The Turnberry System is a way to replace the WTO-based postwar multilateral trading system with bilateral agreements. It marks a significant turning point in global trade rules and will profoundly impact the global trade landscape.

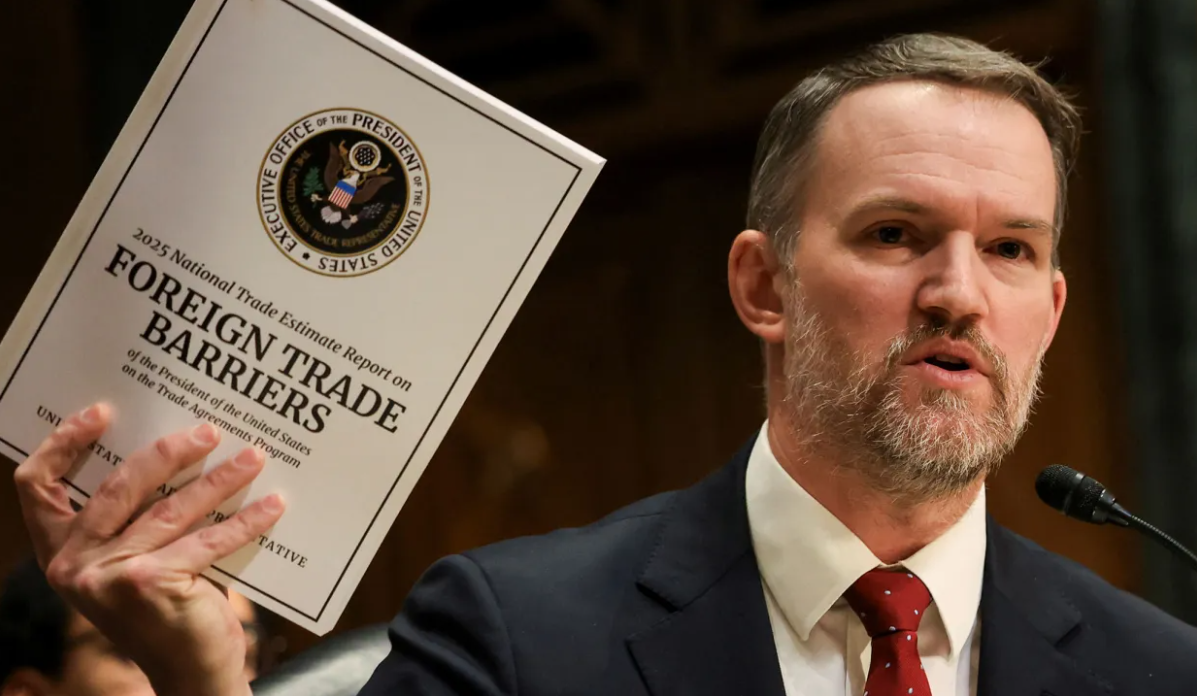

U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer holds a copy of Foreign Trade Barriers as he testifies before a Senate Finance Committee hearing on President Donald Trump's trade policy on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., April 8, 2025. (Photo: Kevin Mohatt/Reuters)

As trade policies under Trump 2.0 reshape the global economic order, the Turnberry System has emerged as Washington’s new economic and trade strategy framework.

The system originates from mid-summer talks between the U.S. and European leaders in Turnberry, Scotland. Commitments were made and public statements were made by U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer about the new strategic direction. In August, Greer declared that Washington was building a new trading system based on the core logic of “reciprocal tariffs.” It is an attempt to replace the long-standing postwar multilateral trading system based on WTO rules with a bilateral agreement mechanism, which represents a major shift in global trade rules and deeply affects the global trade landscape.

The strategic background of the Turnberry System is a reassessment by the United States of the global economic order. After World War II, Washington led the establishment of an order that was based on free trade, multilateralism and rules—ultimately contributing to the institutional expansion of the Bretton Woods System and the WTO. The fundamental logic was to exchange open markets and predictable rules for political influence and strategic security through a network of alliances during the Cold War.

However, post-Cold War globalization—especially the “hyper globalization” defined by the diffusion of global value chains since the 1990s—has impacted the U.S. economic and social structure. Industrial hollowing-out, supply chain migration, widening income inequality and rising industrial security risks ultimately led to political discontent, trade deficit pressures and strategic anxiety. Against this backdrop, in recent years, a consensus has gradually formed among some U.S. political elites that the original free trade narrative and institutional arrangements no longer serve U.S. strategic interests and are inadequate for coping with competition from rising powers.

