Amid rising geopolitical tensions, U.S.-China student exchanges, once a cornerstone of mutual benefit, are now under threat from visa restrictions and declining enrollment, risking long-term damage to educational, scientific, and diplomatic ties between the two nations.

On May 28th, Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced that the U.S. State Department would begin working with the Department of Homeland Security to “aggressively revoke visas for Chinese students.” The statement followed a series of restrictions targeting international students at top U.S. institutions.

This development marked another setback for students traveling between the two countries. Once a potent engine of cooperation and mutual benefit, this educational exchange between the U.S. and China has become collateral damage in a broader geopolitical confrontation.

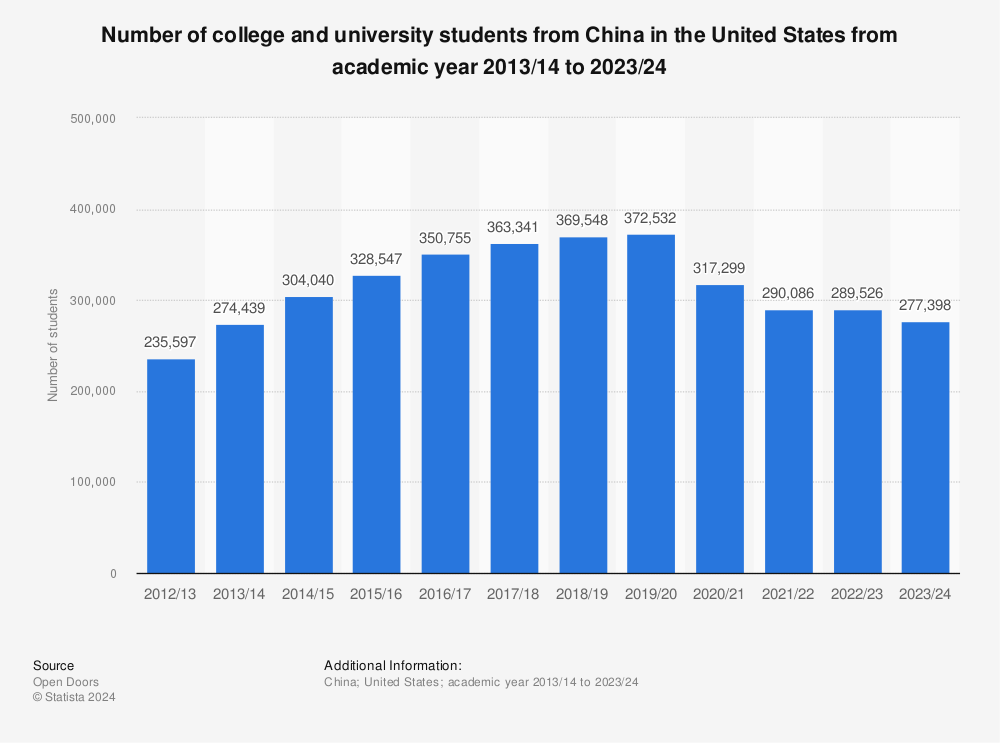

Even before Rubio’s remarks, the cross-Pacific flow of students had been slowing.

The number of American students studying in China, which peaked in 2011 at over 15,000, plummeted to around 200 in 2021 due to COVID-19 restrictions. That number has ticked back up slowly post-pandemic but remains below 1,000.

Chinese student enrollment in the U.S.—long the single largest source of international students—skyrocketed to over 370,000 in 2019, but has declined sharply ever since. In 2023, Indian students surpassed Chinese students as the largest international student group in the United States for the first time since 2008.

These shifts represent more than just enrollment data and lost tuition fees. They mark the erosion of one of the most productive channels of U.S.-China engagement. Students from both nations studying in each other's countries have brought massive and varied benefits to both sides.

