China’s approach to conflict mediation is characterized by what scholars call “quasi-mediation diplomacy,” in which Beijing emphasizes rhetoric and symbolic gestures while avoiding costly commitments. Recent cases show that China prefers strategic ambiguity and bureaucratic caution over assuming a high-profile mediator role.

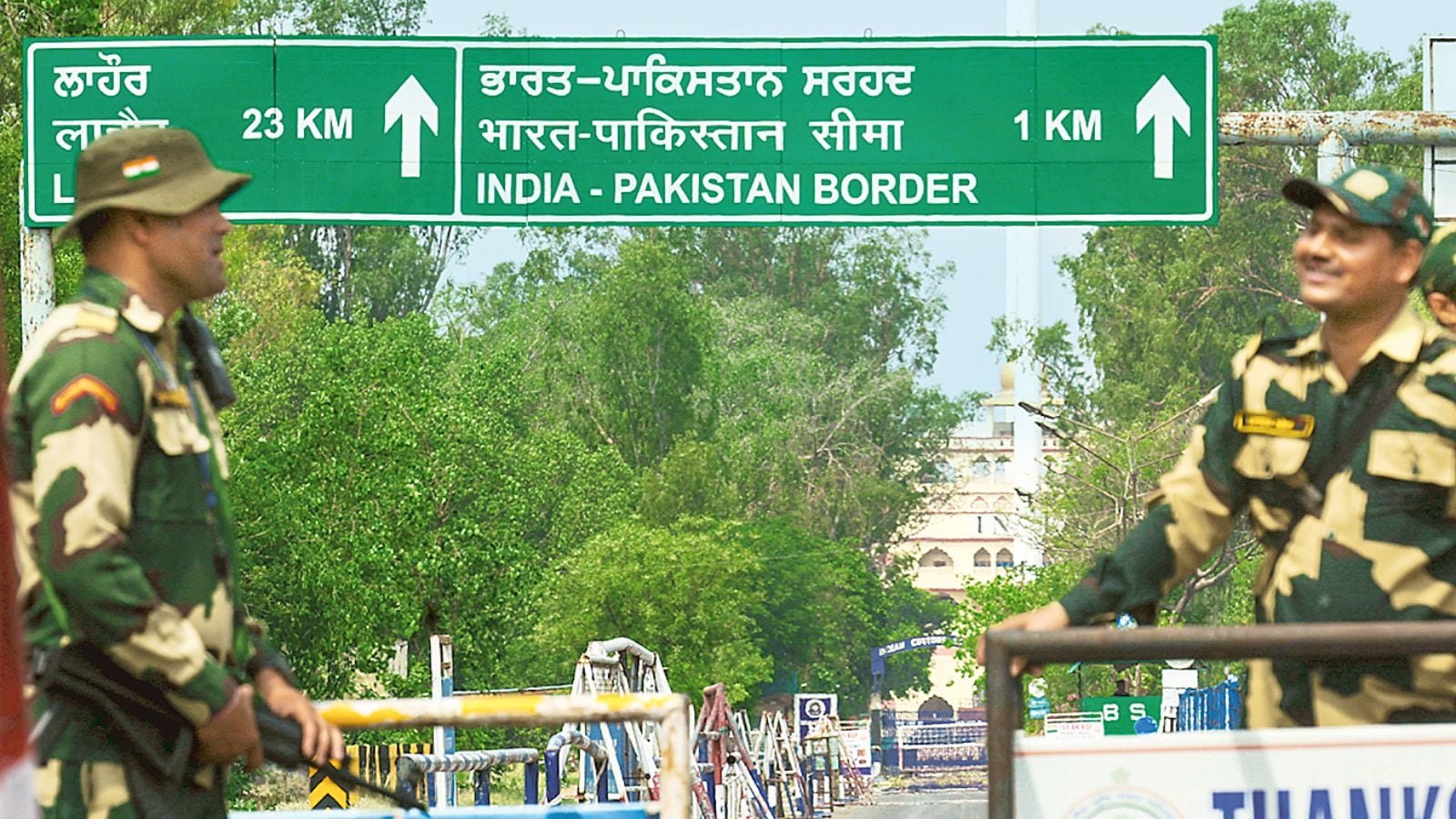

BSF personnel stand guard at the Integrated Check Post near Attari-Wagah border, in Amritsar district, Friday, May 2, 2025. (PTI Photo)

A terrorist attack on April 22nd, 2025 sparked one of the worst confrontations between India and Pakistan in recent years. The Indian authorities accused the Pakistani state of failure and potential complicity in the attack, and launched missile strikes on May 7th. Pakistan retaliated through an attack on Jammu, which was followed by a missile campaign from India, termed Operation Sindoor. On May 10th, both parties agreed to a ceasefire.

