China’s deal with the EU to replace proposed electric vehicle tariffs with a price floor reflects a broader shift in Beijing’s economic and diplomatic strategy to ease trade frictions and rebuild ties with Europe and other U.S. allies amid uncertainty over U.S. leadership. The success of this outreach will depend on China’s ability to address persistent trade imbalances and geopolitical concerns, rather than assuming that tensions with Washington will automatically translate into closer alignment with Beijing.

Export of B10 electric cars to Europe. (Photo: Leapmotor)

On January 12th, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce declared that it had reached a deal with the European Union (EU) over electric vehicle exports to the bloc. The deal came as the historic culmination of protracted negotiations between both state and industry players across China and Europe, in reflection of the tendentious nature of the trade debate that had dominated the interactions between the world’s second and largest economies for the past three years.

The deal effectively cemented an overhaul of proposed European tariffs on Chinese vehicles, and their replacement with an effective price floor – mainland carmakers could only export to EU member states vehicles that exceed a stipulated price, though they and their trade partners would not be required to pay direct levies to member states, per tariffs.

Analysts have quickly chimed in with their various assessments. Whilst these firms’ market shares would be dented in the short term, the intervention could well prove constructive in deterring Chinese vehicle makers from partaking in a mutually destructive spiral of price wars and aggressive undercutting – thereby enhancing their margins in the long run.

Yet what such commentaries overlook, as I pointed out last September, is the fact that Beijing’s openness to such a concession, perhaps unthinkable only a few years ago, speak to a much wider “anti-involution” campaign it has sought to advance, which also possesses a distinctive foreign policy dimension.

For long, European capitals have registered significant grievances towards what they perceive to be “unfair subsidies” and protectionism embraced by the Chinese authorities. The bruised Chinese administration in turn accused the EU of imposing discriminatory “trade and investment barriers” on Chinese capital. Neither side was particularly happy with the other’s alleged trade weaponisation. Of course, the feeling was mutual.

The winds of change are nevertheless blowing wild and free – not only in China’s relationship with the EU, but also the former’s relationship with some of the states conventionally and widely viewed to be strongly committed allies of the U.S. The King of Spain Felipe VI, accompanied by two ministers, visited Beijing in November. A month later, the French President Emmanuel Macron followed suit – and was met with rapturous applause on his tour in southwestern China.

