The fragile ceasefire in Gaza reflects accelerating recalibration in the Middle East, as U.S. military maneuvers are giving way to economic development promoted by the Arab states, China and the Global South.

People embrace following news of a new Gaza ceasefire deal, Oct. 9, 2025.

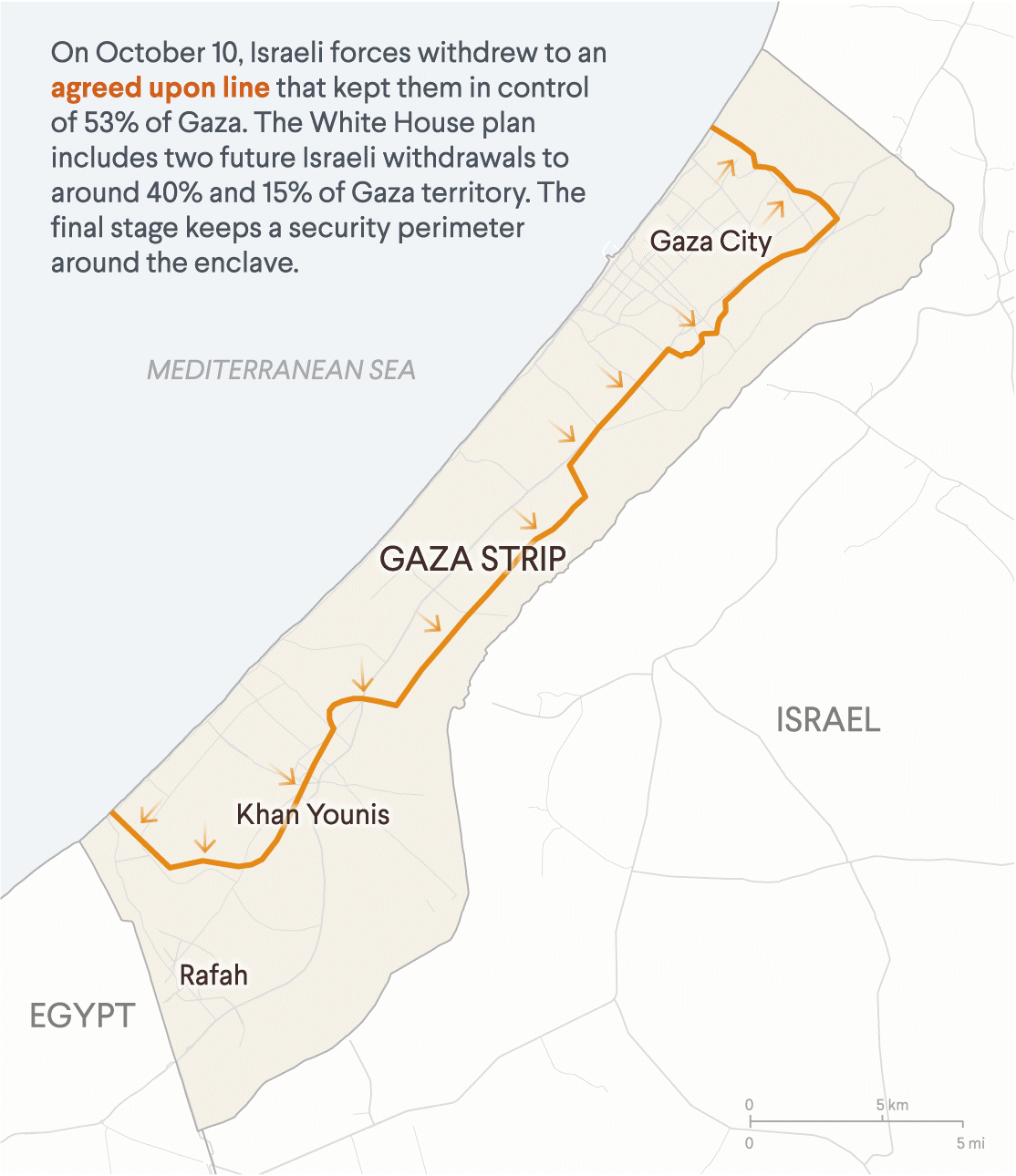

On October 9, when the Gaza ceasefire took effect, it was regarded as the first phase of a 20-point peace plan drafted by the White House. Neither Israel nor Hamas liked the full plan. But the former was pressured by Trump and the latter by a set of Arab states, particularly Qatar, Egypt and Turkey. That's what made the imposed ceasefire unique.

But it's no peace plan. It is a fragile ceasefire scheme that could be developed into something more lasting over time; or undermined like the previous ceasefire efforts.

It reflects major Arab states’ rebalancing in the broader Middle East as they seek a gradual shift from decades of destabilization to economic development.

