The Geo-Economics Battle

The race of geopolitical strategies based on infrastructural development abroad is a part of the new great powers rivalry. The so-called geo-economics contest (Luttwak) is the new global battle, a competition through commerce for getting economic advantages at the intersection of investments and loans, contracts opportunities, conquest of more worldwide market share and improvement of own supply chains, with the declared noble aim of contributing to global development.

Nevertheless, it visibly goes farther than that: as Medcalf has stated, “nations are now competing for advantages through economics rather than, or, more precisely, in addition to, military force”. Actually, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has proved that China leverages the investments to promote its multiple strategic interests globally and to influence.

The U.S. and the EU Enter the Contest

The U.S. published in June 12, 2021 the Build Back Better World (B3W) strategy, launched together with other leaders at the 46th G7 summit “to discuss strategic competition with China”[1].

Three months after, on September 15, 2021, the President of the European Commission gave an important speech, remarkably disclosing a new connectivity strategy labelled the Global Gateway, finally approved on December 1, 2021. Ursula Von der Leyen advertised the new intentions to compete and counterweight the foremost Chinese project:

“It does not make sense for Europe to build a perfect road between a Chinese-owned copper mine and a Chinese-owned harbor. We have to get smarter… We want to create links and not dependencies!”, she determinedly targeted at the State of the Union Address[2].

Therefore, both the U.S. and EU scale-up infrastructure ventures have unambiguously declared their alternative to the BRI, almost ten years after the latter started. These challenges inevitably force a comparative analysis.

