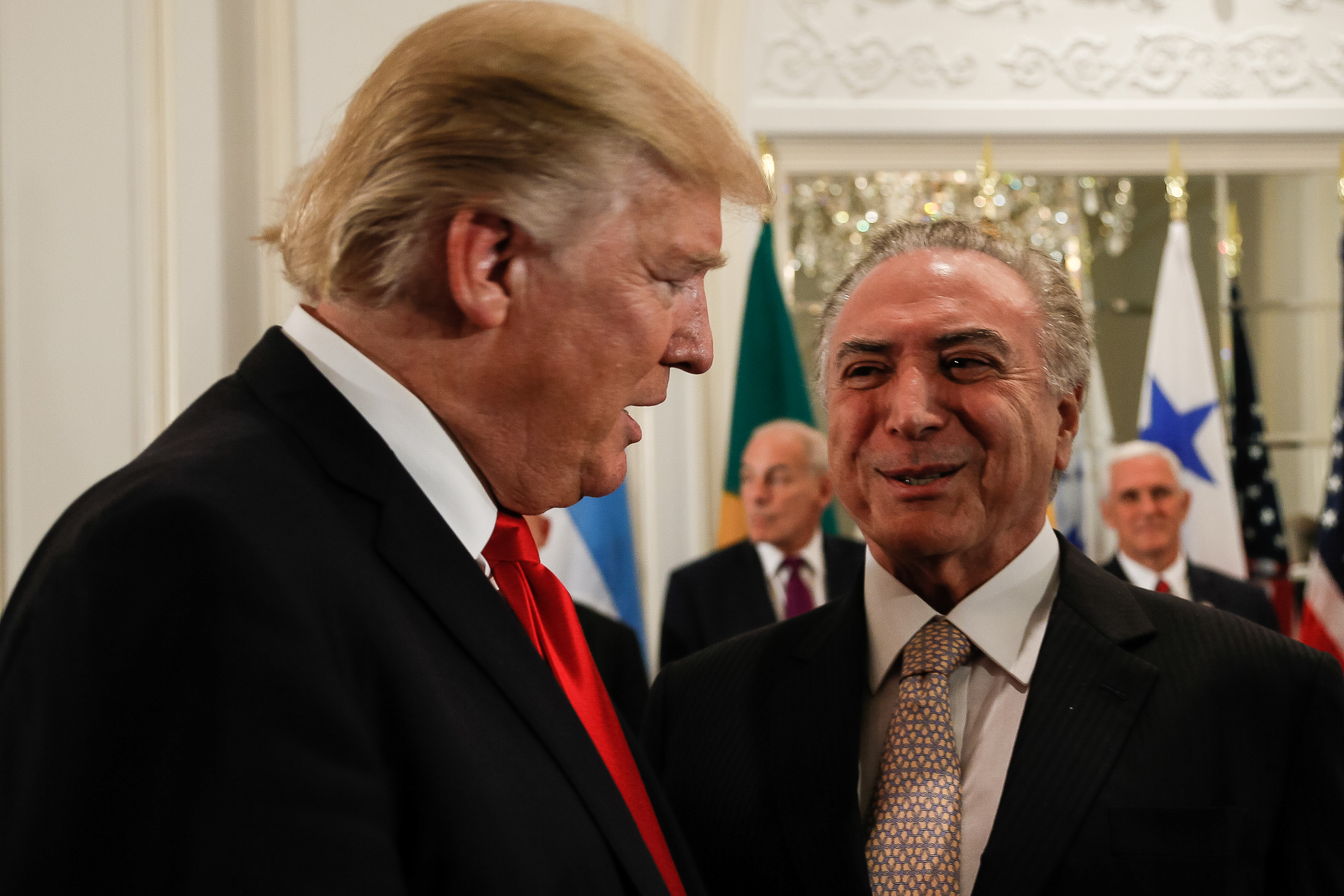

Donald Trump and Brazillian President Michel Temer

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s early February visit to Latin America and the Caribbean was impressive in ambition and scope. Beginning in Mexico and continuing on to Argentina, Peru, Colombia, and Jamaica, he made clear the United States’ long and abiding interest in working with regional partners and friends to strengthen democracy and support sustainable economic growth.