Most Chinese students pay full tuition, providing vital revenue for American universities and subsidizing local students tuition and programs. Chinese students’ tuition has especially been a lifeline for many regional universities and communities that struggle to attract the same amount of American students and ensuing revenue.

These students support America’s global leadership in science and technology. Tens of thousands of Chinese graduate students in the U.S. study in STEM fields. They help operate and fund research labs, often performing critical work that powers American innovation. This funding and personnel power will be even more important as federal research funding is cut at the NSF and other federal agencies.

Additionally, many Chinese students remain in the U.S. long after graduation, becoming scientists, engineers, or professors. Numerous valuable additions to the U.S. workforce arrived initially as international students. Macro Polo, an economic research think tank, estimated that in 2022, Chinese students made up nearly 50% of all the top AI researchers but that the majority of them who completed a PhD in the U.S. intended to stay.

When the U.S. forced Chinese nuclear scientists to return home during the Cold War, it didn’t stop their careers—it just meant their research benefited another country. Revoking the visas of Chinese students risks repeating these same mistakes.

When international students study in the U.S., or American students study abroad, they often forge personal links and bonds that could be difficult to sever in moments of tension. This of course applies to Chinese students in the U.S. as well, including the children of political elites. It’s difficult to imagine a full-scale confrontation between two countries when so many lives are intertwined. Many of China’s most reform-minded business leaders and scholars were educated in the U.S., and they’ve played key roles in building bilateral ties.

China also similarly benefits from U.S. students. U.S. students who experience China first hand are more likely to work on China-related issues or build cross-border businesses. They help forge a more comprehensive perspective for a country that has often lacked soft power, particularly compared to the U.S..

These students create a future audience for tourism and Chinese cultural products and bring diversity of thought and new ideas to Chinese campuses. They also help Chinese universities broaden their talent pool and foster connections with the global academic and professional elite, strengthening China’s integration into international knowledge networks.

An equally important, though less visible, benefit is the mutual value it creates: Educational exchange as ballast in the relationship. These students spend time in each other's countries and often develop a more nuanced, sympathetic understanding of American and Chinese society. Their perspectives diversify discourse and lead to more informed policymaking.

Both countries, however, have long had domestic factions that resist these exchanges.

In China, increasingly strict political norms and changes in internet access are difficult for US students to navigate. COVID restrictions were some of the most strict in the world–slowing US students' entry to the country to a trickle and ending several university exchange programs.

In the U.S. during the first Trump administration, there were calls for a blanket ban on Chinese students, citing espionage concerns. While President Trump flirted with these ideas, he ultimately pushed back—reportedly after advice from Ambassador Branstad and others who understood the value of this exchange to the U.S. and its educational system.

The dynamic of Trump pushing back against the hawks in his administration appears to be repeating. Despite Rubio’s harsh rhetoric, Trump said in an underreported exchange at the White House soon after his June 5th call with Xi that, “Chinese students are coming. No problem. An honor to have them.” He further reiterated in a Truth Social post announcing the result of the latest round of trade negotiations in London that he agreed to “Chinese students using our colleges and universities (which has always been good with me!).”

China has shown similar signs of recalibration. Despite previous restrictions on foreign programs and criticism of “Western influence,” Xi Jinping called in 2023 for 50,000 U.S. students to come study in China and increase people to people exchanges. At the beginning of this year, Xi and his wife sent a New Year card to U.S.-China Youth and Student Exchange Association in Washington state, further signaling his personal support for the initiative.

Student exchange is not a side issue. It’s central to whether the U.S. and China can manage competition without catastrophe. Business contracts come and go. Tariffs rise and fall. But relationships built over years—between roommates, lab partners, and professors—lay a deeper foundation.

When Trump and Xi next meet, the headlines will likely focus on tariffs, rare earths, AI, and semiconductor export controls. But one hopes they’ll also discuss education. Restoring and protecting the student pipeline would send a powerful signal: that even amid strategic competition, both countries are willing to invest in mutual understanding.