In a recent speech, Canada’s Prime Minister Mark Carney declared the end of the rules-based order. Yet, U.S. unilateralism began accelerating in the 1980s, and much of the West complied so long as it remained beneficial. Today, that alignment no longer holds.

Recently, Prime Minister Mark Carney — perhaps the ultimate liberal insider — gave a seminal speech at Davos, declaring the demise of the rules-based international order and ushering in a new period of might-based diplomacy.

But there are cracks in this mainstream narrative. The U.S.-led rules-based order did not end in Davos. It has been fictional since the 1980s.

Rules-based order vs international law

The rules-based order was established by the U.S. and its allies after 1945. It comprised treaties, norms, practices, institutions, and power-backed expectations. Its key transnational components featured the well-known multilateral institutions from the postwar Bretton Woods system to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

In theory, its rules applied universally. In practice, the U.S. retained exceptional privileges, including sanctions, extraterritorial law, and military intervention. Ostensibly universal, it was rules-based order of, by and for America.

From the start, this order was challenged by the quest for international law. As opposed to unilateral power politics, the Global South and many small states saw international law as a consensual legal system among sovereign equals, rooted not just in treaties, but customary law and the principles of the UN Charter. That was their dream, an international order based on law.

These foundational principles included sovereign equality, non-intervention, territorial integrity, peaceful dispute resolution and prohibition on use of force. The only exception — self-defense or UN Security Council authorization — confirmed the rule.

Through much of the Cold War, the rules-based order and international law seemed to be largely aligned, though mainly within the Western bloc. UN Charter norms worked because U.S. interests were still broadly aligned with system stability, thanks to Soviet constraints which contributed to mutual restraint.

But the reverse applied as well. With the implosion of the Soviet Union, UN-style multilateralism no longer served a purpose in Washington.

The rise and fall of multilateralism

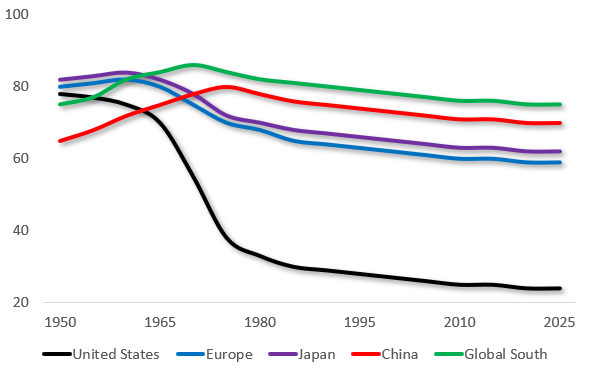

Let’s use the UN voting alignment as a proxy for normative unity, defined by how often states vote with the international majority in the UN General Assembly. The higher this alignment is, the greater is the integration into multilateral consensus, and vice versa. Conversely, low alignment suggests normative divergence or unilateral positioning.

Since the creation of the UN, the Global South has demonstrated the highest alignment for most of the period, peaking at mid-80s% in 1970 and hovering around mid-70s% today.

Starting from a lower point (65%), Chinese trajectory mimics that of the Global South. It rose into UN norms during the reform era, peaked at 80% in 1980 and stabilized at 70%-75% today. China is neither UN rule-breaker nor U.S.-like unipolar rule-maker.

Usually, the U.S., Europe and Japan are often lumped together as the “West.” But in light of the UN voting, this is flawed. Their convergence lasted barely a decade or two.

Since the 1960s, Europe and Japan have largely moved in tandem. They have not upheld the tenets of international law as strongly as the Global South and China. But nor have they emulated the U.S. trajectory. The voting patterns of Europe and Japan are far closer to those of China and the Global South. They profess legalism.

UNGA Voting Alignment (% with Majority)

Source: Data from UN

America First rules

The great anomaly among all major advanced economies worldwide has been the United States. After Washington built its rules-based order in the 1950s, it began to diverge from the multilateral tenets of that order. The steep decline has prevailed.

By the 2000s, the U.S. was the outlier of the international community. It does not seek the international law, multilateralism and universalism of China or the Global South. Nor does its penchant for unilateral domination have much in common with Europe and Japan, its key allies.

