At the 25th China-EU Summit in Beijing, Chinese and European leaders acknowledged both overlapping interests and deep divergences, especially over China’s seeming alignment with Russia and the Ukraine war. While Beijing seeks improved economic ties with Europe, it continues to prioritize geopolitical security and its strategic rivalry with the U.S. over European concerns, limiting the prospects for major diplomatic improvements.

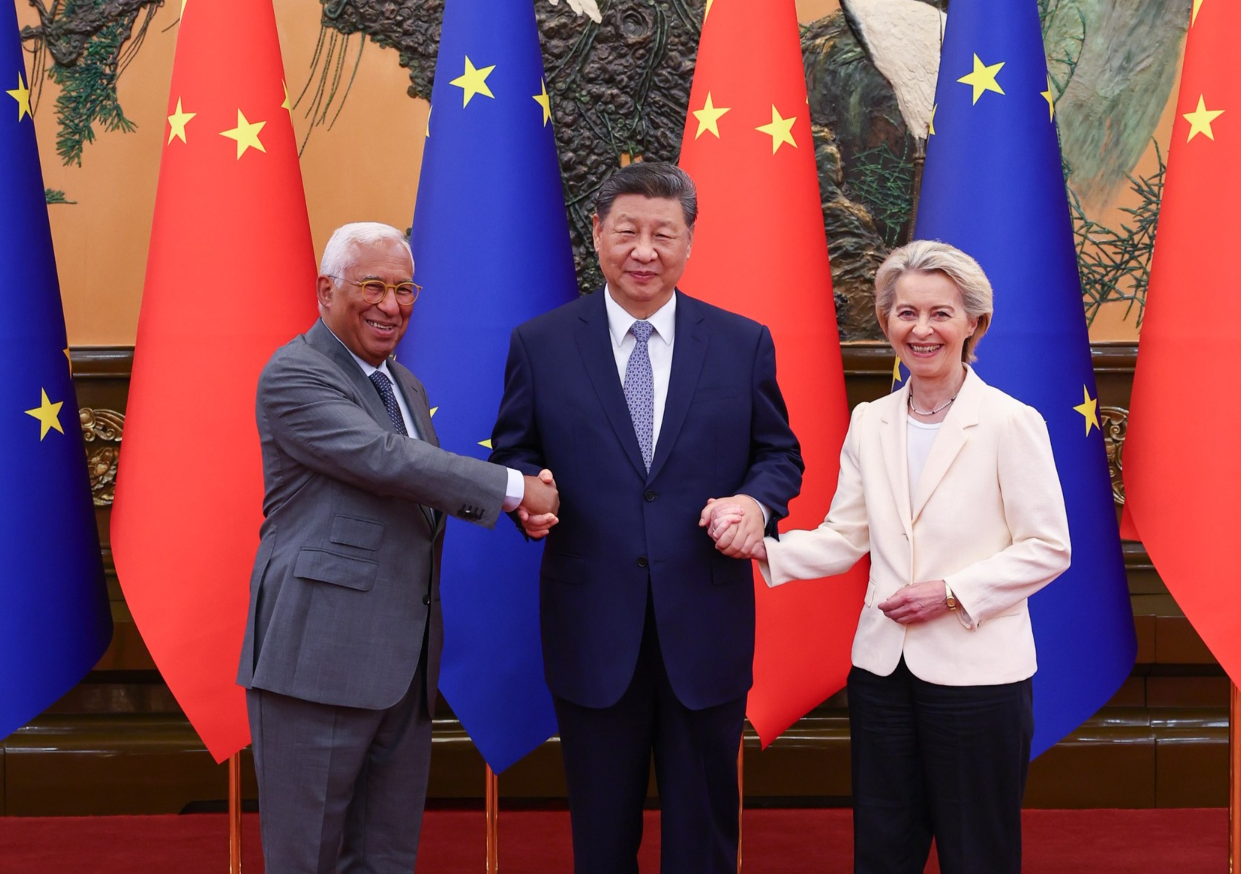

Chinese President Xi Jinping met with EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen (right) and Council President António Costa (left) in Beijing at the 25th China-EU Summit, July 24th, 2025.

