The first Trump–Xi summit since 2025 brought high hopes and headline deals on trade, fentanyl, and rare earths, but diverging goals and ambiguous promises hint at the fragility of this latest U.S.–China rapprochement. The United States secured pledges on curbing fentanyl flows, increased agricultural purchases, and the removal of export controls on rare earths, while emphasizing symbolic gains in respect and stability.

Chinese President Xi Jinping meets with U.S. President Donald Trump in Busan, South Korea, Oct. 30, 2025. (Xinhua, Shen Hong)

President Xi Jinping and President Donald Trump convened on the sidelines of the APEC conference in Busan, South Korea in October. Their meeting lasted a brief 100 minutes but has been framed as both productive and cordial. As the first encounter between the two leaders since Trump began his second term in January 2025, the engagement carried considerable diplomatic weight. It also took place against a backdrop of renewed economic tension, following the United States’ recent imposition of port fees on Chinese vessels and China’s introduction of expansive new export controls on rare earth elements.

From the outside, it appears that both sides had legible, distinct objectives they outlined for one another, with the United States focused on securing practical economic gains and demonstrating that the administration, and Trump himself, can manage one of America’s most complex bilateral relationships.

What did the U.S. want?

Removal of Export Controls on Rare Earth Minerals

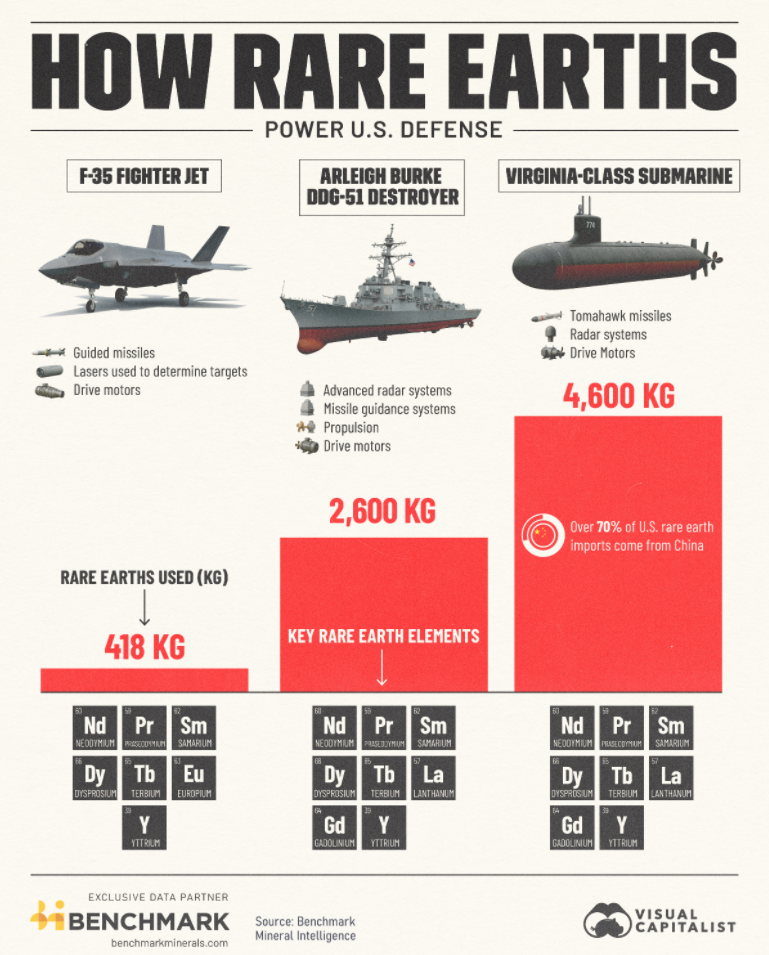

The rare earth issue emerged as perhaps the most urgent and unexpected concern for the United States going into the Busan meeting. China’s sudden announcement of export controls on rare earth elements had come as a shock to the U.S. policy community, which viewed the move as a sharp escalation at a time when bilateral relations had shown tentative signs of improvement. Stockpiles of these materials had already been depleted by restrictions earlier in the year, leaving the United States acutely vulnerable. As Ryan Grimm, group vice president of the Purchasing Supplier Development of Toyota Motor noted, “[The restrictions] can shut us down in two months—the entire auto industry.”

For Washington, the timing and scope of China’s export restrictions represented not only an economic challenge but also a political one. For many policymakers on both sides of the aisle, the rare earth dispute assumed an existential significance (perhaps even greater than China intended), underscoring the urgency with which Trump’s negotiating team approached the issue.