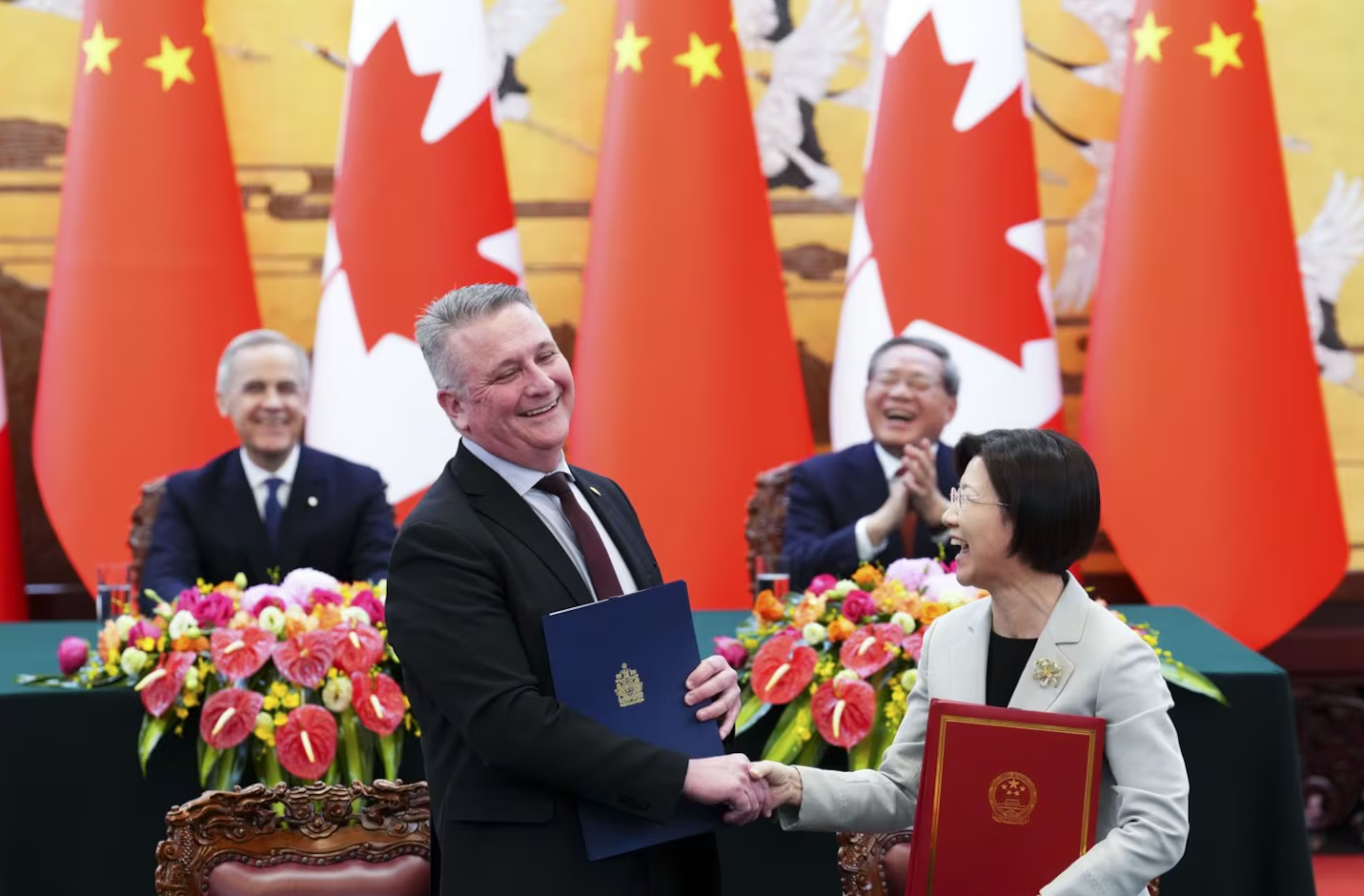

Days after the EU’s announcement, Canadian leader Mark Carney paid a historic visit to Beijing – the first trip by a sitting prime minister in nine years. Chinese President Xi Jinping hailed the past few months of “turnaround” in bilateral relations, with both sides seeking to ease mutual trade and investment restrictions; officials have dubbed the meeting “consequential and historic”. With his emphasis upon reorienting Canadian foreign policy to a “new world order”, Carney made very clear Ottawa’s fundamental opposition to the erratic cajoling and demands laid at its feet by its southern neighbour.

Canadian Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food Heath MacDonald and Sun Meijun, Minister of the General Administration of Customs in China, take part in a signing ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China on Jan 15, 2026.

Decoding China’s outreach efforts

The trend appears clear: since Donald Trump’s return to the White House last year, senior technocrats and politicians in Beijing have been adamantly seeking to rebuild China’s frayed relations, as well as deepening ties, with the Global North. Included in the mix are long-standing American partners – Canada, Australia, Western European states, and even the United Kingdom (notwithstanding the chaos unfolding on the domestic level).

This intentional strategic play by Chinese leaders is predicated upon the view that Trump’s self-serving, oscillating foreign policy would only drive allies and partners away from the U.S., and that China would be seen as a more palatable, stable, and capable collaborator amidst the global fracturing and regional rerouting of supply chains.

To a large extent, Beijing’s diagnosis and prognosis are not without their merits. Primarily, it became increasingly apparent that the assumption that China was the only country from which de-risking was imperative – an assertion that Sebastian Contin Trillo-Figueroa and I contested in October 2023 – simply cannot hold. The latest National Security Strategy from the U.S. revealed a vindictive Trump leadership bent on supporting ultra-conservative, MAGA-aligned movements (and even politicians) in Europe, as well as an eerie framing of the transatlantic relationship through the lenses of a cultural and ideological war. Washington’s harsh tariffs on European goods – coupled with the second-order effects of uncertainty arising from the repeated prevarications on issues ranging from Ukraine to Greenland – have only compounded the anxieties of European policymakers.

On the other hand, Europe is also coming to the realisation that writing off China’s potential – and equating de-risking with a rhetorically trenchant yet structurally uncoordinated response to China’s emerging technological prowess – quite simply cannot cut it. The spate of deeply cynical, almost eschatological assessments of the Chinese economy over the past decade had resulted in many observers in the West over-indexing the country’s macro headwinds – which certainly exist – and ignoring the tailwinds.

The former includes the chronic deficiencies in consumption, the property slump, and retrenchment amidst businesses that had struggled to emerge from “Long COVID”; yet there exists plenty of hope and opportunity to be sought amongst the latter – including the country’s impressive advancements in advanced manufacturing and ongoing efforts aimed at closing the urban-rural gap and ameliorating wealth inequalities.

As such, Chinese policymakers are correct in identifying an opening in Trump’s return to the White House, as well as the possible foreign policy dividends arising from their focusing on economic stabilisation. Where ideology and values fall short or increasingly drift apart, market access and business interests can and do come to the rescue.

The dangers of counting one’s chickens before they hatch

Yet Chinese leaders would do well in remembering the dangers of taking things for granted in geopolitics. Just as it would be hubristic for American policymakers to see the EU as an inherently weak, unsalvageable bloc of bureaucratic mess, it would be erroneous for Chinese to assume that antipathy and wariness towards Washington would automatically translate to affinity and openness to the Chinese.

Two key obstacles remain. The first concerns addressing the substantial trade deficits that most major economies share with China. Whilst the juggernaut’s formidable edge in advanced manufacturing is undeniably palpable, many around the world – in both emerging and mature markets – are increasingly apprehensive of the double whammy of over-dependence upon the Chinese, as well as their own firms’ being outcompeted by technologically superior and cheaper competitors from China. European and Anglophone governments, grappling with surging populism and business wariness towards the perceived flooding of Chinese goods in domestic markets, would most definitely appreciate more clarity – and strategic empathy – from Beijing.

The recent appreciation in the RMB is a positive step – it speaks to the cognisance of the Chinese leadership of the undesirable perceptual backlash it has and would continue to experience at the hands of resentful actors within its leading trade partners. Yet more must be done. Indeed, China needs an import policy – namely, the devising of a comprehensive, multi-faceted, and dynamic plan that would see to its importing an increased volume of goods from its trading partners, which would enable it to accordingly unlock one of the greatest points of leverage available to the American state: access to its immense markets.

The second challenge concerns geopolitical uncertainty. Be that as it may that the purported 2027 deadline has been grossly distorted and exaggerated by select Sino-skeptical voices on Capitol Hill as a means of securing additional funding for their pet defense projects, the persistence of speculative anxieties and undue scaremongering over the Taiwan Strait is an issue that the Chinese leadership must tackle head-on, if it is to meaningfully improve relations with a majority of European and Anglophone states, as well as preventing “de-risk” preoccupations from derailing its burgeoning economic re-engagement efforts.

Doing so in a way that maintains its baseline position and long-standing commitment to a posture of deterrence through strength – not war – would require much strategic acumen, tactical composure, and communicative efficacy on the part of Beijing.