Whilst U.S. President Donald Trump has seized upon the opportunity to claim credit, others have observed that the extent of mutually inflicted damage and concerns over the manageability of the fall-out from the high-intensity conflict – at a time of much political fragility in the region – played a decisive role in pulling both sides back from further intensification.

Just over a month later, on May 28th, Thailand and Cambodia found themselves in a ten-minute skirmish along the border, resulting in the death of a Second Lieutenant from the Cambodian side. The Emerald Triangle clash in turn precipitated a series of escalatory gestures, culminating in a full-on armed conflict that broke out on July 23rd.

Once again, President Trump made haste to insert himself rhetorically into the conflict. He declared that “I am trying to simplify a complex situation!”, by threatening that he would “not want to make any Deal, with either Country”, unless they reached a ceasefire.

Arguably, Trump’s words might have played some role – albeit with the exact delta unclear – in nudging the leaderships of both ASEAN countries to accept the “immediate and unconditional ceasefire” announced in Kuala Lumpur on July 28th.

On the other side of Thailand lies Myanmar – a country long embroiled in a vicious, endless civil war. Its military junta government had recently declared the beginning of its purported “elections”. Peace appears elusive, as both the Tatmadaw and disparate rebel groups dig in their heels.

Whilst the presence of China loomed in the background across both conflicts, Beijing notably had been reticent in taking on a more high-profile and interventionist mantle in relation to all such conflicts. Chinese diplomats were doubtlessly involved to varying degrees with facilitating a modicum of communication between key stakeholders, yet they have notably eschewed the limelight externally and agenda-setting responsibilities within such dialogues.

China’s Quasi-Mediation Diplomacy?

Indeed, the three examples above comprise conflicts within China’s geographical neighbourhood. When it comes to more distant conflicts, such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the ongoing conflict in Gaza, Beijing has been even more reserved and lukewarm in terms of substantive actions; instead, it has opted for a largely rhetoric-powered construal of these events as demonstrative of Western hypocrisy – thereby turning such conflicts into rhetorical ammunition in its ongoing attempt to castigate the foreign policy of the amorphous “West”. The moral failure of the West is a powerful and conducive motif feeding into the leadership’s declaration that as the world experiences “great changes unseen in a century”, China must speak and stand up for the rest of the world, especially the Global South.

The term “quasi-mediation diplomacy” was employed by scholars Degang Sun and Yahia Zoubir in their 2018 article, to describe China’s action stratagem in relation to select international conflicts, aimed at defending “its commercial, political and diplomatic interests rather than core security and strategic interests”. They went on to posit that “this type of mediator acts without seeking to dominate; to follow rather than to lead”.

Yet what remains ambiguous throughout their analysis was the extent to which intention in fact matters under these descriptions. For one, what if mediating countries end up dominating without seeking to, or inadvertently compel others to follow, even if their intention is not to lead? Alternatively, what if there is an intention to dominate, shape, and set the agenda on the part of the mediators, but a dearth of actual capacity to do so? More fundamentally, must quasi-mediators act only out of commercial, political, and diplomatic considerations, or could there be weak strategic reasons that – whilst extant – are inadequate in overcoming natural inertia concerning mediation activities?

Drawing upon Guy Burton’s more recent assessment of China’s quasi-mediation efforts in the Middle East, I would propose an alternate definition of quasi-mediation: quasi-mediators are a) mediators insofar as they contribute towards expanding (but not creating) opportunity openings for conflict resolution between external actors; b) quasi- in the sense that they are heavily limited in the commitment (both in actuality and in threat) of resources – e.g. they may deploy copious volumes of rhetoric, including both formalistic gestures and informal speech, in amplifying the strategic incentives for conflict actors to come to the table. Yet they are unwilling – though not necessarily unable – to sink significantly more resources into the cause, as they have a relatively low-cost ceiling.

When it comes to China, there exists plenty of evidence for such behaviours. Across the four examples of the Cambodia-Thailand, India-Pakistan, Russian invasion of Ukraine, and Israel’s war in Gaza, Beijing has advanced emphatic statements laden with moralising undertones – commenting on the need for “peace” and the perils of “zero-sum” or “Cold War mentality” (especially over Ukraine). Yet it has not – as of writing – applied penalties or provided positive material benefits for actors who are willing to come to the negotiating table. Nor has it sought to position itself as a vigorous and forceful mediator tasked with the securing of regional peace.

