Source: Provided by Verian for the European Parliament (last update 14/06/2024)

The 2024 European Parliament (EP) elections require a deeper analysis beyond surface-level results. Exploring the nuances and dynamics offers insights into how national issues and broader geopolitical factors will shape Europe and beyond.

This year’s elections followed the historical trend of using them as a platform for expressing discontent with incumbent national governments, or for governments to deflect blame onto Europe for their own mistakes. National issues took center stage in debates across member states.

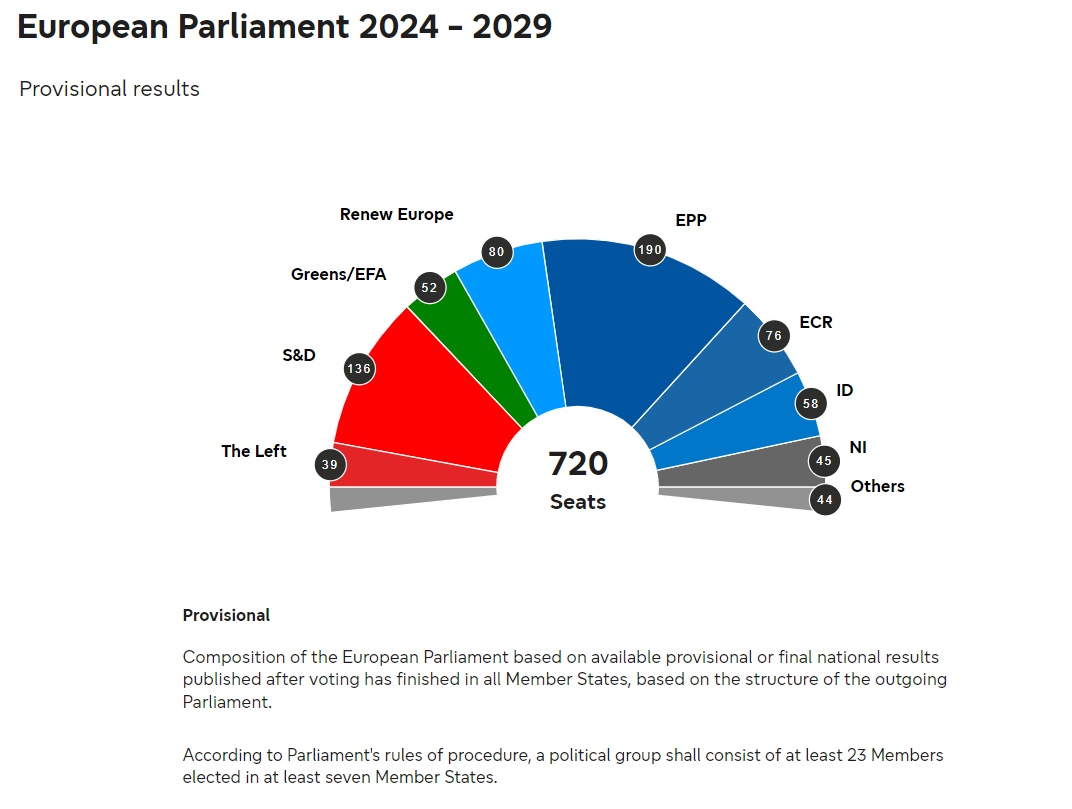

The growing center-right presence (European People’s Party-EPP), the left-wing losses (Socialists & Democrats-S&D, Greens), and the consolidation of far-right parties—potentially becoming the second force in the EP—reflect local political scenarios. While established parties provide stability, the rising influence of extremists could test EU unity.

Indeed, the decline of the centrist Renew, traditionally supporting mainstream parties (EPP & S&D), signals uncertainty in major decisions. This particularly pertains to immigration policies and the “green deal,” already under heightened scrutiny from citizens, businesses, agriculture, and the political factions that spearheaded these initiatives, hinting at inevitable repercussions.

Parliament President Roberta Metsola during election night at the European Parliament in Brussels.

Perhaps most concerning are the defeats of governing parties in France and Germany sending shockwaves that threaten the foundations of the agreements of the past 70 years.

Le Pen’s far-right Rassemblement National victory prompted Macron to call a snap election. Though it won’t alter the French Presidency until 2027, major adjustments may follow, potentially leading to cohabitation. Will such a government influence the EU towards protectionism, criticize Islam, and affect the environmental agenda or the support for Ukraine?

In Germany—with 96 EP seats out of 720—, the government’s downfall propelled the extreme-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) to second place after the Christian Democrats’ resounding victory. How Chancellor Scholz’s zeitenwende responds to this humiliation—the poorest historical outcome ever—remains to be seen.

Spain vividly epitomizes these developments. The People’s Party won, while Renew vanished. The polarized campaign remained entrenched in a corruption scandal involving the prime minister’s wife—an issue under European prosecutor investigation but irrelevant to future EU policies. Meanwhile, the Socialists capitalized on fears of an extremist surge, echoing outdated anti-fascist rhetoric. Notably, far-right parties support or govern in seven EU countries and Spanish regions and municipalities without causing significant disruptions beyond the customary anti-immigration discourse, typically mirrored by the far-left.