Curbing the Flow of Fentanyl and Fentanyl Precursors

Curbing the flow of fentanyl into the United States has been one of the signature themes of President Trump’s second-term agenda, standing alongside immigration enforcement and tariff policy as a central pillar of his domestic and foreign strategy. The administration’s framing of the March 2025 tariff increases as the “fentanyl tariff” illustrated the extent to which the issue has come to the forefront of Trump’s policy. For Trump, it serves as both a policy focus and a rhetorical bridge, linking the themes of law enforcement, border control, and the defence of “American families” that have defined his political brand since 2016.

From a policy standpoint, the issue also offers a rare “low hanging fruit.” Even during the lowest points of the bilateral relationship under the Biden administration, China had shown a degree of willingness to regulate the production and export of chemical precursors used in synthetic opioids. Chinese authorities had introduced new licensing systems and criminal penalties targeting illicit exporters, measures that U.S. officials acknowledged as meaningful though incomplete.

Increased Agricultural Purchases

Agricultural trade has long served as both an economic and symbolic barometer of U.S.–China relations, and it occupied a prominent place in President Trump’s objectives at Busan. Indeed, in the hours following the meeting, Trump highlighted the issue as his foremost achievement, writing on Truth Social: “I was extremely honored by the fact that President Xi authorized China to begin the purchase of massive amounts of soybeans, sorghum, and other farm products. Our Farmers will be very happy! In fact, as I said once before during my first Administration, Farmers should immediately go out and buy more land and larger tractors. I would like to thank President Xi for this!”

Trump’s decision to lead with this announcement reflected both political calculation and long-standing priorities. Since the early stages of the U.S.–China trade conflict, American farmers have borne much of the economic cost of tariff escalation. Increased Chinese purchases thus carry substantial domestic resonance, offering a direct and visible benefit to a constituency central to Trump’s political base. Beyond electoral considerations, the administration viewed agricultural exports as a key metric of “fair trade” and as tangible evidence that Trump’s coercive negotiation style could yield results beneficial to U.S. producers.

The Intangibles: Respect, Peace, and Stability

For Trump, personal rapport with foreign leaders is not merely a matter of tone but a measure of success itself—proof that his instinct-driven, personality-based approach can yield stability where traditional institutional processes often falter. In a series of Truth Social posts following the meeting, Trump wrote that “This meeting will lead to everlasting peace and success. God bless both China and the USA!” and declared that “America is respected again—RESPECTED LIKE NEVER BEFORE!” He went on to emphasize that “There is enormous respect between our two countries, and that will only be enhanced with what just took place. We agreed on many things, with others, even of high importance, being very close to resolved.”

Under this current administration, such imagery is both diplomatic theatre and political strategy. Emphasizing “respect” and “peace” reinforces his self-portrayal as a dealmaker capable of restoring American prestige without resorting to conflict. By presenting the Busan meeting as a triumph of respect and mutual understanding, Trump seeks to reframe the U.S.–China relationship as evidence of his ability to command deference abroad and deliver calm at home.

What did China want?

Tariff Relief

A central priority for Beijing in Busan was achieving relief from the constantly expanding and extensive network of U.S. tariffs that had begun during Trump’s first term and increased significantly in the early months of his second. These new measures, justified in Washington as part of a broader strategy to “rebalance” trade, had compounded the difficulties already facing Chinese exporters amid a period of domestic economic structural shifts. Securing even a partial reduction was therefore a key diplomatic and economic objective.

The announcement that the United States would lower tariffs on Chinese goods from 57 to 47 percent represented a limited but symbolically significant concession. For Beijing, the move suggests that negotiation remains an effective channel for addressing U.S. pressure and that the Trump administration is open to transactional compromise. Domestically, the outcome allowed Beijing to frame the meeting as evidence that China’s more assertive approach could yield tangible results.

Removal of Port Fees

Another major concern for Beijing was the newly imposed U.S. port fees on Chinese vessels, announced this past summer. Although modest in direct economic scale, the measure carried strong political overtones. From China’s perspective, the fees were an unnecessary provocation, and an assertion of maritime leverage that implicitly questioned China’s right to be a global trading power. For Beijing, resolving the port fee issue would demonstrate that China could retaliate economically, using its own economic pressures to roll back what it regarded as coercive U.S. behaviour.