A point that cannot be ignored is that U.S. policymakers believe that postwar multilateral mechanisms are ineffective in dealing with the rise of “state-capitalist economies” and industrial competition. Therefore, they attempt to use tariffs, export controls, investment screening and rules of origin as “re-institutionalization” tools, bypassing the constraints of multilateral governance to ensure that the international trading system serves U.S. industrial upgrading and geopolitical competition. Thus was born the Turnberry System. It is not merely an adjustment in trade policy; it is an institutionalization of the “America first” policy.

Currently, the system has three policy categories:

• the “reciprocal tariff” mechanism, which sets uniform tariffs or ceilings on goods from specific countries or industries;

• “selective market access,” requiring certain partners to open their markets to the U.S. through bilateral agreements in exchange for U.S. market concessions or tariff relief;

• “reconstruction of rules of origin," which indirectly raises barriers for foreign products and pushes overseas companies to localize investments in beneficiary countries by strengthening requirements on origin, rule compliance and supply chain traceability.

The combination of these tools creates trade policies with both explicit tariff barriers and numerous regulatory and compliance thresholds.

Greer claimed that the system aims to ensure true reciprocity between the U.S. and its trading partners. In other words, the tariffs the U.S. imposes on a country’s goods will be set with reference to the tariffs that country imposes on U.S. goods. However, this so-called reciprocity is entirely defined by Washington, which essentially leverages its powerful market to force other countries to accept its prescribed trade terms.

For example, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) is heading toward its first review in 2026. U.S. President Donald Trump has said he wants to renegotiate the deal, potentially splitting it into separate U.S.-Mexico and U.S.-Canada bilateral agreements or tightening rules of origin to increase U.S. benefits, to address the challenge posed by China’s global supply chain arrangements via Mexico. The USMCA contains a six-year review clause, which the U.S. views as a lever to apply pressure and amend arrangements it finds unfavorable. Under the Trump administration’s “America first” policy, any short-term victory beneficial to domestic manufacturing or labor has significant political value. By threatening withdrawal or shifting to bilateral negotiations, the administration can achieve a stronger negotiating position with Congress and domestic interest groups.

The Turnberry System poses a structural challenge to the postwar multilateral trading order. It operates by three major principles: non-discrimination (most-favored-nation treatment), tariff concessions/rule stability and a multilateral dispute settlement mechanism to ensure rule enforcement. The Turnberry System, however, severely undermines the cornerstones of the traditional order.

First, it constitutes a systematic disruption of the WTO multilateral mechanism. It directly violates core WTO principles, especially the most-favored-nation principle. Through agreements on tariff ceilings, rules of origin and specific partner exemption mechanisms, the U.S. applies differential treatment for different countries, granting allies market access advantages while erecting institutional barriers for non-partner countries. This marks the replacement of the universality of the multilateral system with access-based trade.

For instance, under the agreement, the EU applies zero tariffs on all U.S. industrial goods but does not grant the same preferential treatment to other WTO members. This is clear discrimination. Washington imposes a 15 percent tariff on most EU goods (far above the previous 2.5 percent MFN rate), but the EU is forced to accept this unequal arrangement in a major setback for the WTO’s non-discrimination principle. Further, the U.S. refuses to notify the WTO of the core content of its bilateral arrangements, rendering the WTO’s oversight and review mechanisms ineffective. Regarding the dispute settlement mechanism—and with the organization’s appellate body paralyzed by prolonged U.S. obstruction—the WTO can no longer effectively constrain Washington’s unilateral actions. Consequently, the member states have to accept its terms in agreements.

Second, the Turnberry System leads to the fragmentation of global trade rules. The system drives a shift in global trade rules from multilateralism to bilateralism, creating different versions of trade terms negotiated with different countries based on the “America first” concept. This shift leads to fragmented trade rules, which will increase global transaction costs and destabilize global supply chains.

Third, the system weakens the multilateral dispute settlement mechanism. The U.S. has long blocked the appointment of judges to the WTO appellate body, resulting in its functional paralysis. The Turnberry System further enables internal coordination between the U.S. and its partners to replace law-based multilateral dispute resolution, turning trade dispute settlement into political negotiation rather than legal adjudication. This will undermine legal neutrality, increase the institutional vulnerability of developing and small and medium-sized countries and make global trade rules more susceptible to geo-politicalization.

At a deeper level, the Turnberry System will undermine the nature of global trade governance as a public good. The United States is no longer providing broadly applicable public rules; instead, it is offering “limited public goods” to specific partners. This will not only change international economic relations but also alter power structures, signaling the transformation of the postwar order from a rules-based system designed to constrain power to one driven by competition in strength.