On July 24th, Chinese President Xi Jinping met with EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and Council President António Costa in Beijing at the 25th China-EU Summit, which was to commemorate 50 years of formal diplomatic relations. The summit was abruptly reduced from two days to one, as a request from Beijing.

Von der Leyen expressed to Xi that the Sino-European relationship is at an “inflection point”, and emphasised the need for “essential” rebalancing in trade – and beyond. To understand how Sino-European relations have gotten to where they are today, we must examine more closely the key dimensions along which their interests converge – and where divergences are more conspicuous.

Where Chinese and European Interests Converge, and Where They Come Apart

There are certainly areas in which the interests of China and most European nations converge. Both parties are experiencing significant strain under the surging protectionism and capricious trade postures from Washington. Diplomats in Beijing and Brussels have undergone arduous negotiations with their American counterparts, who are adamant that they “ameliorate” the purportedly “unfair” trade deficits between the U.S. and these two economies through purchasing more American goods – wholly and conveniently overlooking, of course, the sizeable utility American consumers have gained from high-quality, cheaply produced imports. If China and the EU were to succeed in lowering their mutual trade barriers for capital and firms from the other, this could well go some way in offsetting the pressure induced by the “shrinking” American pie – within their respective growth portfolios. Indeed, the recently secured EU-US trade agreement – with ostensibly manageable levels of tariffs – has only amplified the woes of European producers impacted by heighted trade barriers with the US.

Yet where their interest convergence ends, lies with geopolitics. Beijing views Moscow as a crucial strategic partner – albeit not an ally – in its push for a world order that is no longer unilaterally dictated by the proverbial West. For many states in the EU – especially those who have had to live and suffer under the atrocities of the USSR – preserving Ukrainian sovereignty and territorial integrity is a non-negotiable (even if, in practice, infeasible) demand. Indeed, the trenchant determination with which European nations have doubled down on backing Ukraine, has both impressed and surprised the powers that be in the Chinese foreign policy establishment. In February 2022, many in Beijing had expected European governments to cave into Russia’s imperious demands – just as their predecessors had in the past.

Additionally, in the era of supply chain reshoring and friendshoring, security-minded bureaucrats in both China and the EU have gained growing momentum. Alarmed by China’s invoking of export controls over its rare earth supply in its dealings with the U.S., wary voices in Europe are pressing for accelerated de-risking from China across strategically important industries. On the other hand, conservative security and ideological officials in Beijing have balked at any perceived attempt by foreign powers (including the EU) to interfere with their domestic affairs – i.e. in criticising China’s model of governance and approach to the Taiwan question, which Beijing sees as a purely internal affair.

Finally, the current Chinese leadership has placed much emphasis on China achieving a highly competitive – if not dominant – lead in cutting-edge technologies and advanced manufacturing, particularly in renewable vehicles, lithium batteries, and solar panels (the “New Three”). The resultant successes of the emergent industry champions have alienated a significant number of domestic producers in the EU, who perceive themselves as victims of Chinese counterparts who have ostensibly received “unfair subsidies” (though the substantiation and evidence remain in part questionable). The more robust China’s lead in these sectors, the greater the antagonism and backlash towards Chinese goods, from vested corporate interests in the EU.

What does Beijing actually want from Europe?

Given this complex entanglement of interests and incentives, where does Beijing stand on Europe? How are we to interpret the recent flurry of diplomatic activity, in conjunction with China’s apathetic stance on the Ukraine question?

Existing signs point to a complex picture. On one hand, the struggling Chinese economy would certainly benefit from a more receptive European market – especially in light of the tightening grip from the U.S. In his most recent visit to Europe, CPC Politburo Member and Foreign Minister Wang Yi called upon Brussels to join Beijing in opposing “unilateralism and bullying” – framing Washington as a threat to their shared economic interests. A month or so prior, China announced it would lift sanctions on members of the European parliament – imposed during a vicious dispute over China’s human rights record a few years ago. These gestures reflect that Beijing’s foreign policy establishment is increasingly cognisant of the potential – and keen to signal its acknowledgment of the standing – of Europe as an independent pole in a multi-polar world order. Lest this be ambiguous, an editorial put out by state-affiliated Global Times in February this year explicitly made this pitch.

