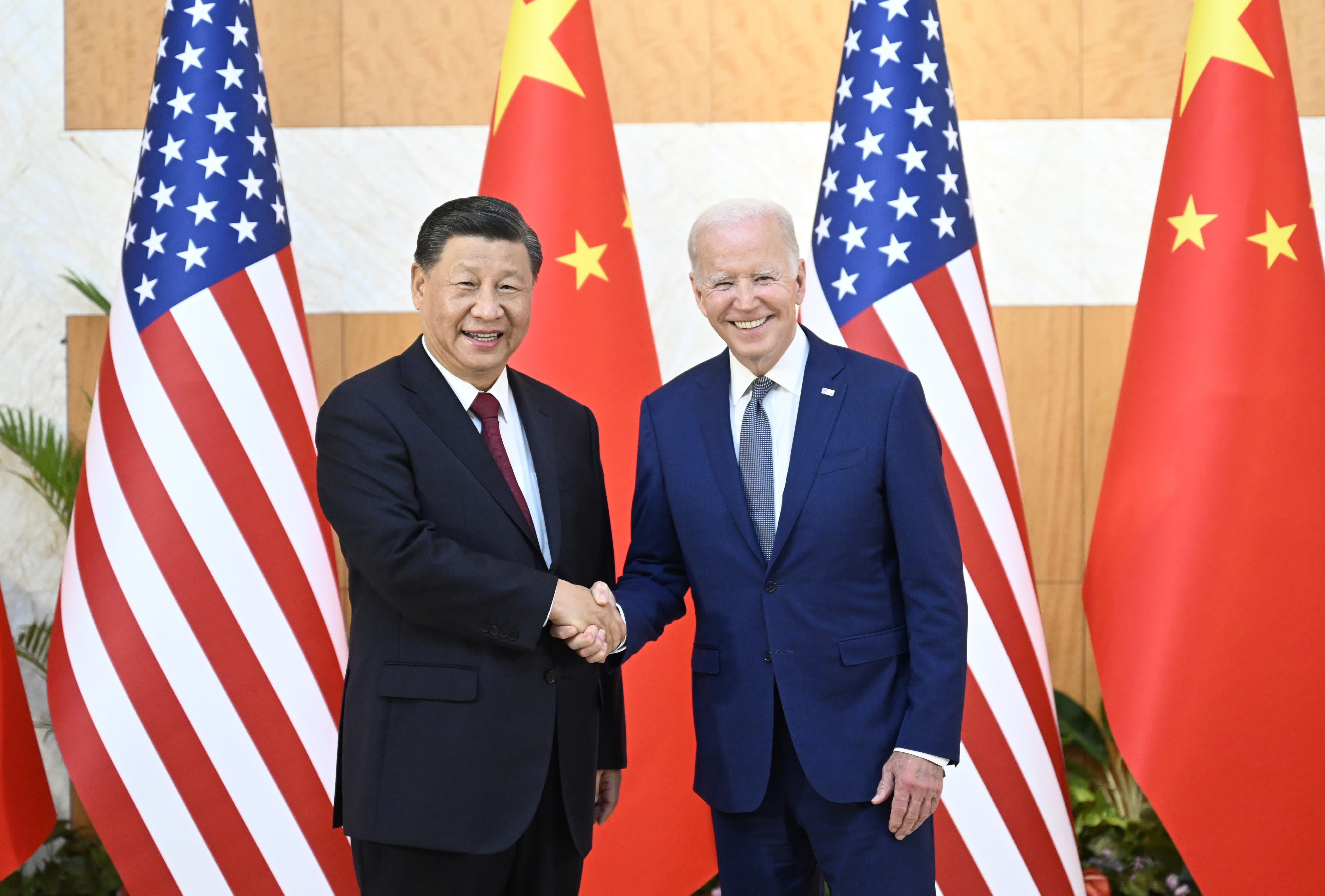

Chinese President Xi Jinping and U.S. President Joe Biden talked on the sidelines of the G20 summit on Nov. 14 in Bali, Indonesia — their first face-to-face meeting since Biden’s election. Although the two had maintained communication via telephone, letters and video links, the in-persons meeting was irreplaceable. When the two smiling leaders shook hands, the message to the world was that for all the differences and competition between China and the U.S., they are not irreconcilable enemies.

