U.S. restrictions on visas and growing uncertainty for international students and skilled workers, contrasted with China’s rollout of more permissive talent visas, are reshaping global education and career decisions and making the United States a less attractive destination for emerging and established talent. As competition for innovation increasingly mirrors economic decoupling, sustained limits on mobility and collaboration risk undermining cross-border knowledge exchange, even as long-term scientific and technological progress continues to depend on international talent flows and institutional cooperation.

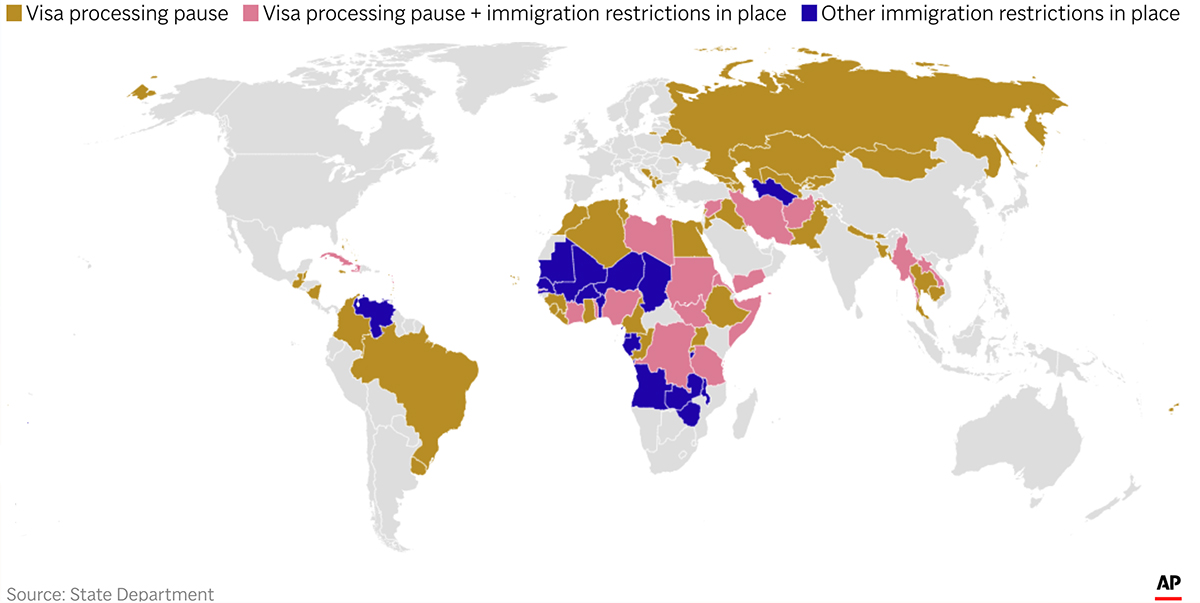

The Trump administration has indefinitely suspended immigrant visa processing for people from 75 countries. The freeze takes effect on 21 January, 2026.

Washington’s recent announcement of a visa pause on 75 countries, including allies such as Thailand and Brazil, is making headlines globally. Universities and exchange programs scrambled for details, concerned that student visas — not just work visas — were implicated in the statement.

Less reported on was China’s announcement of its K visa mid-way through 2025, aimed at attracting young foreign talent in science and technology. The visa streamlines the application process and allows people to reside in the country before having a job offer from a company, making it much easier for fresh graduates to move to China to start their career or a business. The details remain vague and there’s been concern from young Chinese that foreign competition will make it harder for them to find jobs, but the release was unmistakably well-timed with the U.S. announcement of a 100,000 USD fee for H1B visa holders. Last week’s announcement ratchets up even more anxiety for highly-skilled H1B workers in the U.S. who are struggling to understand the repercussions for their families and careers, many of whom are firmly established professionals in leadership positions.

For those at the beginning of their career, the U.S. now looks less inviting. As career and study locations are inevitably correlated, the announcement will impact decisions on where to pursue education. Until recently, international students were drawn to the U.S. in hopes of gaining employment after completing their degree. Now, the number of international students pursuing a U.S. degree, while still the highest globally, will likely decrease significantly. This includes Chinese Mainland students, who make up nearly a quarter of the international student population at top U.S. universities.

Where will Chinese mainland students go instead? A large number are choosing Hong Kong. Hong Kong positions itself as the super connector between China and the rest of the world, an international city where Chinese businesses can explore global opportunities and international businesses can explore Chinese markets. For Chinese mainland students, it is a place where they can dip their toes in international settings by speaking English in the classroom and interacting with international students and faculty. It offers a nearby, global yet comfortable education experience, one that now seems less risky than the previously more popular U.S. universities or even the second most popular, Australian institutions.

For the University of Hong Kong, the increase in Chinese mainland students was so significant that it had to double some entry-level courses while dealing with strained housing capacity just before the 2025 school year started. Based on recent rankings, these students aren’t sacrificing quality either. HKU ranked 11th globally in the newest QS World University Rankings, moving up 6 spots from last year. Five of the city’s universities consistently rank in the top 100 globally.

America still hosts the most globally ranked universities, highest funding for R&D, and ability to attract competitive faculty given it spends the largest percent of tertiary education funding by GDP. But recent news has also focused on some high-profile talent exits. Chinese media features stories of highly qualified Chinese-American professors returning ‘home’ — most recently, chemical engineer Zheng Yu, who moved from MIT to Peking University. Last year, Nobel laureates Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee left the U.S. for the University of Zurich. The fact that the U.S. has over 3 times more Nobel laureates than the second ranked country, Germany, doesn’t alleviate the concern of a talent exit from the U.S. For American university recruiters, the recent news makes it more difficult to convince international students and their parents that the U.S. still wants them.

Competition for international talent feels increasingly intense, framed as a one-time, zero-sum game where limited global talent will pick a location and play out a career. Countries seem to be shoring up talent within their borders to ensure they have the intellect needed to fuel their own innovation. The rhetoric mirrors economic narratives of decoupling: shoring up limited resources within borders and striving for self-sufficient supply chains. Economists in both countries question the feasibility of decoupling the U.S. and Chinese economies, but are we seeing an even more impossible attempt to decouple talent?

At first glance, decoupling and competing for talent may seem like a logical national pursuit. Talent can be measured in research dollars, patents or innovation IPOs. Those are all registered by country. Teams that write papers, win grants, start companies, and patent innovations have a physical address in a country. And countries like to promote those numbers to prove they are winning the innovation game (China dominates the global patent race with record filings). But how many of those teams are single-nationality with ideas sourced solely within their borders?

Innovators commonly practice cross-border idea pollination. Limiting research to problems, answers, and minds within borders is impossible in some fields, and greatly restrictive in most others. Researchers and academics don’t need convincing, but they do need assurances they won’t be penalized for their international collaborations.

Even if our relationship is one defined by competition, the U.S. and China can benefit from talent and innovation exchange. As we build up competition spaces and new multilateral institutions, we can also build innovation coupling spaces. We can strengthen the associations, science labs, and professional exchanges that bring American and China talent together to share knowledge. For years, organizations like the China-United States Exchange Foundation in Hong Kong and the East-West Center in Hawaii have fostered environments where top Chinese and American minds can bring forth fresh ideas on AI, media, philosophy, environment, and more. Such institutions provide mechanisms and venues for talent regardless of passports.

Students obtaining credentials, professionals building their careers, and innovators working on breakthroughs are making choices based on opportunities presented (or not) by their own and other countries. By encouraging international collaboration and safeguarding spaces of joint innovation in the right fields today, we can prevent a damaging decoupling of talent tomorrow.