Like other European leaders, Sánchez governs with the support of far-left parties, leaving citizens questioning why these alliances are deemed healthier by the mainstream media to those maintained by their ideological rivals. For example, Italy’s Prime Minister Meloni, elected in October 2022 on a hardline rhetoric and populist platform, has since garnered near-unanimous approval from European leaders for her pragmatic governance. Her electoral victory validates her effectiveness, while the number of immigrants arriving in Italy has not decreased. Furthermore, Rome has been building its own profile within the EU, particularly with the momentous work of former PMs Draghi and Letta.

Hungary serves as a stark reminder of the disparities between nationalistic rhetoric and European institutional realities. Despite government propaganda, illiberal Budapest continues to receive substantial EU funding, fueling liberal infrastructure projects that would otherwise remain mere fantasies. Will Orbán pull Hungary out of the EU? Despite Fidesz’s national-populist campaign motto of “Occupy Brussels! No migration, no gender, no war!” the tangible financial benefits it reaps suggest a different reality.

These examples underscore a shift in Euroskepticism and anti-Europeanism—from challenging the European project as a whole to nitpicking its finer points, often cynically exploited for domestic political advantage. Delving deeper, the vulnerabilities of France and Germany’s leaders, the innovative role played by Italian outstanding figures, and the persistent discontent of smaller states with von der Leyen have collectively cultivated fertile ground for potential changes in EU leadership.

Indeed, the perceived impact of these elections is often overstated. Although the Parliament decides on the Commission President nomination, requiring 361 out of 720 votes, the selection process is predetermined by state leaders, who retain their positions unchanged from before the election (excluding the resigned Belgian PM). The Parliament lacks autonomy in choosing individual Commissioners, a power resting with state leaders. For instance, in Spain, despite the People’s Party emerging victorious, the Socialist Prime Minister will select the commissioner without consulting them.

In addition, while the Parliament shares legislative power with the Council, it cannot initiate legislation—a prerogative of the Commission. Members of the EP, though crucial in fostering European identity and representing the citizens, often adhere to national party lines, resulting in significant noise but limited real impact, especially regarding non-binding resolutions that attract global attention but lack tangible effects within Europe. In short, the trajectory of EU politics isn’t determined within the EP.

Undeniably, the most influential political events for Europe in 2024 and 2025 will unfold beyond the continent, notably the U.S. elections and the trajectory of China-EU relations. Closer to home, the Russia-Ukraine war remains the most critical security concern. Distinguishing between political events and paradigm shifts is crucial in geopolitics; EP elections fall into the former category, while American elections represent the latter. However, understanding who will run the EU is essential for predicting what will come next.

Currently, both the Parliament and the EU as a whole have insufficient geopolitical clout to address these global challenges effectively. Trump’s potential return—coupled with heightened hostility towards the EU— significant trade dependencies on China amidst its market closeness and retaliatory measures against EU de-risking and economic security strategies, and a latent escalation of Russian assertiveness—exemplified by recent events in Georgia—highlight the intricacies to navigate.

Additionally, the allocation of “top jobs” in Brussels may yield unexpected outcomes. Power struggles among the current EU leaders—von der Leyen, Michel, and Borrell—have had noteworthy implications for governance. Their discord, particularly regarding the EU’s China policy, has led to a lack of internal coordination, conflicting messages, weakened policy direction, and diminished global influence. As the Commission holds greater sway than the Parliament in this regard, the upcoming nominations will be pivotal in defining U.S. and China’s roles in Europe’s future.

Thus, the EU must restructure decision-making processes across its institutions to achieve results faster in a swiftly evolving geopolitical setting. Introducing specialized task coordination units could expedite vital projects and reforms, overcoming policy gridlock and propelling transformative changes essential for Europe’s progress. Achieving strategic autonomy and evolving into a genuine geopolitical actor depend on forming a common defense independent of NATO and reinforcing industrial competitiveness, as emphasized by Draghi and Letta. This includes creating a permanent financial instrument.

These urgencies underscore notable oversights by von der Leyen, especially in her approach to the EU’s China policy, perceived as overly influenced by Washington. Additionally, her personalized stance on immigration deals with Tunisia and Egypt, investigations into alleged wrongdoing in vaccine negotiations, as well as her support for Israel during military operations in Gaza targeting civilians, have sidelined key economies like France, Germany, Italy, and Spain. These lapses have created the ground to seek a candidate who can better represent the diversity of states and institutions within the EU.

Political maneuvering and backroom deals—reminiscent of von der Leyen’s own election—could play a role in this realignment. The EP election and the new distribution of power could serve as a pretext for such arrangements, influencing the future direction of EU leadership until 2029.

All in all, if Europe truly aspires to ascend as the “third superpower,” the time for decisive action is now.