Shenzhou 13: Blue Planet Outside the Window stands out amid China’s wave of war films as a visually stunning space documentary centered on astronaut Wang Yaping, the first Chinese woman to conduct a spacewalk. While national pride runs through the film, its breathtaking imagery and human focus elevate it beyond propaganda, offering a universal message about shared humanity and life on Earth.

World War Two films have dominated the box office in China in recent months, which is fine for history buffs, but for those members of the movie-going general public who are fatigued with cinematic violence, what is there to watch?

For a breath of fresh air, and something straight out of the blue, how about a film that is literally out of this world, a film made in space?

Shenzhou 13: "Blue Planet Outside the Window” hit Chinese cinema screens last month wedged between films on the Nanjing Massacre, the notorious biochemical Unit 731 and a Korean war flick.

Of all of these, the Shenzhou 13 documentary has the potential to accumulate serious mileage outside of the nationalistic realm, and may even find a niche market abroad.

A showing was arranged in London on September 19, and other overseas airings are likely. It is highly suitable as family fare, and fitting for young space cadets and budding rocket scientists. There’s an ancillary market in museums, classroom screenings and educational TV.

The carefully-scripted narration is thoroughly China-affirming and bound up with nationalism inasmuch as the project represents the fruits of China’s go-it-alone space station drive, but every time the camera turns to the view the Earth floating outside the cabin window, it serves as a powerful reminder that national boundaries are not evident in space and the home planet is a shared one.

In its better moments, the film emulates the better moments of films about the US space program, some of which were burdened with some strongly nationalistic elements.

The inevitable flag-waving, evident on both sides, can be transcended, as in Neil Armstrong’s first words from the moon.

“One small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.”

Half a century later, American language usage has been subject to enough fine-tuning that an astronaut today would be more prone to say, “One small step for a person, one giant leap for humankind” and indeed, this nuance is ably captured in “Shenzhou 13” which features a female astronaut in its leading role.

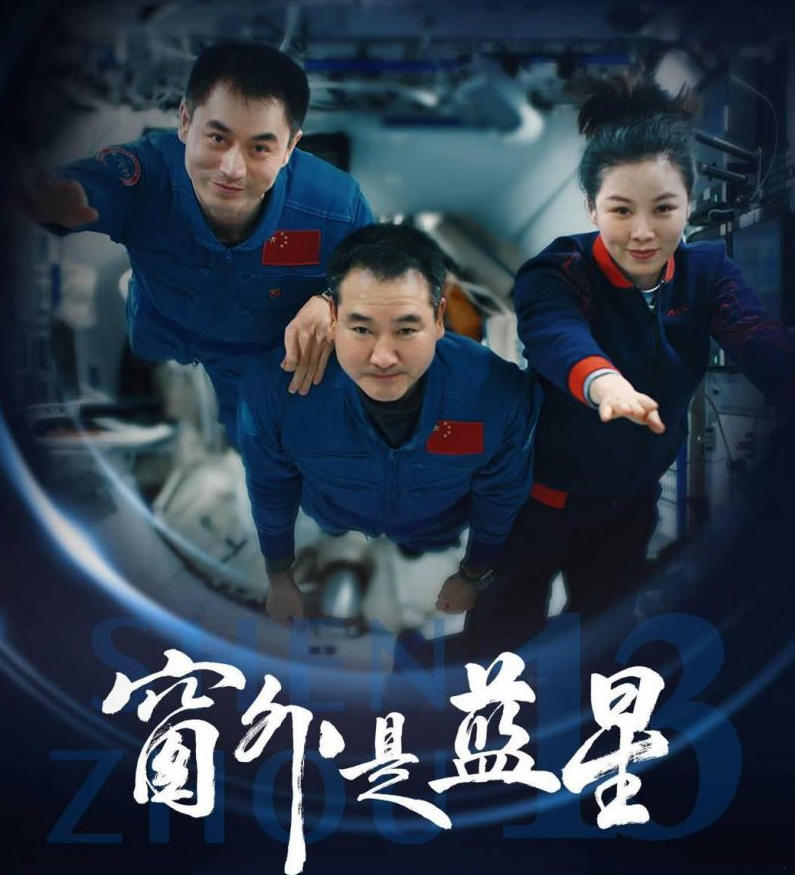

The focus of the film is on a woman in space, the first woman to take a spacewalk, namely Wang Yaping. The audience sees the journey of the crew, from launch to landing, as she sees it. Her fellow astronauts Zhai Zhigang and Ye Guangfu are not without charm and could easily have played Buzz Lightyear-style male prototypes, funny and tough in the their own unique way, but we only get glimpses of them because they are too busy holding the camera and yielding the stage for comrade Yaping’s starring role.

