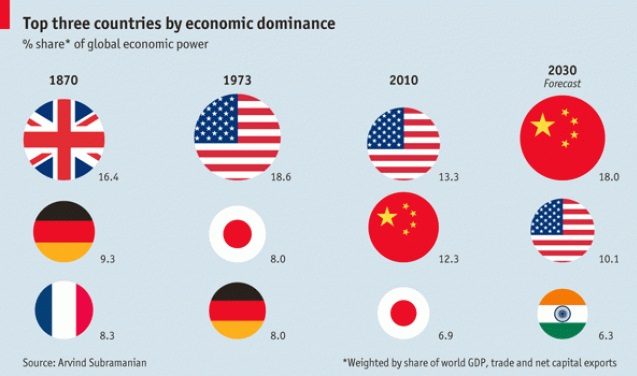

By 2030 China's economy could loom as large as America's in the 1970s. (Economist)

After Joshua Cooper Ramo published his book The Beijing Consensus in 2004, a heated debate about its applicability for developing economies ensued. The Beijing Consensus contrasted the Chinese model of development with the US-centric “Washington Consensus.” Rather than emphasizing the neo-liberal mantra of unfettered market forces paired with deregulation, privatization, and limited government, the China model pursued, according to Ramo, an approach that is flexible and “does not believe in uniform solutions for every situation.”

However, the Beijing Consensus rapidly came to denote an authoritarian form of state-led development. The debate about its applicability generally resulted in the view that this new Consensus was not gaining international traction. Even most Chinese observers concluded that China’s development experiences and national conditions were too unique as to be fully applied abroad.

In the last couple of years the Beijing Consensus has once again become fashionable. The US-centric Washington Consensus, already deeply impaired by the jarring experiences of the 2008 global financial crisis, is being challenged by a new emergent “China model.” This is not an earth-shattering move to a new development doctrine, but rather a gradual shift to a more eclectic view of what works and what doesn’t.

The new China model builds in part on Ramo’s original conception. It emphasizes unconventional approaches to economic policy, including a combination of mixed ownership, basic property rights, and heavy government intervention. But most importantly, it consists of a new conception of how to face developmental challenges, contrasting substantially with the Washington Consensus.

To be clear, proponents of the Washington Consensus always failed to appreciate the diverse nature of developing economies. Countries facing developmental challenges invariably pick and choose certain aspects of a policy package, combining it with unique national factors and the developmental experiences of other, often more successful neighboring economies. Unsurprisingly, economies that closely followed the one-size-fits-all package of the Washington Consensus have not fared too well. Mexico for example, attempted to follow many of its policy prescriptions, but is still underperforming.

The China model actually builds on several aspects of the Washington Consensus, but is far less dogmatic. Fiscal and monetary prudence, an emphasis on private initiative and entrepreneurship, and the government’s role in establishing good soft and hard infrastructure for economies to thrive are basic commonalities. Despite these similarities, its basic characteristics are novel and provide developing economies with new ideas on how to develop.

The first aspect of the model is perhaps the most central. It emphasizes establishing a relatively clean government that can effectively implement policy. Comparatively speaking, the Chinese government has always been rather effective in policy implementation. With the anti-corruption campaign initiated by Xi Jinping in late 2012, the country has also witnessed what is likely to be the largest purge of corrupt practices and officials in history. This does not imply that the campaign is without problems, but it has had the approval of most Chinese citizens, and it has reduced the most egregious corrupt practices in the Chinese system.

The second characteristic of the model concerns efforts to establish integrated physical infrastructure and, more generally, great developmental pushes. China itself has started to lead several such efforts abroad, especially via the Asian Infrastructure Development Bank (AIIB) and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). For many developing economies these initiatives de-emphasize market-opening reforms that can have unintended consequences, like undermining national productive capacities. Rather, they favor physical infrastructure projects that can directly benefit national economies while enabling them to better participate in the global economy.

The third aspect continues to stress the central focus of Ramo’s Beijing Consensus: pragmatic and eclectic economic policy approaches that incorporate a variety of methods. One of the lesser known successes of the Chinese reform experience has been its experimental approach. Distinct sites for economic experimentation are set up, such as special economic, industrial, and trade zones. These enable lots of tinkering and bottom-up initiatives to tease out reform solutions while controlling for unintended consequences.

This experimental approach is directly feeding into the fourth aspect of China’s new development model. As Xi Jinping made clear during his speech at the 19th Communist Party Congress in October 2017, China aims to be at the forefront of technological innovation and environmental consciousness. Already the country is making great strides in the development of cutting-edge technologies, ranging from high-speed rail to electric vehicles and quantum communications. Much of this is occurring against the backdrop of unbridled private entrepreneurship that nonetheless benefits from government support. This combination of private initiative with massive state-guided investment stands in stark contrast to the Washington Consensus. While it has to be adapted to local conditions, it has broad applicability across a range of development challenges.

The final aspect is also the newest. Chinese leaders have hitherto shied away from outlining a vision of development with global applicability. Ideological propositions during earlier reform era Party Congresses focused on China’s own development challenges. This is changing.

At the 19th Party Congress, Xi Jinping outlined his thought on socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era. Rather than emphasizing the development of GDP, corporations, or markets, the central focus rests on putting people at the centre of development, while creating harmony between humans and nature. Most significantly, this vision reaches beyond the Chinese people to promote “the building of a community with a shared future for mankind.”

Following the 19th Party Congress, the Chinese Communist Party hosted in early December 2017 a dialogue with world political parties. The document issued following this meeting was dubbed the “Beijing Initiative.” It directly builds on the 19th Congress’ new guiding theory and holds that its innovative theoretical and practical outcomes do not only hold significance for China, but also provide good examples for the development of other countries, especially developing countries.

Putting forward a global vision is rather new for Chinese leaders. China’s economic transformation now allows it to advance international initiatives, such as the BRI. As a result, China sees itself as taking on a global leadership role while formulating a new vision based on China’s own development experiences.

Historically speaking, it is still too early to judge the global reception of these efforts. Nonetheless, certain aspects of the emergent China model are already being adopted by developing economies. Saudi Arabia, for example, has emerged as a rather unlikely candidate, but one whose recent initiatives clearly resemble the Chinese mold. “Vision 2030” aims to reduce the kingdom’s dependence on oil, while diversifying its economy and making it a leader in other industrial fields. Its remit is broad, encompassing not only economic initiatives, but also many social and cultural reforms. In fact, many of its development pushes resemble Chinese initiatives and fit with Beijing's BRI infrastructure plan. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman has also launched a sweeping anti-corruption campaign that resembles Xi’s efforts to root out corruption in China.

“Vision 2030” received considerable criticism due to its overly ambitious goals. It is also not a wholesale adaptation of the Chinese experience, since the two countries face very different conditions. But it shows that the China model is gaining international traction. Since the model has no coherent set of development principles like the Washington Consensus, its formulations remain conceptual and fluid. Perhaps this is an inherent strength: its open-ended nature enables multiple interpretations of pathways to development. In fact, as the Washington Consensus fades, we are unlikely to witness a wholesale shift to a Chinese development dogma. Rather, the emergence of more varied views on what works and doesn’t in economic development could be the China model’s greatest contribution.