China’s decision to forgo special rights in the WTO shows that it takes its great power responsibility seriously. It wants to advance trade cooperation with developed economies and with Global South. A trade upturn with the United States in 2026 is much anticipated.

During a high-level meeting on the Global Development Initiative (GDI) at the United Nations headquarters in New York on Sept. 23, Chinese Premier Li Qiang announced that China won’t seek new special, differential treatment in WTO negotiations.(Photo: Wang Zhuangfei / CHINA DAILY))

Chinese Premier Li Qiang announced at a meeting related to the United Nations General Assembly on Sept. 23 that, China, a major developing country, will not seek new special and differential treatment in World Trade Organization negotiations, either now or in the future.

Logically, it would melt America’s complaints that China has benefited disproportionately from its developing nation status in the WTO. It gained a considerable “unfair” competitive advantage over the U.S. and Europe, the story goes. Washington has long complained that China maintains a huge trade surplus worldwide, particularly with the United States. Former U.S. president Bill Clinton has even expressed regret over decision to accept China’s into the WTO. Marco Rubio, the U.S. Secretary of State, claimed recently that as a result of China’s WTO accession and its S&DT status, it has changed capitalism while capitalism has failed to change China.

China-U.S. trade

S&DT was first demanded by large numbers of developing economies at the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in 1964. Because of their relatively less-developed economies and industry, they were unable to compete with developed economies at the same tariff level and with the same market access in the same transition period — or in the same condition of most-favored nations.

In 1968, UNCTAD agreed to award general, non-mutual benefits and non-discriminative favorable mechanism, or Generalized System of Preferences (GSP), for developed economies, providing much lower tariffs on products from developing economies. In 1979, the GATT parties conference authorized a legal basis for GSP, which became part of GATT 1994. The World Trade Organization replaced GATT in 1995 but inherited all the GATT rules that defined special and differential treatment. According to UNCTAD in October 2000, S&DT included 155 measures.

S&DT has played a big role in promoting the economies of developing economies, especially low-income economies, or LDCs. Over the past 30 years since the WTO was founded (1995), the share of world export by middle- and low-income countries increased from 17 percent to 34 percent, and the population in poverty fell from 40 percent to 10 percent of total population.

China qualified for S&DT from the first day of its WTO membership as a developing economy and did benefit from GSP. However, unlike what the critiques in the West have complained about — that China had benefited tremendously from WTO S&DT — China actually used very limited S&DT. Some statistics show that it only benefited from 15 S&DT measures out of total of 155. On the contrary, China took voluntary market access measures. According to the final agreement from the Uruguay round, the WTO’s developed members committed to a lower average tariff rate of under 5 percent, and developing members committed to under 10 percent.

As of this year, China’s average tariff level was 7.3 percent, and the trade weighted average was 4.4 percent — very close to the level of developed members. China has cut its negative list drastically, removed all restrictions on manufacturing market access and opened most of its service sector to foreign investors, far ahead of most WTO developing members.

During the WTO talks on the COVID-19 vaccine intellectual property waiver, China also gave up the transition period (the right of a developing member). Starting in December last year, China awarded zero tariffs to 53 LDCs in Africa, a special treatment usually awarded by developed economies.

