Nepal’s EV surge, powered by Chinese technology and domestic hydropower, has displaced India’s industrial influence and exposed weaknesses in Delhi’s regional strategy. While it marks a shift in regional power, the transformation remains fragile, reliant on subsidies and foreign supply chains.

Electric Vehicles in Nepal. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Nepal’s electrification goes beyond a green success story and marks a geopolitical breach. By aligning Chinese technology with domestic hydropower, Kathmandu has displaced India’s industrial presence to the margins and redrawn South Asia’s power grid on its own terms. What presents as climate policy is a direct refusal of dependency.

China’s Quiet Infiltration of India’s Backyard

More electric vehicles (EVs) are now sold per capita in Nepal than in the United States. Over two-thirds of new passenger car sales are electric, with Chinese models claiming 80 percent of the market—displacing decades of Indian automotive dominance. In under five years, Chinese manufacturers have redefined the economic vectors of a country once tethered to Indian supply chains.

Furthermore, with no domestic car industry, no capital reserves, and some of the world’s harshest terrain, Nepal has emerged as one of the most electrified car markets. The shift has outgrown its environmental frame, turning into a tool of economic statecraft with consequences that reach deep into the regional balance of power.

This pivot did not emerge from ideology—it was built on coercion. The 2015 Indian fuel blockade, masked as constitutional concern, exposed Nepal’s dependence. Their leaders faced a brutal reality check. Dependence on Indian oil through Indian-controlled supply chains meant vulnerability to their political whims. The response was precise: eliminate import barriers for EVs and punish fossil-fuel cars with duties exceeding 250 percent.

Yet customs reforms were only the entry point. Nepal’s central bank turned EV lending into a national priority—offering up to 90 percent financing—terms that were revolutionary in South Asia. Simultaneously, its dormant hydropower sector began generating stable electricity for the first time in decades. That convergence of liquidity and infrastructure became the base of a new economic order.

Chinese manufacturers seized this opening with characteristic speed and precision. BYD, MG, and others flooded the market with vehicles priced to undercut Indian rivals. Within five years, they replaced not only Indian brands but also India’s energy dependence. Each electric kilometre driven now reflects a triple victory for Beijing: industrial exports, market dominance, and expanded influence in a space traditionally shaped by Delhi.

