed in South Korea and Japan’s bases. Their president just labeled our country very negatively. You can only imagine our feeling knowing this!”

Recently, in the cases of Libya and Ukraine, the former gave up its nuclear program under the pressure of the United States, and the latter abandoned its nuclear arsenal with security guarantee from the U.S., the UK, and Russia. To this student, it showed once again that it is in Korea’s best interest to keep their nuclear program. “Once you abandon nuclear weapons, no other country or security guarantee can be trusted in the case of a crisis.”

Kim Jong-un’s strategy is not so different. It’s certain that Kim understands how far behind North Korea has been left by the rest of the world. Moreover, he understands that the regime may be in danger if the country continues to suffer economic stagnation. Undoubtedly, the economy will not be on the right track as long as the DPRK’s security is under pressure. Kim’s strategy therefore is quite straightforward—obtain the nuclear weapon first to allow for a more balanced international environment, then open up the country to develop the economy. In other words, the economy is the end, while the nuke is just the means to that end.

This strategy is nothing new for the world, namely the so-called “Military First Policy”—or Songun Chongch’I. But just like President Bush addressed, “North Korea is a regime arming with missiles and weapons of mass destruction, while starving its citizens.” For President Bush, the “Military First Policy” means that missiles and WMD are all that matters—citizens be damned. Also in this mindset is an ideological paranoia which deliberately disregards North Korea’s own logic for the policy.

Understandably, given the huge communication deficit between North Korea and the rest of the world, it is difficult to observe North Korea neutrally. Similar to the skeptical observers in the West, many Chinese people also perceive North Korea with bias. Kim Jong-un’s “fat pants,” the bizarre military parade and all kinds of political rumors (one more salacious one being that Jang Song Thaek, Kim Jong-un’s uncle-in-law and former Vice Chairman of the National Defense Commission, was executed by 120 ravenous dogs) are going viral in China’s social media.

It is little wonder that most Chinese people are concerned about the Korean Peninsula crisis. And due to the continuous deterioration of DPRK-China relations, Chinese people’s attitude towards North Korea continues to deteriorate. People from Northeast China especially loathe the DPRK. One friend from northeast China anonymously told me, “I hope the DPRK will not collapse, otherwise millions of refugees will flood to our hometown. That’s would be a disaster. Our economy definitely will collapse and society will descend into chaos immediately.” Additionally, more and more Chinese intellectuals claim that North Korea has already become a trouble-maker and cannot rely on China to be its buffer zone anymore. Chinese critics have appealed to the Chinese government to “abandon North Korea” as soon as possible. Increasingly, this kind of public opinion pushes China’s foreign policy in the direction of Koreanophobia.

Meanwhile, western nations have pressed China to “control” North Korea for years. When I was attending the Five-University Conference on East Asian Security in Tokyo (featuring Princeton University, Peking University, University of Tokyo, Korea University and National University of Singapore), Professor Thomas J. Christensen from Princeton University repeatedly criticized the Chinese government for failing to step-up and pressure the DPRK. Similarly, at this year’s Munich Security Conference, a western journalist asked Fu Ying, China’s former Vice Foreign Affairs Minister and current Chairwoman of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the National People's Congress, why China could not “control” North Korea. In short, for the United States and some Western countries, only China has leverage over North Korea. Therefore, China should join with the West to sanction and press North Korea until it completely concedes and joins the negotiation table.