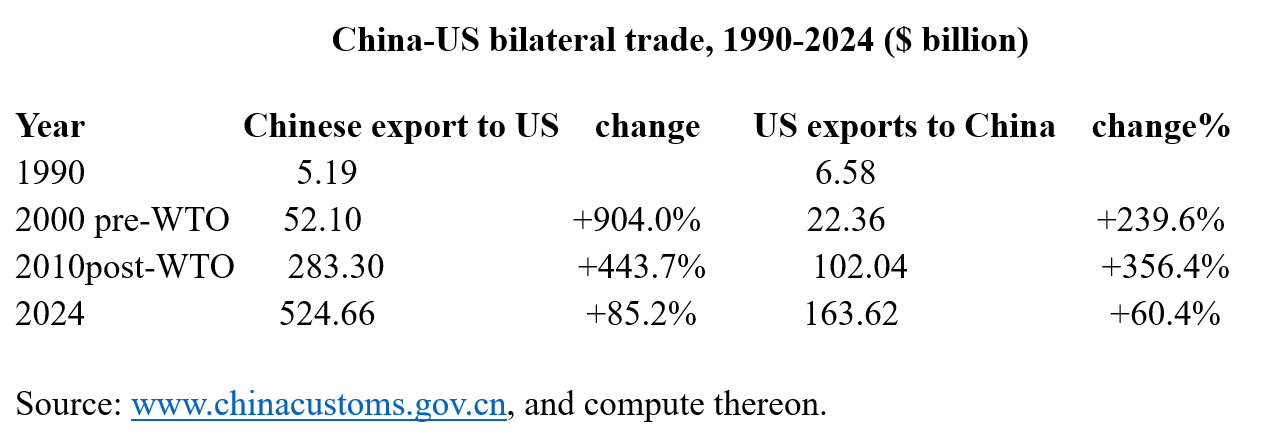

The trajectory of China-U.S. trade also shows that, because of limited S&DT, Chinese exports to the United States did not shoot up after WTO accession. The fastest growth actually happened before China’s accession to WTO, during the 1990s. China’s exports to the U.S. shot up from $5.19 billion in 1990 to $52.11 billion in 2000, up 904 percent, while U.S. exports to China grew from $6.58 billion to $ 22.36 billion, up 239.6 percent. We can see a heavily lopsided rate of growth in favor of China. During the subsequent 10 years 2001-10 — after China’s WTO accession, —China’s aggregate export growth to the U.S. slowed to 443.7 percent, or half the speed of the previous decade. Meanwhile, U.S. export growth to China accelerated to 356.4 percent. During the second decade after China’s WTO accession, both Chinese and U.S. exports slowed sharply, but at a similar tempo.

China’s WTO accession actually accelerated U.S. exports. During the 2001-23 period, U.S. global exports grew by 183.1 percent, while its exports to China grew by 648.4 percent, or 3.5 times faster. It has been proved that China has used limited S&DT and consequently has not gained much advantage in trade with the United States.

New push for trade

China’s official rejection of S&DT should be enough to calm U.S. complaints. There will be no special treatment for China, nor is there any point in Washington hedging on China’s developing economy status, as China will not resort to it. Rather, it will follow the high standard of MFN and market access, the same as developed members. In future WTO negotiations, China will take similar offers by developed members. It is especially significant in future negotiations on cross border e-commerce and possibly on digital trade.

This will be especially constructive for future China-U.S. bilateral trade arrangements. China and the United States should talk about a possible basket of tariff arrangements based on very low tariffs, according to WTO developed member standards. If workable, a new arrangement should replace the current U.S. tariff on China and China’s counter-tariff on the United States. In that scenario, both sides could see stable, mutually beneficial trade growth in coming years.

China and the U.S. could also talk about new, high-standard market access for two-way investment. With no S&DT, China will lift the opening-up of its market to a higher level —without any new special treatment in market access or business environment — providing a friendlier market for all foreign investors, including American multinationals. China and the U.S. could advance talks about high-standard digital security collaboration and market access.

The WTO will have its 14th Ministerial Conference (MC 14) in Cameroon in March 2026. The key issue on the agenda is WTO reform. China’s latest decision will provide new momentum for this agenda, and new cooperation between China and the United States will be much anticipated.

This does not mean, in any sense, that China is no longer a developing economy — quite the contrary. Its per capita GDP in 2024 was only $13,303, lower than the World Bank threshold for a high-income economy which is currently $13,935 and lower than the global average per capita GDP of $13,673 in 2024. It was half that of Slovakia, which was $26,148, the bottom rung of developed economies.

However, there is no need for the United States to hedge on the question of China being a developing or developed economy, because China voluntarily will not enjoy any new S&DT. Its decision shows that it takes its great power responsibility seriously. It wants to advance the global multilateral trading system and reform the WTO. And it wants to advance trade cooperation with developed economies and with Global South. Undoubtedly, China-U.S. trade will get a new push and new facilitation. A trade upturn in 2026 is much anticipated.