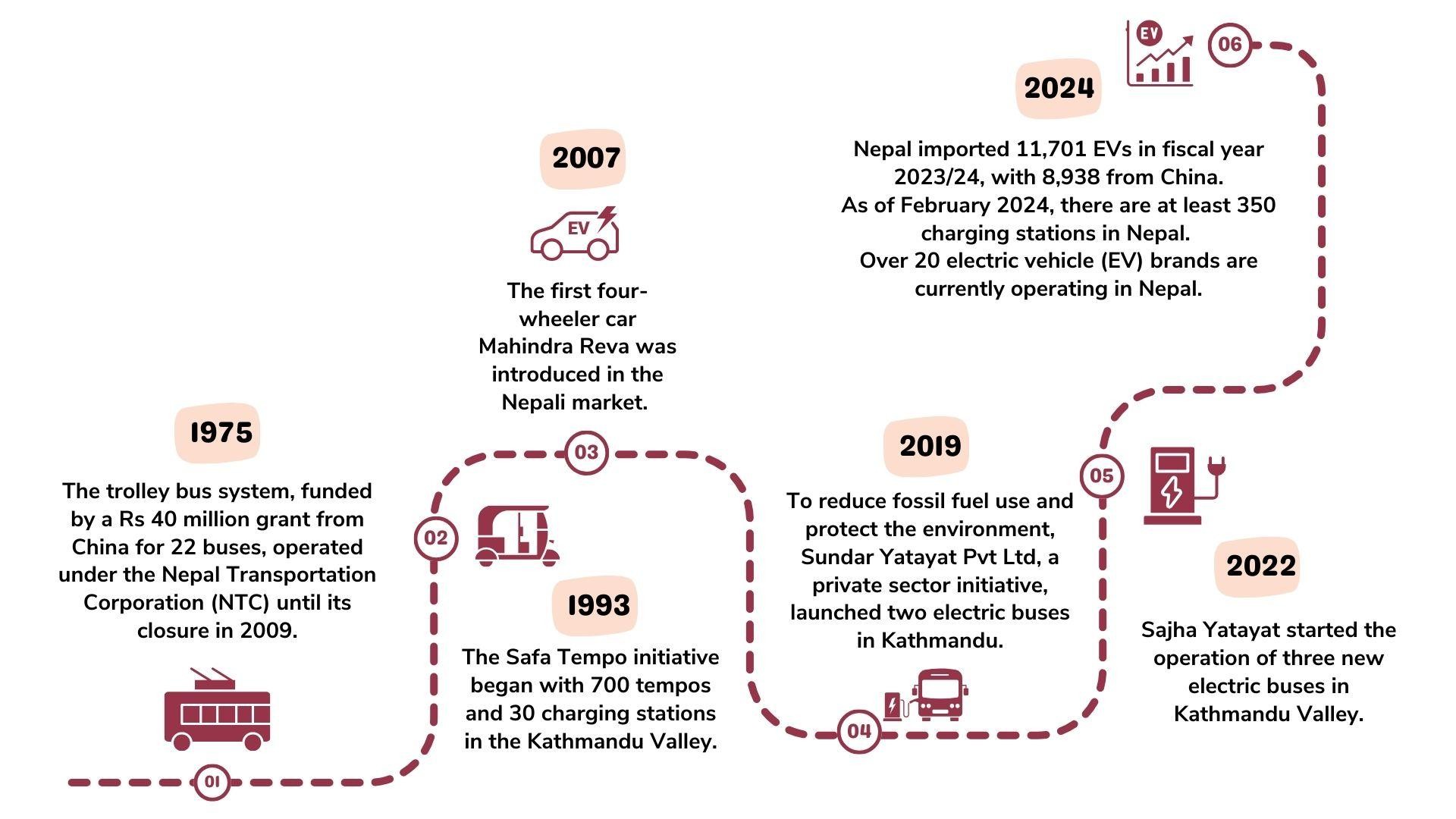

Timeline of the Evolution of EVs in Nepal (Graphic copyright: Nepal Economic Forum)

The Displacement of Dependency

Hence, this penetration represents a remarkable strategic accomplishment. Nepal—landlocked, mountainous, with 30 million people and no natural role in the Indo-Pacific theatre that drives China’s String of Pearls strategy—became Beijing’s most successful beachhead in Delhi’s immediate neighbourhood. Where maritime chokepoints and harbours-naval bases define Chinese expansion elsewhere, in Nepal the success came through consumer finance and charging infrastructure, creating a pathway to influence that bypassed traditional geopolitical constraints entirely.

The achievement exposes profound limitations in India’s regional strategy. Delhi has spent decades positioning itself as a democratic alternative to Chinese authoritarianism, courting Western support for its role as a geopolitical counterweight. Yet when technological competition arrived at its doorstep, India lacked the tools to respond. The country that promotes itself as a rising power could not produce industrial capacity competitive with Chinese imports in its own backyard. This failure undermines not just Indian influence in Nepal, but the broader Western assumption that India can serve as an effective check on Chinese expansion.

Indeed, India’s ambition to lead the Global South rests on a fractured regional foundation. The 1950 Treaty of Peace and Friendship gave Delhi economic and social intimacy with Kathmandu—open borders, cross-border livelihoods, and a rhetoric of shared kinship. For decades, this proximity translated into dominance: India built roads and controlled fuel supplies.