From ceasefire to peace?

In the first phase of the peace plan, the two sides agreed to a set of parameters - including ceasefire, a military drawdown, a hostage and prisoner release, troop deployment and, most importantly, aid delivery increases.

Source: White House, CFR

https://www.instagram.com/p/DPxAxKLDAbg/

But the devil is in the implementation details. Infrastructure rehabilitation hasn't really started and inadequate food aid has left almost 2 million Palestinians in a dangerous limbo at the eve of winter.

What sold the Trump plan to Arab states was the stipulation that no Palestinians will be militarily forced to leave Gaza and that Israel will agree not to occupy or annex the Gaza Strip. To reach the aspirational goals, the plan offers little guidance, except for the formation of an International Stabilization Force; technocratic transitional governance by a Palestinian committee, under an international board chaired by Trump and led by the controversial former British Prime Minister Tony Blair; demilitarization by an independent monitor group; and economic reform by a panel of experts.

The plan doesn’t address the funding for reconstruction, which is estimated to cost more than $50 billion. That’s significantly less than the $68 billion Israel paid for its Gaza war in 2023-24 alone, with weapons and financing mainly by the U.S.

Drivers of regional instability

Since 1945, the U.S. hegemony in the Middle East has relied on oil buys, weapons sales, aid dependency and regime change. After his first term, President Trump has built on the Abraham Accords (2020-1); a series of bilateral agreements to normalize relations among Israel and Arab states, led by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Bahrain. With massive oil buys from and arms sales to Riyadh, the goal is to have Saudi Arabia join the Accords.

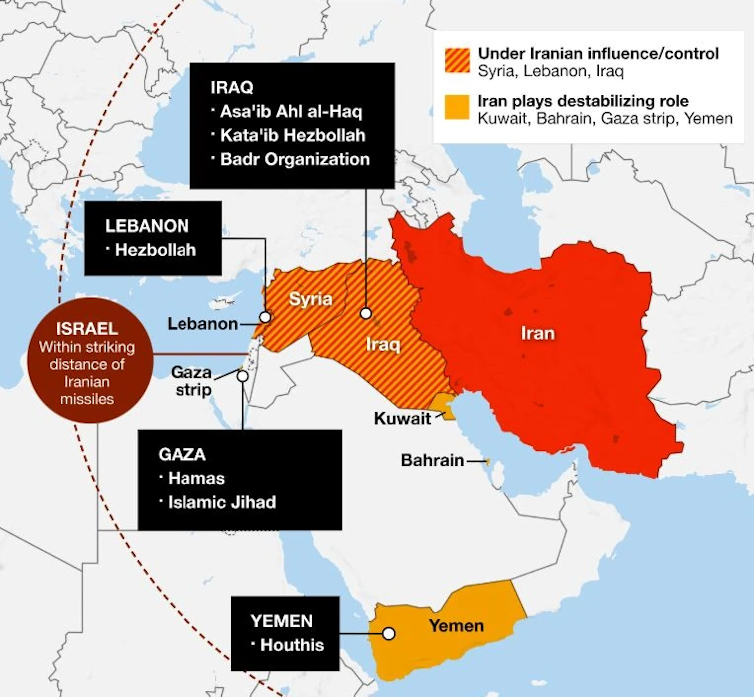

In the U.S.-Israeli view, Western interests in the region have been threatened by “Iran proxies” in Gaza (Hamas), Lebanon (Hezbollah), Yemen (Houthis), Iraq (various groups). Following the Gaza wars, they believe the Axis has been severely weakened.

Western view of Iran’s influence in the Middle East. (Source: Master Strategist/Axis of Resistance, CC BY-SA)

But here's the problem: this view effectively ignores a century of colonial interventions in the Middle East, Israel’s ethnic cleansing and forced population transfers (1948-49, 1967, 2023-25), U.S. sanctions (Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Yemen), U.S. efforts at regime change (e.g., Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Yemen, Gaza), and U.S. post-9/11 wars in the region (Iran, Iraq, Yemen).

The regional states attribute most of the destabilization in the region to Israel and the United States, due to the huge adverse spilloversto adjacent Arab states.

Rebalancing in the changing Middle East

Saudi Arabia has concerns both with U.S. disengagement from the region, which would undermine the Gulf countries’ current security arrangements, and with excessive U.S. engagement in the region, which is seen to foster Israel’s increasing military boldness and growing hegemony in the region.

As Riyadh is fostering its strategic autonomy and diversifying its partnerships, China has replaced Washington as the kingdom’s main trade partner. In parallel, major regional Arab states, including Egypt, Turkey and Gulf states, such as Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Bahrain, and Iran, build on the China-led Belt and Road Initiative.