Wang Yaping is good on camera, and keeping the focus on her helps stitch together a compelling narrative in what otherwise would be a garden-variety science documentary.

If any fault is to be found in Wang Yaping’s performance, and it is worth stressing her that she is indeed performing for the camera and never not aware of its looming presence in their cramped quarters, is that her spontaneous comments have a smoothly scripted sound with no surprises, unexpected revelations or insights.

In her defense, she is an astronaut, not an actress, and at times she comes across like a scientist trying to play a star. How else to explain her attention to makeup and the use of red lipstick in outer space?

The scenes of Wang Yaping chatting by video link to her daughter will appeal to the mother demographic in the audience—and anyone who finds it a challenge to balance work and family life. Imagine if your workplace was a space station whipping around the earth at almost 28000 kilometers per hour through a deadly vacuum at an altitude of 400 kilometers. Presumably her two male colleagues miss their families as well, but we don’t get to hear about that.

Wang Yaping’s daughter, like a lot of kids, asks direct questions to which her mother cannot find easy answers. At one point she stresses, “I’ll be right back,” when she has months more to go in space.

I detected one scientific error in Wang’s claim that the Tiangong space station is the brightest artificial star in space as seen by the naked eye from earth. If Elon Musk’s “Ask Grok” AI chatbot is anything to go by, that honor goes to the ISS Space Station:

“Tiangong, being about one-fifth the size of the ISS, is fainter, typically reaching a brightness similar to a bright star, with a magnitude around 0.8 during favorable passes, though it can occasionally approach Venus-like brightness under ideal conditions.” (Grok)

The director, Zhu Yiran, was, for understandable reasons, absent from the set of his own film. But he is credited with training the crew to handle tricky equipment in space:

“We redesigned every part of the camera system to withstand rocket launch vibrations, simplify operation for astronauts, maintain handheld stability in zero gravity, allow fixed shooting from any angle, and enable power charging in the space station…We were granted permission to train the three astronauts over a month.”

The preparations were not trivial, but it wasn’t until the dramatic landing, captured by cameras on the ground and in the air at the landing site, that the director could take the helm with the valuable memory cards in hand and begin the editing of the film in earnest.

Indeed, post-production was rather long, with the film appearing almost four years after the date of the Shenzhou 13 launch. To put the delay in perspective, the crew was in space before the Beijing Olympics and came back after the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The film rightly relies almost entirely on shots made by the crew. This core footage is at times supplemented by matching footage and special effects to dramatize difficult or impossible-to-capture angles for a camera-wielding crew within the spacecraft, such as take-off, landing and the stark loneliness of the space station drifting in space.

The use of supplemental material was judicious, but it should have been labeled as “file footage” or “simulation” as is the practice of CCTV in its news coverage of space flights.

Whether the delay in the film’s release was due to technical difficulties or just China Media Group’s desire to acquire a timely window for theatrical distribution, the September release just before National Day is a good choice. Families looking for something wholesome to take their kids to during the holidays have to look no further than “out the window” at the spectacular space views of the Blue Planet as filmed by the crew of Shenzhou 13.

The quality of the video photography is superb, an excellent application of the relatively untried 8k UHD technology which offers eye-pleasing detail with its 8000-pixel width.

The home planet is a contentious place, and it’s been full of battling nationalisms as long as anyone can remember. Hollywood fare has reflected that from the start, as inadvertent propaganda for the American way, and China’s longstanding film industry, is no stranger to propaganda, either.

But filmmakers at their humanitarian best can do work that transcends boundaries and unites audiences, and it is encouraging to see Chinese directors moving in that direction, producing more world class entertainment.