But proximity bred self-satisfaction. Resentment over the treaty’s asymmetry and recurring border friction festered beneath the surface. When China entered through the Belt and Road Initiative in 2017, it did not confront India directly—it displaced it. EVs became the quiet tool. Where Delhi relied on inherited ties and fossil fuel pipelines, Beijing offered batteries, supply chains, and financing. China did not demand loyalty; it delivered products.

The shift unfolded without proclamation. As India projected influence through rhetoric, China reconfigured Nepal’s mobility in practice. Roads once built by Delhi’s aid now lead to Shenzhen’s showrooms. Fuel trucks gave way to charging stations. What had been a symbolic geography of dependence is now a material geopolitics of replacement.

China’s approach was effective. It converted infrastructure diplomacy into everyday utility, embedding Chinese brands into Nepal’s streets rather than just its policies. It sidestepped the political weight India carried, presenting alternatives free of historical baggage. And it turned commercial access into enduring influence, not through declarations, but through constant, visible presence.

The geopolitical implications extend, therefore, beyond bilateral trade flows. Nepal’s EV boom signals how clean technology transfers are becoming instruments of soft power competition. China’s battery supply chains, manufacturing scale, and export financing now shape consumer choice in ways that traditional political influence cannot match. When Nepali families choose Chinese EVs over Indian petrol ones, they’re not just making environmental choices—they’re participating in a broader realignment of regional economic gravity.

Yet beneath this success lies structural fragility—an opening China could exploit to deepen its presence, or one India could leverage for re-entry. Nepal’s public charging network runs on unsustainable subsidies. State-backed stations sell electricity at 6-11 Nepalese Rupees per kilowatt-hour—US$ 0.04-0.08—, cheaper than what rural households pay to light a room. The pricing wins praise but distorts the market. Private operators, forced to pay commercial tariffs of 15-25 Rupees, cannot compete. The result is a two-tier system where public subsidy undercuts private investment, stalling long-term infrastructure growth.

Nepal has seen this before. The micro-hydro boom of past decades followed a similar curve—explosive growth fuelled by concessional financing, followed by stagnation when subsidies disappeared and maintenance costs mounted. Over 3,000 plants now sit idle or underused. Without cost-reflective pricing and capital discipline, the EV sector may follow.

The distortions extend to class structure. In a country where car ownership is rare and public transport systems need rebuilding, subsidizing private EV adoption could deepen rather than bridge inequality gaps. The policy prioritizes visible consumption over systemic mobility solutions, creating perverse incentives where buyers—typically urban and affluent—receive indirect transfers from general taxation that could fund mass transit serving broader populations.

Power Rewired, But Not Yet Secured

For India, the lesson is stark. Influence based on nostalgia collapses when competitors deliver real competitive advantage. Delhi’s Neighbourhood First policy has become a slogan unmatched by infrastructure or industrial offerings. In contrast, China’s clean tech strategy pairs manufacturing depth with export engineering, generating influence faster than treaties or grants.

That swap—fuel for current, India for China—represents a realignment. Dependence remains, but its form has shifted. Nepal’s gamble reveals the new structure of power: battery supply, hydropower stability, and logistics integration. Oil pipelines and fuel diplomacy no longer shape the periphery. The country that once waited on Indian tankers now runs on Chinese batteries powered by local dams.

The question is whether Nepal can turn this momentum into durable sovereignty or remain a proxy market under a new configuration of foreign control. That outcome depends on a reset. Subsidies must give way to commercially viable infrastructure. Regulation should attract capital, not displace it. Public investment must serve as a catalyst, not a fixture. Energy policy should promote national integration over fragmented consumption. Above all, Nepal must stop mistaking foreign presence for national progress.

Sustaining this advantage means institutionalising the transition beyond subsidy-driven infrastructure. The real benchmark is not the volume of EV imports, but the creation of a self-reliant ecosystem—one resilient without Beijing’s factories or Kathmandu’s subsidies. Until then, electrification remains a simulation of sovereignty: domestically fuelled, but externally steered.