There was always a latent rupture at the heart of the rules-based order. In international law, states are formally equal. In practice, they never were. In the rules-based order, there was always a hierarchy between great powers and small states.

Selective legality weighed heavily in the rules-based order, as evidenced by many examples, including humanitarian intervention without the UNSC mandate (Kosovo, 1999); an illegal war framed as rule-enforcing (Iraq, 2003); sanctions regimes that are unilateral, extraterritorial and lethal, yet not UNSC-approved; and the International Criminal Court (ICC) in which the U.S. promotes accountability, but rejects jurisdiction over itself, particularly its military interventions.

Unsurprisingly, in the Global South, the rules-based order has long been seen as a hypocritical double standard: “rules for others, flexibility for the rule-maker.”

The divergence between the rules-based order and international law escalated dramatically during the “unipolar moment” of the post-Cold War decade, when the U.S. moved from law-constrained leadership to discretionary enforcement. Indeed, America First exceptionalism far predates the Trump administrations, which reject all semblance of multilateral pretense. Sanctions are a case in point.

From UN multilateralism to U.S. unilateral sanctions

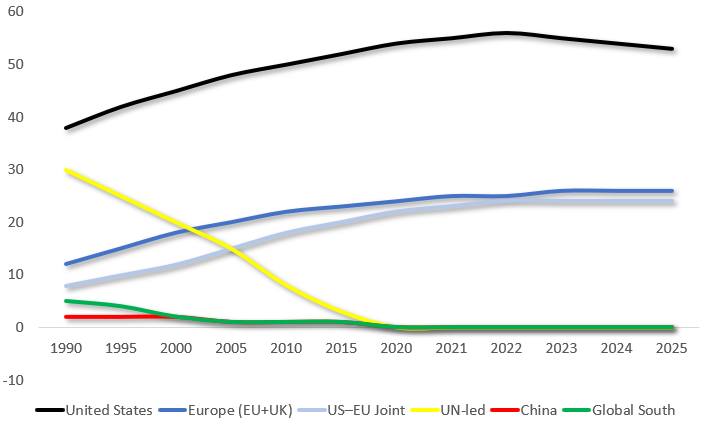

As unilateral coercive measures, American sanctions exemplify its unipolar aspirations. Since the end of the Cold War, their use has soared, thanks to technology (which allows targeting) and the erosion of multilateral legitimacy (which no longer constrains unilateral coercive measures).

Through the Cold War, a third of the sanctions were mandated by the UN and its multilateral consensus. The US accounted for about two-fifths of all sanctions. The rest could be attributed to Europe and joint US-Europe.

The West sanctioned the Global South. It was the old colonial dependency relationship déjà vu.

By contrast, the role of China and Global South in the sanctions amounted to a fraction.

In the post-Cold War era, UN-mandated multilateral sanctions have plunged from 30% to near zero of the total. Whereas U.S. unilateral sanctions have soared from 38% to mid-50s%. Meanwhile, Europe’s share has doubled to 26% and US-Europe joint sanctions have tripled to 24%. By contrast, those of China and the Global South remain minimal to non-existent.

Sanctions Structure (% of active sanctions regimes)

Source: Data from UN

Unilateral or Western-led sanctions (U.S. and EU sanctions) have become common tools. Many are not UN-mandated Security Council measures, raising questions about selectivity versus international legal authorization.

In the view of the Global South, unilateral sanctions are contrary to the UN Charter and international law, especially when used without broad multilateral approval and perceived as coercive.

The last nail

At Davos, Canada’s PM Carney declared at Davos “a rupture in the world order, the end of a pleasant fiction and the beginning of a harsh reality, where geopolitics, where the large, main power, geopolitics, is submitted to no limits, no constraints.”

It was a compelling speech that reflected the views of many in the West. But this rupture is not recent.

The world of brutal great power rivalry goes back to capitalist modernity and lethal colonialism in the 19th century. In that world, it has always been the case that “the strong can do what they can, and the weak must suffer what they must” – as a century of colonial humiliation taught to China and the Global South.

The not-so-pleasant fiction of the U.S.-led rules-based world has faded away since the 1970s. For almost half a century, U.S. allies benefited from its material perks. When they no longer didn't, Carney hammered the last nail into its rusty coffin.