As China-U.S. relations remain strained and multi-directional diplomacy gains momentum, the importance of positive relations with Germany and Europe has grown in China’s broader diplomatic landscape.

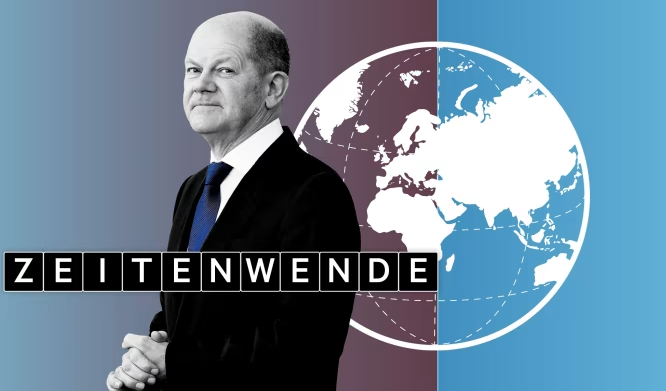

This economic partnership was a cornerstone of China-Germany relations during the Merkel era. In the post-Merkel era, relations are undergoing a shift in perceptions and interests. Germany’s policy on China has undergone reconstruction within what it calls a “Zeitenwende” or historic turning point.

After the outbreak of the Ukraine war early last year, Chancellor Olaf Scholz, Merkel’s successor, cited it as a watershed moment in Europe’s history. He emphasized in a speech that Feb. 24, 2022, “marks a watershed in the history of our continent.” Since then, “Zeitenwende” has become a guiding term across various policy domains.

Two years later, as interpreted by the German government, “Zeitenwende” carries several connotations:

• First, the post-Cold War era that blessed Germany and Europe is ending in a turbulent transition before the dawn of a new era.

• Second, Germany was too naive in its prediction of threats from Russia and overestimated its malleability. Now that geopolitics in Europe has deteriorated across the board, Germany once again stands at the forefront of the strategic game where it must balance security against economic growth.

• Third, the world is shifting toward a multipolar reality as the U.S. loses global control. A Europe that fails to strengthen itself risks marginalization.

• Fourth, Germany rejects the idea of a return to a two-camp world.

• Fifth, Germany faces challenges in generating economic growth, necessitating reforms across the country and in the European Union.

Under the notion of “Zeitenwende,” Germany is readjusting in all aspects at home and abroad. It has strengthened its national security policies to compensate for insufficient investment during the Merkel that weakened its defense capabilities. It openly supported Ukraine in resisting Russia with “no hesitation,” believing it had no choice. And it actively lobbied Europe and the U.S. to unite and do more.

Economically, Germany broke the balanced budget rule as it invested in renewable energy, and increased its investment in information technology, business development and infrastructure. Socially, Germany implemented new immigration policies and further relaxed restrictions on immigrant professionals.

In fiscal 2024, Germany’s defense budget reached a historic $73.41 billion, a notable surge from the 1.57 percent level recorded in 2023. This increase aligns Germany with the NATO benchmark, which mandates that member states allocate a minimum of 2 percent of their GDP for defense expenditures. During the 60th Munich Security Conference, Boris Pistorius, the German defense minister, announced the potential for further escalation, with the country considering ramping up its military spending to as much as 3.5 percent of its GDP.

Driven by security and economic factors, Germany has embraced a “de-risking” strategy, committing itself to activating the EU’s internal development and cooperation potential. The change in diplomacy also aims to strengthen its engagement in the Indo-Pacific Region and focus on winning support from the Global South.

Despite the “Zeitenwende,” Germany’s policy adjustments lack a distinctive new international image. Everything is still under development and needs deeper exploration.

The Munich Security Report 2024, which guided the annual conference, rarely reflected on the harm of the zero-sum mentality — a posture in which states’ increasing focus on relative gains instead of absolute gains could bring about a zero-sum world. The German strategic community has proposed how human society can break the “vicious circle,” reflecting that its thinking on the “Zeitenwende” keeps going deep and is now shifting from observing phenomena to exploring solutions.

In Germany’s “Zeitenwende,” China is an important, complex presence. In response to the rapid rise of China, Germany has aligned its foreign policy with the EU and positioned China as a “partner, competitor, and institutional rival.” The Munich Security Report 2024 identified China and Russia as the “main challenges” facing Europe and presented five categories of issues that concern Europe — geopolitical friction, economic uncertainty, climate change, technological competition and international cooperation — with some elaborations related to China taking up a substantial part and some chapters even directly beginning with the impact brought by China.

In proposing the concept of “Zeitenwende,” Germany suggests it has seen the importance of China’s rise. Berlin believes that in an increasingly multipolar world, the U.S. and China are its two most important poles, and their fledging strategic rivalry is an integral part of “Zeitenwende.”

Germany cannot afford to take sides — to choose between China and the U.S. It must remain on good terms with both. However, Germany still lacks faith and confidence in China’s policy direction and value system. It regards China as a corrector and challenger of the international order and flinches in the face of China’s traditional manufacturing industry, its new-energy industry and its technological innovation competitiveness. Hence the hype of supply chain, infrastructure and cross-border data security issues and the pivot to China in implementing the strategy of reducing dependence and “de-risking.”