The headline from the visit was a tightened regional consensus on the need to address Venezuela’s growing humanitarian crisis, which is now affecting neighbors including Brazil, Colombia, and Guyana, and islands in the Caribbean, as refugees flee economic and social collapse. Indeed, shortly after Tillerson returned to Washington, the host of the April Summit of the Americas, Peruvian President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, formally rescinded the invitation for Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro to attend. Other regional steps including further sanctions may soon be announced as the effort intensifies to encourage the Government of Venezuela to change its destructive course.

Much less noticed, however, was the implication laid out in the Secretary’s speech at the University of Texas, just prior to departing for Mexico, that China’s continued inroads in the hemisphere are unhelpful for regional development and require that the United States become more diligent in its engagement with the region. The Secretary also hinted that China’s approach created the specter of new imperialism, which the region has long rejected, suggesting, for example, that, “Latin America does not need new imperial powers that seek only to benefit their own people.”

Official Chinese media angrily rejected these comments. Global Times wrote that, “Chinese people might be surprised to find out that their country is labeled a new imperial power…What did China do in Latin America?” Xinhua claimed the United States is “against any kind of multilateralism,” and highlighted interviews with academics and journalists dismissing the Secretary’s comments. Others expressed similar views.

Nonetheless, the Texas speech clearly identified a new U.S. approach to Latin America and the Caribbean, with a heighted focus on slowing China’s regional ambitions, consistent with the Trump Administration’s efforts to counter China globally. This is a shift. The Obama Administration was content with a laissez faire approach to regional issues, consciously diminishing the U.S. role in Latin America and the Caribbean while intentionally opening space for leadership to emerge from within the region itself. In the abstract, this was a worthwhile effort to build regional capacity and reduce historical dependence on the United States. However, the Obama Administration did not factor in the emerging role of China and Beijing’s increasingly opportunistic efforts to fill the resulting vacuum. The United States did not push Latin America and the Caribbean into China’s arms, but by pulling back, it created space for others to fill. This trend has now accelerated with the withdrawal of the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and strident efforts to renegotiate NAFTA, among other steps that the Trump Administration has taken after just one year in office.

Now, it appears that the United States seeks a course correction, and intends to compete more actively for a region that has tended to defer by default to Washington. The question is whether U.S. steps will be too little, too late, or whether Washington will be able to recapture the initiative in regional affairs.

The effort may be complicated by recent announcements by President Xi and also by Foreign Minister Wang that Latin American and Caribbean nations would be welcomed into the Belt and Road Initiative, more formally bringing some nations into China’s global infrastructure orbit, a development that has begun to ring alarm bells in the United States. There is no question that Latin America and the Caribbean require massive infrastructure investments, and China is as welcome to participate in developing regional infrastructure projects as anyone else. But the United States is particularly concerned that the Chinese investment model is state-led and therefore directed by government interests from Beijing, with the potential to increase Chinese government leverage within the region. Indeed, China has exercised such leverage from time to time already.

There is also a growing impression in Washington that Chinese largesse has facilitated the Venezuelan collapse. Although estimates vary as to the specific amount, Chinese loans to Venezuela in the 10s of billions of dollars—some estimates go to the $70 billion range—have allowed the regime to solidify its rule and push toward full authoritarianism while pursuing an unsustainable economic course, creating a full-blown humanitarian crisis. This is not to suggest that China desires Venezuela to be a failed state or even an authoritarian state, but rather that as a practical matter, China’s significant unqualified economic support has enabled these unintended results.

Bridging these gaps will require strategic enlightenment from both sides, and also a recognition that the current path could create unnecessary tensions. Washington and Beijing both have interests in the Western Hemisphere that neither is likely to abandon. What makes this a challenging moment is that these interests do not perfectly coincide. Therefore it will be important to identify those areas where accommodation can be reached.

It is in nobody’s interest that Venezuela collapse. It is in both U.S. and Chinese interests that Venezuelan oil continue to flow; indeed, that the rapid decline and mismanagement of the oil sector be reversed and output significantly increased. It is undeniable that this will not occur under Venezuela’s current government. It is therefore in both Washington’s and Beijing’s interests that there be a political transition in Venezuela to a more democratic, representative, sustainable government.

Much like the resolution of the brutal Central American wars from the 1980’s was facilitated by diligent bilateral diplomacy between Washington and Moscow, a similar approach today between Washington and Beijing could be considered. And by engaging meaningfully in such a dialogue, both bilaterally and at the United Nations, China will immediately change perceptions about its intentions in the Americas. Were it to do so, the payoff would be enormous. Indeed, competition is inevitable, but cooperation wherever possible will lead to even better, mutually rewarding results.