Big Differences in the Packages

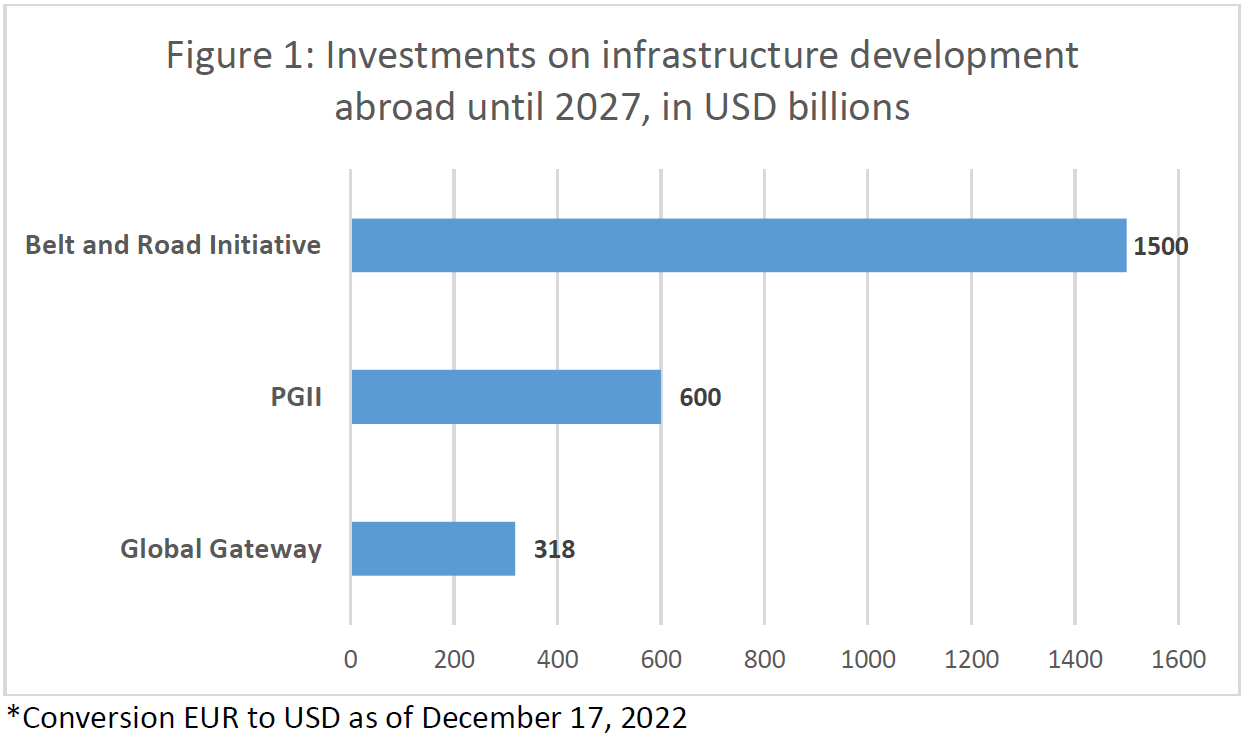

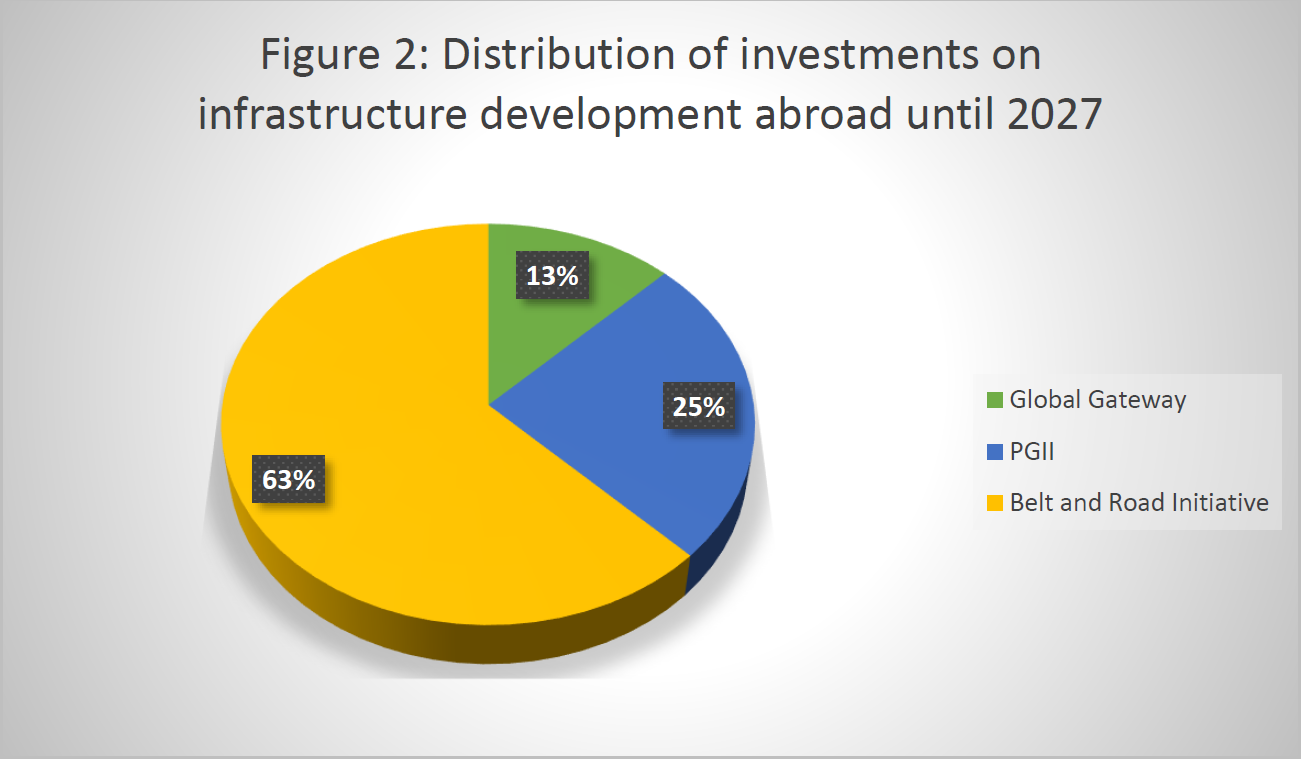

The Global Gateway is a rebranding of the EU’s Global Strategy (2016) and the Connecting Europe and Asia - Building blocks for an EU Strategy (2018), becoming one of the hugest domestic undertakings ever, and “mobilizing” up to 300 billion EUR by 2027 with public and private funds, in an attempt to reinforce economic resilience.

To draw the comparison, the U.S. declared then that the B3W “will collectively catalyze hundreds of billions of dollars in the coming years”. It changed the denomination to Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment[3] (PGII) on June 26, 2022, one year after the first announcement, fixing finally the time duration, up to 2027, and the total funds in 600 billion USD. One third of them would be the U.S. contribution (200 billion USD). The rest is supposed to be funded by the other G7 members, where three EU Member States belong as well: Germany, France and Italy (the EU joins as a “non-enumerated member”).

China, instead, has been able to supply the BRI with over a trillion USD[4] in the span of ten years, intending to endure the effort and, even more, promising to fund over 100 billion USD per year from now on, which would increase the investments up to a total of 1.5 trillion USD by 2027.

Yet, in order to have the full picture, it should be noted that the EU and Member States together have been so far “the world’s leading providers of official development assistance”, including China and the U.S., according to a report published by the European think tank Bruegel[5].

Going Slower than Projected

After the high expectations expressed by the U.S. and the EU, it is enigmatic why there has not been much information about their flagship strategies since both were launched. Yet, it can be found out.