Moreover, recent announcements by the Chinese State Council concerning price-based competition amongst EV makers seemingly reflect an appreciation of the perils of over-capacity – not only in the context of the domestic economy, where the leadership has noted the inefficiency and excess in the skewing of resources towards a few saturated sectors, but also in relation to opprobrium from foreign audiences. From the very top has come the signal that neijuan competition (involution) in the Chinese economy must be reined in – though questions remain over the exact measures to be implemented, and their efficacy.

Some may posit that Chinese leaders are still missing the elephant in the room – that is, none of these concessions would matter, independently of a serious reorientation of Beijing away from Moscow. That is, these measures do not tackle at all the deeper objections raised by European leaders – that the Sino-Russian partnership is inimical to European security interests.

Yet this reading suffers from what can only be termed strategic naivete.

Consider an alternative possibility: what if Chinese leaders were well aware of the outsized importance of the “Ukraine issue” to the bilateral relationship – yet remain fundamentally reticent to act upon such knowledge? In other words, the crux lies less with “misunderstanding” or “miscommunication”, and instead with raw, realist geopolitical calculus.

Firstly, Chinese commentators have long taken issue with what they perceive to be explicit double standards from the West in relation to India’s and China’s stance on the war in Ukraine. Global Times op-eds penned in 2022 – 2024 repeatedly noted that India had considerably deepened its trade ties (especially over oil) with Russia since its invasion of Ukraine, but received little to no criticism from the West. More recently, state media have adopted a more positive frame – highlighting the legitimacy of trade between countries such as Brazil, China, India, and Russia, which all comprise BRICS member-states.

Secondly, Beijing may care about its relationship with Europe, yet its strategically fixated establishment views as more weighty a concern its standing in the great power rivalry with the U.S. From a realpolitik perspective, the more the U.S. and NATO allies are bogged down in Ukraine, the less energy and ammunition they have to encircle and isolate China in the Indo-Pacific – this is the rationale embraced by the current diplomatic establishment. Indeed, one can also throw into the mix the prospects of a State Department and National Security Council under Marco Rubio that are seeking to pull off a “Reverse Nixon”, which has alarmed many in China wary of a rekindling of ties between the US and Russia.

The weltanschauung of the incumbent leadership clearly ranks security above economics, and China’s weathering the onslaught of American coercion above the potential benefits China stands to gain from a more receptive Europe. Whilst such rankings are not inflexible, it would take some fairly sizeable upsides for Beijing’s priorities to be reversed. Accordingly, Beijing’s strategic posture is only understandable – even if disagreeable for many in Brussels.

Thirdly, Beijing has become increasingly jaded about the strategic unity – and hence strength – of the European bloc. Senior foreign policymakers are unconvinced that the payoff from courting Europe, via putting strategic distance between China and Russia’s militaristic aggression, would be worth the costs. For European countries with deeply ingrained scepticism towards China, mere movements and shifts on the war alone will not cut it in nudging their populations to look the other way. For countries with long-standing ties with and increasing dependence upon China, there is no need to duplicate efforts – if trade and investment can settle the question. These reasons explain the apparent tardiness with which Beijing has pursued substantive rekindling of its ties with Europe.

Where Lies the Glimmer of Hope?

From Europe’s perspective, the only glimmer of hope rests with shoring up its credibility, in terms of the sticks or carrots it can bring to the table. Whilst much emphasis has been placed upon the former, it is clear that Brussels has thus far eschewed severely punitive measures towards Beijing, on grounds that they would be deeply unconducive towards the bloc’s economic vitality on the whole. Businesses wary of Chinese export capacities are equally wary of being shut out of Chinese manufacturing grounds.

The only meaningful alternative, perhaps strangely, lies with carrots. If Beijing can be convinced that the possible upside from its taking a more emphatically neutral and contextually Europe-aligned stance on the war in Ukraine, which would in turn behove the European bloc to offer a non-NATO-centric solution to the crisis at hand, there yet remains some room for change and hope. In the absence of the EU getting its act together as such, the scales in Beijing would remain tipped in favour of security over economics, and coy apathy, over a genuine commitment to brokering enduring peace that is fully embracing of Ukrainian security interests. This is the political reality with which Europe and China alike must contend.