Selling oil in multiple currencies, Saudi Arabia is one of China’s largest oil suppliers. It has been invited to join the BRICS, which features Egypt, Iran and UAE as its members. In fact, the Gulf-China trade and investment ties are now growing well beyond energy industries.

For decades, U.S. administrations fostered divides between Saudi Arabia and Iran. But in March 2023, these two countries resumed relations, after a China-brokered deal. The détente has proved resilient after October 7, shielding the kingdom from Iranian and Houthi attacks; most – if not all – of the time.

In August 2024, Beijing established a Second Silk Road in the region. In July 2025, China and Egypt expanded their bilateral cooperation across various economic sectors.

How Qatar attacks sped up recalibrations

On September 9, Israeli missiles slammed into an office in Qatar where Palestinian group Hamas’s top negotiators were discussing President Trump’s latest proposal for a ceasefire. Targeted assassinations have been an Israeli norm for decades. But this attack occurred on the soil of a major U.S. security partner, with no warning to Qatar.

Concerned that their peace efforts would go off the rails, Trump and his special envoy Steve Witkoff decided to try to turn the crisis to his advantage by initiating the talks that led to the ceasefire.

What the two did not see coming was the Saudi-Pakistani defense pact just two weeks later, between Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Prime Minister Muhammad Shehbaz Sharif. According to the pact, “any aggression against either country shall be considered an aggression against both.”

Afterwards, Pakistan’s Defense Minister Khawaja Mohammad Asif suggested that the pact included a nuclear umbrella. Subsequently, he retracted his comment.

Downplaying the pact and its long-term ramifications is in the U.S. interest. Yet, other sources say Pakistan has extended a nuclear umbrella to Saudi Arabia.

Eclipse of Israel’s nuclear primacy

Ironically, the nuclear stakes were first raised by the White House in June, with the U.S. attack against three major nuclear sites in Iran. But the U.S.-Israel path to nuclear risks in the region was paved already before the 1967 Six-Day War, when Prime Minister Levi Eshkol secretly ordered the nuclear reactor scientists in Dimona to assemble two crude nuclear devices, in case "Arab forces overwhelmed Israeli defenses.”

In the early days of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, PM Golda Meir’s cabinet had thirteen 20-kiloton atomic bombs assembled with greater destructive potential than the atom bomb in Hiroshima. In 1981, Israel destroyed Iraq’s nuclear reactor Osirak. The attack gave rise to the Begin nuclear doctrine, which allows no “hostile” regional state to possess nuclear military capability.

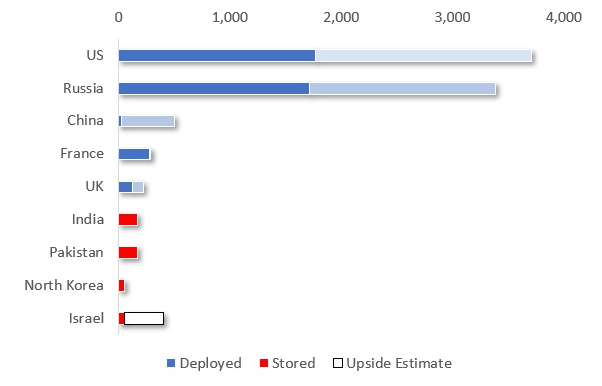

Today, the conventional estimate is that Israel’s nuclear stockpile comprises 90 nuclear warheads, which makes the tiny country the world’s 9th largest nuclear power (with 170 nuclear warheads Pakistan is 7th). Yet, some analysts suggest the Israeli figure could be as high as 200, up to 400 nuclear weapons.

World Nuclear Forces (Source: Author’s The Fall of Israel, 2024)

The Begin doctrine relies on Israel's nuclear monopoly as a regional deterrent. But with the Saudi-Pakistan pact, that doctrine is in limbo.

What Saudi Arabia wants

Until the Israeli and U.S. strikes on Iranian facilities, Saudi Arabia was said to benefit from mounting U.S. pressure on Iran and Israel’s weakening of Iran’s proxy network. But the Gulf countries believe excessive U.S. interventionism can be worse than U.S. disengagement. In Saudi view, a regional order dictated by Israel and enabled by the U.S. would leave inadequate room for a solid Saudi position.

The Saudis recognize their reliance on the U.S. for security, but they are leveraging ties with China and building increasingly on their national and regional Gulf interests. The Saudi-Pakistani defense pact reflects this quest for greater security independence, with Washington reportedly made aware of the agreement only after it was signed.

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s main priority is the huge modernization initiative Vision 2030. Its future hinges on the kingdom’s integration in the international economy, safety and security, to attract tourism and foreign investment driving innovation-led economic transformation.

The massive project requires the kind of peace and stability that Chinese investment fosters in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf. But it also is premised on the kind of regional balancing that Washington can no longer reinforce.