Hong Kong remains a vital and distinct gateway between China and the world, with its common law system and international character serving essential functions for China's global engagement and soft power. Despite rising geopolitical tensions and U.S. policy shifts, particularly under Trump, Hong Kong can preserve its relevance by investing in education exchanges, hosting unofficial Sino-American dialogues, and positioning itself as a hub for global governance debates.

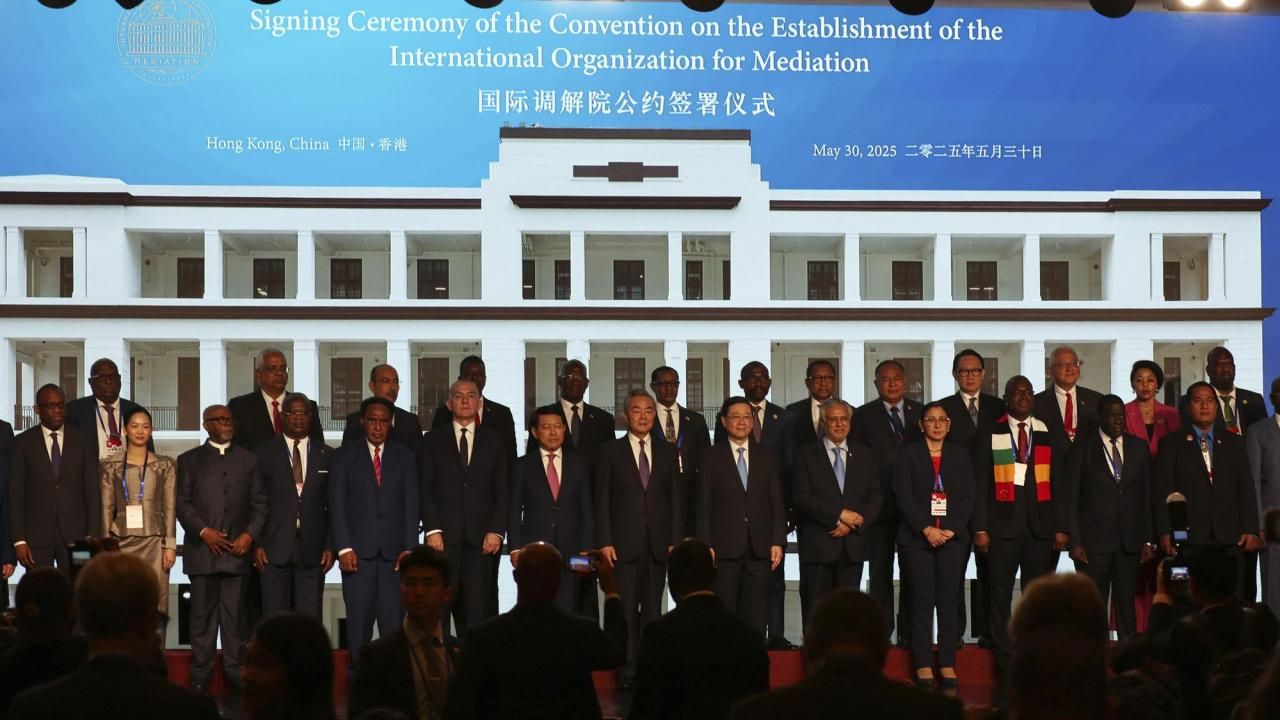

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, center, attends the signing ceremony of “the Convention on the Establishment of the International Organization for Mediation”, in Hong Kong, May 30, 2025. Representatives of more than 30 other countries, from Pakistan and Indonesia to Belarus and Cuba, signed the Convention to become founding members of the global organization.(Photo: Jonathan Lee/AP)

Since the mid-19th century, Hong Kong has served as a conduit, a node, and a fluid exchange for ideas, capital, and talents – from China into the rest of the world, and the international community into China. The city has persevered – and indeed, thrived – through the ebbs and flows of geopolitical flux. From the Cold War to the two major financial crises of 1997 and 2008, it has re-emerged stronger – time and time again, even whilst the odds are stacked against us.