A Good Relationship with Trump

Beijing also entered the Busan meeting intent on cultivating a personal relationship with President Trump. For China, the Xi-Trump relationship presents risks but also opportunities: when managed effectively, it allows for flexibility and direct influence that are often absent in dealings with more conventional U.S. administrations. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ (MOFA) readout of the meeting reflected this emphasis on tone and symbolism. It says that President Xi stated that “China and the United States should be partners and friends. This is what history has taught us and what reality needs.” Xi’s remarks positioned the relationship as one of mutual responsibility between two captains steering through turbulence.

Proof that Beijing’s Strategy is Working

The Busan meeting marked the clearest evidence yet that Beijing’s evolving diplomatic posture is producing results. Over the past five years, Chinese foreign policy has undergone a significant transformation—from the assertive, sometimes abrasive “wolf warrior” style of the late 2010s and early 2020s, to a more withdrawn and reactive stance during the later Biden administration, and now to a renewed phase of proactive but disciplined engagement.

During the Biden years, Beijing largely concluded that meaningful progress in the bilateral relationship was unattainable. Frustrated by sanctions, export controls, and diplomatic isolation, Chinese officials adopted a strategy of restraint: limiting communication and focusing on diplomacy with third countries.

By contrast, the Xi–Trump meeting in Busan signalled a new phase of confidence. Beijing’s recent use of economic tools, such as export controls on rare earths and the suspension of U.S. soybean purchases, demonstrated a willingness to take initiative and set the terms of engagement. Crucially, this is not a return to “wolf warrior” diplomacy. Instead, it represents a more mature and calibrated form of diplomatic assertiveness: China applies pressure where it holds leverage, while maintaining a tone of partnership and collaboration. The success at Busan, measured both in tone and in substance, will reinforce Beijing’s confidence that proactive, transactional diplomacy can yield concrete results.

Outcomes of the Meeting

In the immediate aftermath of the Busan meeting, both governments projected a sense of accomplishment. The tone of official statements, readouts, and social media posts suggested that each side believed it had secured meaningful gains.

President Trump framed the outcomes as proof of his ability to negotiate favourable terms, citing China’s supposed commitments on fentanyl, rare earths, and agricultural purchases. Beijing, for its part, emphasized the renewal of “dialogue and cooperation,” presenting the meeting as evidence that China’s more proactive strategy is producing tangible results.

Yet beneath the celebratory language, the substance of the agreements remains uncertain. The White House fact sheet released after the meeting outlined several Chinese pledges but provided few details on implementation or timelines. Chinese ministries have thus far confirmed only portions of these commitments, leaving questions about scope and enforcement unresolved. Beijing’s public messaging has emphasized “consensus” and “mutual understanding” rather than binding agreement, suggesting a preference for flexibility over formal obligation.

Nonetheless, both sides appear convinced that they achieved the upper hand, a dynamic that carries both promise and risk. On one hand, mutual satisfaction could encourage a period of relative stability and continued engagement; on the other, it may foster overconfidence, with each side believing it successfully managed the other. History shows that such moments of perceived equilibrium in U.S.–China relations often precede new tensions, as unspoken expectations collide with policy realities. The Busan meeting, therefore, may be remembered less for its specific outcomes than for the fragile optimism it temporarily restored.

What will the Relationship Look Like in 2026?

Looking ahead, 2026 will likely be defined by both high-level symbolism and the slow unravelling of differences beneath it. Up to four meetings between the two leaders are planned for next year (Trump to Beijing in April and Shenzhen for APEC in November; Xi to the U.S. for G20 and an official state visit in the second half of the year).

Washington and Beijing have each released their own versions of what was agreed, and while the two accounts are similar in spirit, the specifics of realisation diverge. As implementation proceeds, it is likely that Trump will become frustrated by what he perceives as Chinese backtracking or nonadherence to commitments he believes were made. Beijing, for its part, will continue to insist that certain provisions were never part of the formal understanding, emphasizing its own interpretation of the consensus.

The most significant source of potential friction may lie not in policy details but in worldview. In a recent Truth Social post, Trump described the United States and China as the “G2”, implying a partnership of equals responsible for steering the global economy and maintaining international stability. Beijing, however, has long rejected the “G2” concept. Xi’s public statements emphasize that China “has no intention to challenge or supplant anyone,” and that its focus remains on “managing China’s own affairs well.” In Beijing’s eyes, the G2 framing implies shared global responsibilities and expectations that China neither seeks nor welcomes.

This divergence reveals the core issue with the agreements reached in Busan: both countries may genuinely believe they have built a stable foundation for a cooperative relationship, yet they envision different versions of what that relationship entails. What appears, therefore, as mutual harmony on the surface may instead represent two complementary but fundamentally incompatible logics that may, over time, poison the relationship.