Why the Reluctance?

Understanding why China is a reluctant quasi-mediator for most global conflicts – specifically ones in which it is not directly embroiled – behooves acknowledging the complexity of dynamics involved. There exists no single answer that can meaningfully address all instances. Indeed, what is far likelier, is that a combined tapestry of factors contribute collectively towards modern China’s diplomatic mores and tendencies.

One interpretation is that China lacks the requisite knowledge. As I noted in a recent interview, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) has long refrained from the more tempting – and dangerous – tendencies of its American counterpart to position itself as a de facto arbitrator of global affairs and upholder of regional security. MOFA diplomats may possess reasonable working understanding and insights into China’s bilateral relations with the various parties in the conflict yet some fear that they do not possess the nuance and contacts on the ground to get to grips with the ‘lay of the land’. The lack of accurate intel thereby precludes sharp, prompt, and bold moves aimed at securing peace.

This hypothesis may explain – to a certain extent – China’s wariness of wading into the Israel-Gaza or Russia-Ukraine conflicts yet does not hold much water in explaining China’s reluctance to partake in mediating conflicts within vicinity of its national boundaries. Through inter-party diplomacy conducted via the International Department of the Communist Party of China (ILD), public diplomacy via the MOFA and the United Work Front Department (UWFD), the Chinese state has long accumulated significant insights into how its surrounding countries and regions work.

Another hypothesis, then, is that China is wary of setting precedents for justifying foreign interventions into its domestic affairs – e.g. on questions pertaining to Taiwan, Xinjiang, and Tibet. The more it intervenes into other countries’ affairs, the reasoning goes, the more ammunition there is thus delivered to those who seek to play up domestic issues in China as a means of demonising – and instigating political changes on the ground in – China.

Yet Chinese leaders and diplomats are also increasingly cognisant that amidst the ratcheting-up of geopolitical tensions and great power rivalry between China and the U.S., both rhetorical and substantive attempts to interfere with China’s domestic sovereignty will continually be mounted. This trend will continue regardless of whether Beijing chooses to opine on other countries’ internal affairs. In any case, Beijing’s rhetoric alone, as well as its economic prowess, is often cited as evidence of China’s putting alleged pressure on other countries – and thus the worry about perceptual backlash is perhaps mis-placed: the cat’s already out of the bag.

China’s “Strategic Ambiguity” and Bureaucratic Risk-aversion

A far more plausible explanation contains two key components.

The first is that the Chinese leadership has long derived gains from strategic ambiguity of its own – for instance, in courting both India and Pakistan, in trading extensively with Thailand and Cambodia, and in playing “all sides” in the Myanmar civil war, the foreign policy establishment has sought to carefully navigate and manage its relations with and interests across a number of geopolitically disparate actors. When it comes to the ongoing border clash between Thailand and Cambodia, Beijing has considerably deepened security cooperation with Bangkok since the 2014 coup d'etat, and has long been Cambodia’s largest trading partner and source of foreign direct investment. As the cliché goes, “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

The second explanation requires a deeper examination of incentives within the Chinese political system. Mid-career diplomats in the Chinese foreign policy-making hierarchy are wary of incurring unnecessary risks, as they angle for promotion into the highly coveted circle of Organisation Department-administered cadres. These bureaucrats are also the ones tasked with communicating and offering substantive recommendations to the leadership through internal memos – ‘neican’ submissions. Bearing in mind the extreme levels of competition and generally high standards of party cadre (in levels of education, technical qualification, and political loyalty) within members of the Foreign Affairs System (now helmed by the Office of the Central Foreign Affairs Commission, and including both MOFA and ILD), there exists no room for error. If any of these upper-mid-ranking bureaucrats were to propose and endorse a mediation proposal that goes awry – whether it be due to the reticence to negotiate in good faith from both sides, unilateral violation of the ceasefire, or external interference – they would be viewed very harshly by their superiors, in a career where any single poorly handled decision could well be career-terminating.

As such, it is rational – from the perspective of career advancement – for diplomats to recommend the least risky course of action to their seniors, especially when it comes to the handling of high-stake conflict. Unless the senior Party leadership takes a robust and unconventional interest in mediating in conflicts, which overrides the natural institutional tendencies towards risk aversion, there exists little to no organic motivation for mid-ranking diplomats to back, of their own accord, ambitious and personally costly mediation proposals.

In short, rhetorically playing up mediation whilst refraining from substantive commitments to the process is not only aligned with China’s interests, but also the interests of integral decision-briefing bureaucrats responsible for bridging leadership with working-level cadres and the front-lines of conflict scenarios.