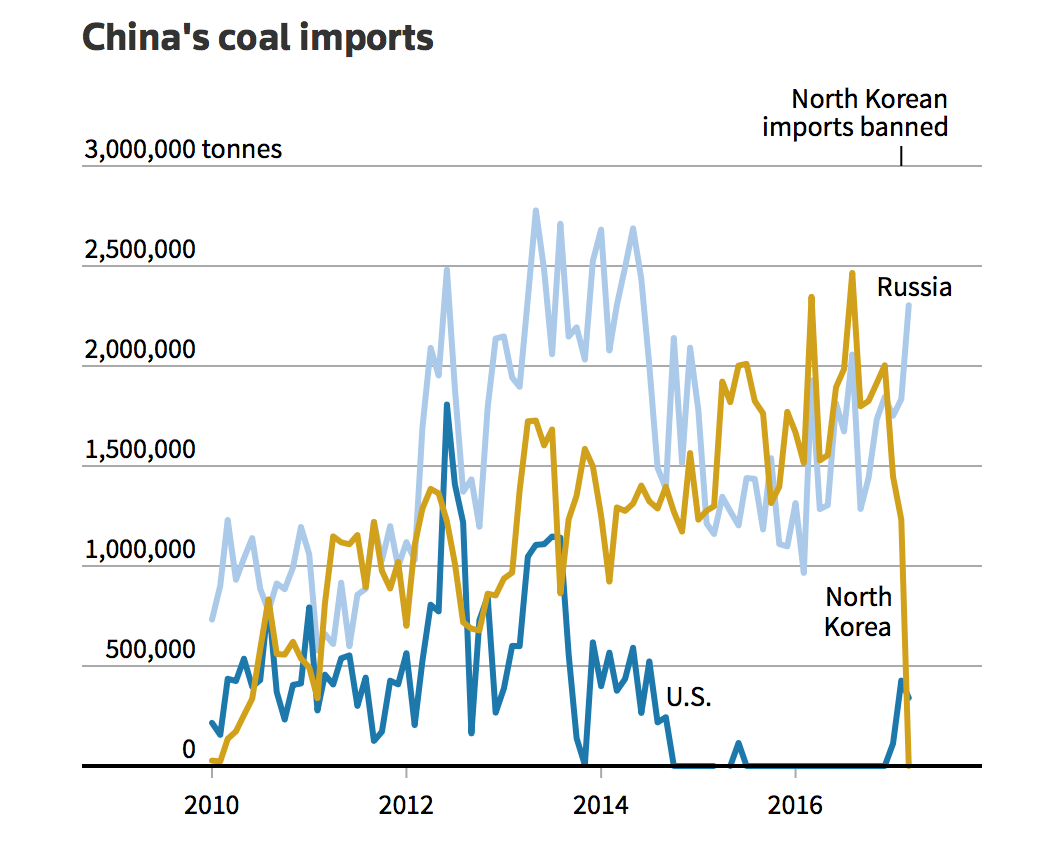

To some extent, domestic public opinion and America’s pressure have recently taken effect. According to Reuters, China bought nearly 70 percent of North Korea’s exports, most of which were coal, metals, and other raw materials. On February 26 this year, China finally banned its coal imports from North Korea. Additionally, some sort of anti-DPRK news reports have gradually become a “new normal” for Chinese mass media. Global Times, a mainstream and nationalistic newspaper repeatedly publishes articles to condemn North Korea’ arrogance and irrationality.

Figure 1 China’s coal imports since 2010

Source: China’s grip on North Korea’s economy. (2017, May 4). Retrieved May 8, 2017, from Reuters.

Immediately and fiercely, the Korean Central News Agency (KCNA), the official news agency of the DPRK, responded with a commentary article on May 3rd. In this commentary, the author—on behalf of the DPRK government—asserted that China’s “reckless words and deeds undermining the DPRK-China relations must be stopped,” and that, “it was never China but just the DPRK whose strategic interests have been repeatedly violated due to insincerity and betrayal on the part of its partner.” KCNA’s commentary caused uproar in China’s mass media. Consequentially in China, anti-DPRK commentaries continue to grow as public opinion becomes increasingly Koreanophobic.

For America and some Chinese public intellectuals, it seems like good news. Since the deterioration of China-DPRK relations, the DPRK has been more isolated while China, South Korea and America now reside in the same boat. The game of the Korean Peninsula was 2:2 previously. Now, it should be 3:1. Is this true? According to my basic knowledge of international relations theories and my chat with this North Korean, I would say it is not.

First, North Korea’s deeds and belligerent rhetoric are defensive rather than offensive. Due to the Soviet Union’s collapse and the establishment of the China-South Korea diplomatic relations, North Korea lost its reliable nuclear umbrella. Thus, after the end of the Cold War, North Korea started its own nuclear program. In other words, North Korea just wants to develop its own nuclear umbrella and stand on its own two feet. The most important incentive here, certainly, is self-defense. And it is clear that North Korea will continue to develop its nuclear program until it feels safe.

Second, sanctions and military pressure will make things worse rather than resolve the problem. America and its allies’ long-lasting sanction has made North Korea’s economic situation worse, while there is no evidence that North Korea’s economy will collapse anytime soon. The bitter truth is we have seen annual joint military drills between the United States and South Korea during the past decade along with an increase in North Korea’s nuclear and missile tests.

Why did North Korea choose not to yield to the external pressure and instead become more belligerent? Compared with Iraq and Libya, North Korea has a larger population, a stronger military, and a propaganda system of propaganda. I asked the North Korean student a tricky question during the end of our chat: “North Korea’s repeated nuclear and missiles tests seem to have already provoked both China and America. What will you do if war were to come to the Korean Peninsula?” He immediately responded, “No doubt, I’ll drop out [from university] immediately and enroll into the People's Army! There’s no other choice, and besides, we’ve become accustomed to wars. War is not such horrific stuff.”

As a prospective “elite” of North Korea, whether as a result of propaganda or heartfelt patriotism, this boy spoke this sentence loudly without any hesitation. In view of this, it appears that North Korea is much more resolved than we thought.

Most importantly, North Korea borders on South Korea, America’s security ally. Pyongyang and Seoul are just dozens of miles away from each other. In the case of military conflict, Seoul, along with the entire South Korean nation, will be under attack. It’s apparent that both South Korea and the United States cannot afford this kind of threat.

And as previously mentioned, North Korea has taken several nuclear tests and claimed itself a nuclear power. Presently it remains unclear whether or not this is true. But it is certain that North Korea is much closer to the nuclear threshold today than it was no more than a decade ago. Evidently, there’s not much time left. Both China and America should try to solve this problem before it’s too late, otherwise there would be only one choice—recognize North Korea as a nuclear power in the near future.

So how can China and America address the Korean Peninsula crisis? It’s straightforward: make North Korea feel safe. For China, the country needs to continue to convince North Korea to pause, and even stop, its ongoing nuclear program, and more importantly, China should persuade the U.S. to adapt to a more pragmatic and feasible approach to address the crisis. As for the United States, North Korea’s nuclear stability relies on fewer joint military drills along with reduced intimidation and ideological paranoia. It is increasingly apparent that North Korea’s desire for national security determines its nuclear interests, thus China and the United States must reduce military aggression and economic sanctions in order to increase stability.