Indeed, it strains credulity to think that in one of the most populous, state-driven, and socialist economies in the world, stands a low-tax, tariff-free, capitalist, and fundamentally internationalist city. Yet the distinctiveness of Hong Kong serves a fundamental purpose – not just for its 7.5 million denizens, but the 1.4 billion people comprising the Chinese population.

To nationalistic naysayers and critics within China who contest that the city has benefited from far too many “exceptions” and “discretionary treatments”, the words of Chinese President Xi Jinping on July 1st, 2022, reflect the practical case – the raison d'être – for Hong Kong’s enjoying a different legal, economic, and political system from mainland China: to advance “China’s sovereignty, security, and development interests”.

Pledging that “One Country, Two Systems” is to be continued indefinitely, Xi twice highlighted the “common law” of Hong Kong as a sui generis stand-out feature about the city – its ability to continually demonstrate and advocate before the world its judicial independence and autonomy, is integral in assuaging foreign firms and businesses of their worries about doing business in China. It is for reasons of pragmatic experimentation that China needs Hong Kong to remain different – in order to facilitate its capital transactions, economic engagements, and cultivation of its fledgling soft power, in relation to the rest of the world.

Without its internationally recognisable rule of law, much of Hong Kong would come to nought – and the senior leadership in Beijing sees few self-serving reasons in advancing the blurring of legal boundaries between the two. If anything, Hong Kong’s judiciary can and should serve as an example for reforms in the mainland.

What is Trump 2.0’s “Hong Kong Policy”?

Yet there are clear headwinds that stand in the city’s trajectory. Domestically, the bureaucratic logic renders it the case that select administrators, bureaucrats, and politicians in the city would tend to “look over their shoulders” and partake in “second-guessing” – in seeking to enact more zealously than required, if at all intended, what they construe as orders from the very top. As is customary of the Chinese political system at large, actions that are viewed as “politically safe” tend to be amplified and exaggerated along the complex chain of command, whilst actions that may be economically, symbolically, diplomatically conducive but not maximally “safe”, would thus be deprioritised.

Internationally, the American political establishment has become increasingly drawn to treating Hong Kong as but a part of its overarching China policy. During his first term, U.S. President Donald Trump ended the city’s special trade status with the U.S. – as first agreed upon in 1984. In targeting individual officials with sanctions over their purported response to the 2019-20 protests, his administration weaponised the economic interdependence between the city and the U.S., in accelerating the continued political estrangement and breakdown in trust. Beijing viewed these measures as aggressive acts of provocation; conservatives within the establishment saw these changes as necessitating the appointment of officials with fewer ties – professional, educational, or otherwise – with the U.S., who would be immune from the long-arm jurisdiction of the State Department.

Whilst former President Joe Biden by-and-large kept Hong Kong open as a window of backchannel and tacit engagements, upon Trump’s return to the White House, the push to discursively de-legitimise Hong Kong’s “One Country, Two Systems” arrangements has once again taken central stage in shape Washington’s Hong Kong policy. Trump’s team has rolled out tariffs of up to 145% for goods imported from mainland China and Hong Kong – opting to overlook the fact that the two are independent jurisdictions per stipulations of the World Trade Organization.

Gone are the days when the U.S. President would openly praise the “open system that is essential to Hong Kong’s stability and prosperity” – the range of important institutional differences that existed, and yet still remain between the mainland and Hong Kong. The overarching rhetorical consensus has shifted into the convenient and cursorial invoking of particular individuals of political sensitivity and hasty, sweeping assessments of changes in civil and political liberties to make the fatalistic point, “Hong Kong is over!”

The International Organisation for Mediation’s headquarters at the site of the old Wan Chai Police Station. (Photo: Dickson Lee)

The Path Forward for Hong Kong

In truth, Hong Kong has been wounded by the past decade of geopolitical turmoil – but is by no means over.