In fact, the first meeting of the Global Gateway Board took place on December 11, 2022, more than one year after its pronouncement. It did not catch much public scrutiny. According to the official declaration, “it identified operational priorities for working together in 2023 to roll out Global Gateway with partners”.

Global Gateway: 5.5% Invested During 16.7% of the Time Projected

With one sixth of the time for the completion of the project already vanished, in an ambiguous EU press release[6] (the actual data is not listed on any public site, an unusual lack of transparency within an international organization used to disclose information real time), the declared amount invested so far is of 9 billion EUR in grants, and 7.4 billion EUR under the EFSD+ guarantee agreement signed in May 2022 with the European Investment Bank: a mere 5.5% of the overall amount compromised.

In other words, when 16.7% of the time projected for completing the Global Gateway has already run out, the quantity financed is of 5.5%, unexpectedly low, moreover when the War in Ukraine has provoked extremely urgent needs in matters such as energy consumption and sourcing, and the EU could use the Global Gateway for guaranteeing further supply and reasonable prices.

Despite those figures, Von der Leyen defined again the Global Gateway as a “geopolitical project”, “a critical tool”, with “key investment to boost digital connectivity through underwater data cable and terrestrial connections between the EU and its partners, to increase energy renewable production with investments in solar plants and wind farms and to increase access and manufacturing capacity of vaccines, medicines and health technologies”.

Lack of EU Political Direction

The EU institutions declared that the Global Gateway strategy “is firmly under way”. Conversely, to some extent, there seems to be a lack of political direction, if we consider the real compromise, the figures, the process, and the declarations by the parties involved. Surprisingly, an official document with Q&A released by the Commission questioned itself if the Global Gateway “was a response to the Chinese BRI”, without providing the direct answer that would be required, and mentioning instead the U.S. and its then B3W strategy to “mutually reinforce each other”[7].

More bizarrely, top EU diplomat Josep Borrell evaluated the first Global Gateway anniversary linking it to the fight against disinformation and the protection of the liberal order: “If we want to protect the rules-based multilateral system, we have to make Global Gateway a success”. The EU leaders actually missed a great opportunity for assessing how the first year investments have meaningfully impacted the governance in the recipient partner-countries involved.

Last, unfortunately, the Global Gateway only gained European attention when the Commission hosted last November for promoting the initiative a 387,000 EUR gathering in the metaverse, said to be attended by five people. The Commission peculiarly dared to dispute that figure, assuring that in fact up to 300 people joined the party[8] (if we take it for granted, every attendant cost 1,300 EUR), animated by house music and the attractiveness of a presumed tropical island, a surprising setting for the promotion of what is supposed to be a strategic project.

BRI is Spread All around the World, Including Europe

The BRI is said to have been joined by around 150 countries so far. As a matter of fact, China has been able to sign as well Memoranda of Understanding with fifteen EU Member States (including some of the most powerful ones, such as Italy), who were bypassing the EU institutions, something that it is forbidden by the internal rules. Furthermore, China is involving in the BRI EU candidate countries in the Balkans, unsettling their applications, and it has been able to achieve investments in the busier European strategic infrastructures, such as the Piraeus port in Greece, and the recent stake bought of the Hamburg port in Germany.

The Timeless Question: Partners, Competitors or Rivals?

The EU defined China in 2019 as a “negotiating partner, economic competitor and systemic rival”. The Global Gateway should be encompassed within the “competitor” assertion, but its progress makes one wonder whether the European leaders are meeting their goals in terms of global competition and infrastructure expansion abroad. One year after the takeoff, it has not had the required visibility. Was the Global Gateway designed too ambitiously, considering the current endeavors? Has been the shift from development aid to strategic investments successful so far?

The EU should prove that the Global Gateway is the right step forward, and, if it is not, modify the strategy. 2022 has been particularly challenging for Europe, as many circumstances and policies have changed since February 24, the day the Russian Federation invaded Ukraine. Budgets and priorities have changed in the Member States and the EU, therefore, also the Global Gateway should be adjusted accordingly.

There is indeed a long way for the EU ‘Silk Road’ to compete globally with China on infrastructure development. In addition, the EU requires to focus more accurately, design credible projects, and adapt more rapidly to geopolitical changes. In any case, it has started an indispensable self-reflection to become more influential. It should keep using trade as a geopolitical tool, leveraging economic interest into statecraft opportunities. Realpolitik is the only way for becoming an influential long-term geopolitical power.

[1] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/06/12/fact-sheet-president-biden-and-g7-leaders-launch-build-back-better-world-b3w-partnership/