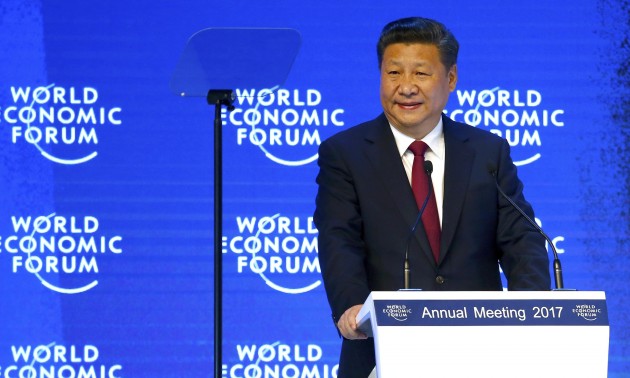

Chinese President Xi Jinping addressed World Economic Forum in Davos. (Reuters)

Immediately after the American President Donald Trump finished his first official visit to Beijing, China, the Chinese government made an announcement on November 10th: China will ease or lift investment restrictions on foreign companies in Chinese financial markets.

According to Xinhua, China’s leading state media outlet, Vice Finance Minister Zhu Guangyao announced this new policy during a press conference: “foreign business will be allowed to own as much as 51 percent of shares in a joint venture in securities, funds and futures industries” and “the cap will eventually be phased out in three years.” Since the previous cap was 49 percent for foreign business owners, the decision came as a big surprise for foreign investors. Morgan Stanley’s CEO Wei Sun Christianson expressed his excitement during an interview with Xinhua on December 8th: “the move is really great news for Morgan Stanley, which will allow us to get the management control and expand businesses. We are very anxious for the upcoming guidance and obviously we will apply.”

The decision was generally perceived as one of the many consensuses that China and America reached during the historical visit of President Trump to Beijing. It was also believed that the policy was a step further on the path to protecting and embracing globalization, which resonated well with President Xi Jinping’s speech at the Davos World Economic Forum earlier this year.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), China was the world’s fastest-growing major economy until 2015, with growth rates averaging 10 percent. Today, the growth rate in China no longer compares with what it was before. A Bloomberg report in 2017 concluded that: “China’s economy showed further signs of entering a second-half slowdown, as curbs on property, excess borrowing and industrial overcapacity began to bite.” With a significantly slowed-down economy, the real intention behind stimulating foreign investments has become more and more complex and ambiguous to foreign investors. Is the Chinese government aiming to achieve a win-win situation with foreign investors, or is it simply trying to use foreign investments as a tool to boost the domestic economy, and eventually create a protective, exclusive and competition-free environment for Chinese enterprises to grow in certain industries (such as resources and technology)?

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) was introduced to China in the 1978 Economic Reform. It was largely encouraged in China during that time not only because it contributed to the recovery of the economy, but also because it set paradigms and provided experience for a lot of Chinese enterprises. When China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, it agreed to adhere to treat foreign goods and services as equal as those produced domestically, which was also known as “national treatment.” But a Bloomberg View reporter wrote that China “has never really followed through, as overseas firms well know.” He believes that foreign investors are restricted in a lot of ways because “an amazing number of industries remain restricted or off-limits— ‘performing arts groups’ and foreign life-insurance firms, for instance, are still limited to junior-partner status.”

The regulations in China, on the one hand, have opened the doors for foreign investors; but on the other hand, in a lot of foreign investors’ opinions, are catered to protect the growth of Chinese enterprises in certain industries. The German ambassador to China, Michael Clauss, mentioned the increasingly protectionist narrative in China during an interview with CNBC: “The service sector is basically off limits. Many companies that would like to produce here in China and build a factory and start producing are forced into going in a joint venture.” Despite the regulations in the service sector, the most notorious protectionism might be the digital protectionism in China. Simply by blocking other popular foreign sites and apps such as Facebook and Twitter, China has created an authoritarian “internet sovereignty” to allow its own internet companies, such as Tencent and Alibaba, to grow and eventually became internet giants.

China realized that inbound FDI is indispensable in order to achieve economic growth, which led to the new open-door policy. As The South China Morning Post pointed out: “FIEs [foreign invested enterprises] generate more than 20 per cent of sales, employment, and value added in China’s industrial sector…industrial FIEs contribute approximately 10 per cent of China’s GDP just through their own operations.” But because China is getting stronger with the help of foreign investors, it is getting more and more ambitious and is also looking to develop its own strength and capacities in certain industries.

As an old saying goes: “Give a man a fish, and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish, and you feed him for a lifetime.” In order to develop the country’s strength in certain areas, especially those that are already well-developed in western countries, the Chinese leadership has realized that it is important to nourish its own domestic enterprise in a less-competitive environment, to avoid being overpowered immediately by foreign enterprises.

Today, instead of relying on foreign enterprises to make money, China is looking to create more impact on the world market. That is why China’s foreign business policy was carried out in a double track strategy: embracing globalization, while enhancing protectionism.