Their meeting was candid, in-depth and constructive, as the two sides exchanged ideas about bilateral relations and regional and international concerns. China-U.S. relations have been interest-driven since Richard Nixon’s China visit. Defining and affirming common interests has been the foundation. In different periods of history, thanks to changes in international and domestic conditions in both countries, common interests have changed; confirming them, therefore, is a dynamic process.

President Xi systematically expounded the three layers of interests shared by China and the U.S. — a common interest in no conflict, no confrontation, with peaceful co-existence at the most basic level; common interests in the two economies’ deep integration, interdependence and the benefits of each other’s development; and common interests in coordination and cooperation in the post-pandemic world’s economic recovery, coping with climate change and resolving regional hot spot issues. The arguments are based on in-depth analyses of bilateral relations and international conditions and thus should form the foundation of China-U.S. relations in the decades to come.

Since Biden entered the White House, he has kept a certain distance from his predecessor in some aspects of China policy, such as resuming contact between heads of state and maintaining high-level strategic communication; no longer pestering China on tracing the source of the coronavirus; Meng Wanzhou’s return to China; collaborating on climate change responses; partially restoring people-to-people exchanges; and the U.S. side committing to the “five Nos,” especially promising to not seek to change China’s system or challenge the ruling status of the Communist Party of China.

During the Donald Trump presidency, the U.S. side directly targeted the CPC, sparing no effort to smear China’s political system. In June and July 2020, the Trump administration’s national security adviser, FBI director, attorney general and secretary of state all delivered diatribes directly attacking China’s political system and CPC leadership with greater frequency and with forcefulness than U.S. attacks against the former Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War.

President Xi attached great importance to the U.S. commitment to the “five Nos,” while pointing out a major problem in America's China policy — “saying one thing and doing another.” Over the past two years, the Biden administration’s China policy has remained on the same track that was laid by the previous administration in many respects, especially on three central issues.

First is Taiwan, which is the core of all core Chinese interests and the basis of China-U.S. relations. For two years, the U.S. side has continued hollowing out the “one-China” principle, building substantial relations with Taiwan, including military exchanges and arms sales, attempting to integrate Taiwan’s advantages in high-tech chip manufacturing into the U.S. strategic industry chain, while suppressing companies on the Chinese mainland. Multiple members of Congress visiting Taiwan, the most damaging of which was House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit in early August, which dealt a serious blow to the “one China” principle and lent support to separatists on the island.

Second is that the U.S. doubled down on its so-called Indo-Pacific Strategy, emphasizing the idea of shaping the environment around China, enhancing and building various forms of alliances and partnerships on China’s periphery, launching the IPEF to counter the RCEP and increasing input in the South Pacific in an attempt to contain China.

Another issue is the suppression of China in the high-technology sector. The U.S. has engaged in the tactic of “small yard, high walls,” repeatedly mounting sanctions against Chinese companies, especially in chip manufacturing. It has conducted a form of decoupling and suppression, even hurting American high-tech companies and causing unspeakable pain for U.S. allies.

One concept was repeated three times, with slightly different wording, in the U.S. National Security Strategy Report published in October: The PRC is the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to advance that objective. The U.S. thus has identified China as its most important geopolitical competitor in the long run.

This is America's biggest strategic misjudgment about China. During his meeting with Biden in Bali, President Xi said frankly that China has never sought to change the existing international order or interfere with U.S. domestic affairs, and it has no intention to challenge or replace the U.S. This is ultimate honesty delivered to the U.S. side. If the latter insists on taking China as its biggest strategic competitor, it will continue escalating tensions, even turning that misjudgment into a self-fulfilling prophecy that would be no blessing — to China, the U.S. or the world. This is why China refuses to define China-U.S. relations through the lens of competition.

During the meeting, the two leaders reached consensus on a series of points regarding a relationship of no conflict, no confrontation and peaceful co-existence. Secretary of State Antony Blinken will visit China soon, and working teams on both sides will then follow up and take practical steps to implement the important ideas the leaders worked outd, explore guiding principles — that is, the strategic framework — for bilateral ties, so as to manage and stabilize the relationship.

Having passed through decades with many twists and turns in bilateral relations, we certainly won’t have unrealistic fantasies or expect that everything will be fine thereafter. The relationship may never be free of divergences, competition and struggles. However, as long as both sides take the common ground found in the meeting as a compass, they will be able to find a correct way of getting along. They can make bilateral ties continue to work to the benefit of both countries and the world.