In a piece co-authored six years ago for TIME Magazine, I argued that Hong Kong’s relations with the rest of China are in urgent need of reform – constructive changes that would take seriously the voices of ordinary Hong Kongers, embrace fully the diversity and heterogeneity unique to the city, as well as enabling the city to add value to China’s relationship with important counterparts, including the U.S..

There are three key priorities that the city must pursue, in order to retain relevance in an age of increasing fragmentation in the global order, but also specifically in relation to the bilateral relationship between China and the U.S.

Firstly, education is crucial as a bridge-building tool. The Hong Kong private sector must play a leading role in facilitating the creation of more scholarships, research grants, and infrastructural support for scholars and students alike coming from the U.S. Ethnic Chinese scientists and researchers who find themselves increasingly targeted under the neo-McCarthy-ist atmosphere in the U.S., would stand to gain from Hong Kong’s open arms. Indeed, top universities in the city have seen a significant influx of prominent scholars in the political and social sciences.

Expanding the scope of recruitment to encompass bright, “third-cultural” fresh graduates – who may hail from the Global South, have spent extensive periods of their education experiences in the United States, and are looking for a conveniently positioned base relative to their countries of origin, could well emerge to be instrumental bridges between the proverbial “East” and “West”. Yet the dismantling of preconceptions and stereotypes must begin at a younger age – secondary schools (especially international schools) should set up partnerships with counterparts in the U.S., in exploring the prospects for exchanges.

Keeping these engagements relatively low-profile – to avoid undue politicisation and the resultant scrutiny – will require a significant degree of tact. As such, the less official governmental involvement, the better. The goodwill and interest on the part of family offices, philanthropists, and non-profit organisations that find it difficult to operate in the legally opaque and insular mainland, can and should be tapped into to set up such collaborations.

Secondly, Hong Kong must position itself as a bridgehead for unofficial Sino-American track-II engagements. The city can strive to play host to a larger number of sub-national (e.g. state-level, city-level, or even local-level) dialogues and interactions between the mainland and the United States. In 2023, Californian governor Gavin Newsom commenced his trip to China with a visit to Hong Kong – which saw him interact with a significant number of domestic stakeholders from different backgrounds and orientations. Sub-national collaboration over culture, the arts, and the environment can and must continue over the coming years.

Non-government actors with access to key political players, whether they be former officials, established investors, or respected academics, can also play a pivotal role in relaying credible signals and messages – even amidst, and indeed given, the discombobulating spectacles coming from career politicians. The University of Hong Kong recently hosted former U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Kurt Campbell – whose visit exemplifies fully the autonomy and strategic value of Hong Kong-based higher education institutions, as comparably more open and liberal spaces for unfettered discussion over the bilateral relationship.

Finally, in the era where our world is increasingly riddled with the onset of challenges pertaining to automation of labour, public health crises, food and energy shortages, it is imperative that Hong Kong steps up to become a bastion for vital debates and deliberations over global governance. From managing the fall-out of AI-enabled automation on labour markets, to navigating discrepancies in compliance standards in developmental or green financing, there are many areas where Hong Kong should strive to fill the niches.

The beauty of this proposal lies with its ability to play to the city’s strengths. Rather than seeking to outstrip and outcompete its neighbours in the Greater Bay Area on fronts of advanced manufacturing, Hong Kong should become the primary nexus where the politics and policymaking surrounding these issues can be hashed out in full. It is oft said that China and the U.S. should cooperate over issues such as climate change, AI safety, and public health challenges – but with what purpose in mind, and in accordance with what sorts of rules and norms? These are the questions into which more resources must and should be dedicated in China’s most open city.

None of this will be easy. None of this can occur without extensive striving on the part of the private sector and the civil society. Yet between cynical realism and pollyannish idealism, there is always a third way.

As the late scholar Joseph Nye once said to me, “China and the U.S. need more folks who believe in their mutual greatness – and that whilst they are fundamentally different countries, there is also much that their people share in common.”

May his spirit live on.