The German policy toward China in the context of “Zeitenwende” exhibits a lack of clear guiding principles, as well as inconsistency across various fields, underscoring the intricate nature of Germany’s response to the complex implications of China’s ascendancy.

This policy orientation appears to be significantly influenced by U.S.-led Western public opinion, preventing a swift departure from its fundamental framework and establishing a distinct pattern.

In the Merkel era, Germany emphasized pragmatism over idealism. While aligning with the U.S. and NATO on security matters, Germany has simultaneously endeavored to reduce economic dependence on China and “de-risk.” This dual-track approach involves expanding business in China while fostering bilateral cooperation on global issues. However, practical implementation has proved challenging because of the impact of fragmented party politics inside Germany, resulting in local confusion and inherent contradictions.

Large German multinationals have responded whimsically to the government-proposed concept of “Zeitenwende.” They still aspire to increase market revenue and promote structural transformation amid economic globalization. They generally value the potential of the Chinese market and disagree with the excessive use of security implications when it comes to economic and trade issues. They do not view forced decoupling as wise or feasible. Nor do they exhibit optimism about reducing dependence, or “de-risking.” They hope that Berlin can maintain the fundamentals of economic and trade cooperation with Beijing.

Several German companies, such as BMW, Volkswagen, BASF and Siemens, reprogrammed their Chinese markets according to their respective global development strategies. In the process, they also capitulated to Berlin’s value concerns. Large German multinationals are also deeply concerned about China-U.S. tensions. They believe an increase in regulatory thresholds on both sides of the Pacific will pose challenges to normal business activities, and the increased costs will eventually be borne by consumers and thus inhibit corporate vitality.

Official statistics from German show that, despite a bilateral trade volume of 253 billion euros between Germany and China (Germany’s largest trading partner for the eighth consecutive year in 2023), the U.S. is catching up, with a record of 252.3 billion euros in trade with Germany. In 2023, the value of German imports from China fell by 19.2 percent to 155.7 billion euros, while the value of its exports to China fell by 8.8 percent to 97.3 billion euros. According to the German Macroeconomic Policy Institute, German companies have diversified their supply chains and reduced purchases from China; meanwhile, China has stepped up domestic production of strategic products and reduced German imports.

The latest report from the German Economic Institute, based on an analysis of data from Bundesbank, stated that Germany’s overall foreign direct investment in 2023 dropped from 170 billion euros in 2022 to 116 billion euros in 2023. However, direct investment in China maintained momentum, with an increase of 4.3 percent from the previous year in 2023 to 11.9 billion euros. It hit a new high, accounting for 10.3 percent of German foreign investment, the highest since 2014.

German companies’ investment in China in the past three years is equivalent to that of the previous six years combined. However, in the past four years, all German investments in China have been reinvestments after profits, with some withdrawals. A survey by AHK Greater China in January 2024 showed that the number of German companies that have withdrawn or are considering withdrawing from China account for 9 percent of the total, more than doubling the figure in the past four years.

China and Germany are both nation-states with profound traditions of philosophical speculation and a shared practice of outlining overarching strategic plans for the future. Talking about the German “Zeitenwende” in China inevitably reminds people of the assessment of “changes unseen in a century,” which have dominated China’s domestic and foreign policy adjustments over the past decade. The assessment of it is made with a global view, rather than being based on regionalism and localism, as with “Zeitenwende.”

However undeniably, there are some similarities, such as in the view of a multipolar world, insights into America’s weakening hegemonic control, support for the continuity of economic globalization and global supply chain integrity, calls for revitalizing multilateralism and strengthening global governance and advocacy for redefining the relationship between security and development. These shared opinions form the foundation for transcending differences and promoting cooperation.

The biggest difference between China and Germany as to viewing changes in the world is whether to pursue common security or collective security in protecting the world from camp antagonism, dealing with the vulnerability of the global supply chain by deepening cooperation and interdependence, pursuing reduced dependence and “de-risking,” handling value differences by calmly exploring the path to mutual respect and inclusiveness or attaching substantive sanctions for moral intervention. These differences can be bridged through candid and in-depth communication and, thus, through mutual understanding without profoundly affecting pragmatic cooperation between the two sides at the bilateral and global levels.

In the eyes of Beijing, Europe is an important pole in the future multipolar world, and Germany will always be the keystone underpinning Europe. How China and Germany reposition each other in a world undergoing tremendous change and establish a policy framework toward each other that adapts to the characteristics and requirements of the new era is a vision and wisdom test for leaders of the two countries and their citizens from all walks of life. A significant hurdle facing the China-Germany relationship is whether they can separate policy practices from their relations with third parties (or third-party policies) and achieve relatively independent development on route to securing freedom and enough room for a China-German partnership. It is the same case with China-EU relations.

The dichotomy of “changes unseen in a century” and “Zeitenwende” boils down to a critical question: What choices should a country make as humanity faces a historical transformation? The Chinese believe the answer lies in dismantling the pervasive zero-sum mindset through an unwavering commitment to win-win cooperation — hence, the proposal to build a community with a shared future for mankind.

This direction is what China expects in response to “changes unseen in a century.” In this shared vision, China and Germany, despite their distinct ideologies and security interests, have the potential to shape a future in which nations operate in harmony and foster a global environment characterized by cooperation, understanding and prosperity.