French President Emmanuel Macron’s recent visit to China reinforced bilateral ties through trade, investment, and scientific cooperation, yet yielded few breakthroughs on contentious issues like Ukraine or advanced technology transfer, reflecting Beijing’s guarded approach. While Macron projects a Neo-Gaullist vision of strategic autonomy and a “Third Way” between the U.S. and China, structural constraints in France and the enduring weight of trans-Atlantic ties limit the substantive impact of his approach.

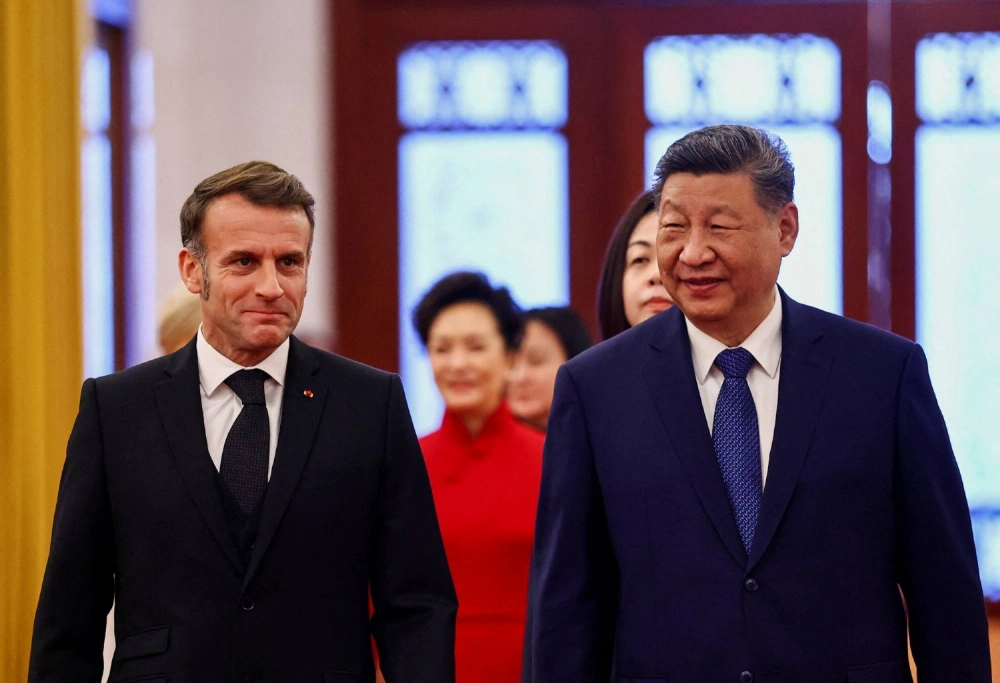

French President Emmanuel Macron walks with Chinese President Xi Jinping during an official welcome ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on December 4th as part of a three-day visit to China. (Reuters)

Last December, French President Emmanuel Macron visited Beijing – his fourth visit to the country. His trip took him to Beijing and Chengdu, in the latter of which his Chinese counterpart, President Xi Jinping, took the rare move of hosting and greeting a foreign dignitary in a city outside the capital.

State-affiliated media were effusive in praise about the meeting. China Daily heralded Macron’s visit for “strengthen[ing] ties, boost[ing] cooperation on global issues”. Another article spoke of the key drive for trade to “deepen Sino-French ties”. Xi himself commended France as an “indispensable economic and trade partner” to China – language increasingly rarely employed for members of the Global North in Chinese political discourse, given the growing fissures. Twelve agreements were signed on a plethora of topics, from nuclear energy to panda conservation.

Macron’s Neo-Gaullist Tendencies

Yet few major breakthroughs came on the fronts of the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, as well as the gargantuan trade deficit between Europe and China – both major agenda items that Brussels had become precipitously concerned by in recent years, and for which Macron effectively served as a channel of European concerns. Senior Chinese leaders reiterated their long-standing position of “support[ing…] all efforts to reach ceasefire and to restore peace in Ukraine”, without committing to further substantive concessions.

My learned friend Sebastian Contin Trillo-Figueroa has proposed the notion of orbital bipolarity; using that metaphor, one could argue that Macron has sought to make himself a welcome envoy to both poles, orbiting them on roughly the same frequency – with the hope that he can maximise upsides for his country and own political legacy.

Reciprocally, in Beijing’s eyes, France plays the abstract yet strategically significant role of embodying an alternative beyond the Sino-American binary – a possible zone and nexus of neutrality amidst the volatile and antagonistic bilateral dynamic between China and the US.

The French President and his inner circles clearly welcome such symbolic affirmation. Indeed, his tactical positioning reflects his long-standing ideological commitments in foreign policy. his official presidential photograph depicted him alongside French and European Union flags, as well as the memoirs of Charles de Gaulle, the defiant leader of Free France during World War 2 and a Founding Father of the Fifth Republic.

Ever the maverick, De Gaulle demanded equal standing with the US and Britain in NATO at the onset of the Cold War, and opted to withdraw his country from NATO’s integrated military command structure in 1966. He advocated that Europe should serve Europeans – as opposed to Americans, the Soviets, or any other interest bloc.

De Gaulle held high hopes for his own country as a vital pillar of the post-World War 2 international order, backed by a determined sense of strategic autonomy. Unity through organic alignment – not top-down control or a centralised bureaucracy like the US – epitomised his vision of European rejuvenation.

Yet almost six decades on from De Gaulle’s fateful decision to question the might of the US-UK axis in NATO, is Macron able to renew – and accomplish – what his predecessor had sought France to be? Or is his channelling of Gaullist thought performative and rhetorical at best?

To answer this crucial ask, two preliminary questions must be addressed.

What Can France Meaningfully Gain from China?

The textbook benefits for France from Sino-French economic cooperation are long-litigated: Chinese investment and capital into France, the continued opening-up of French markets for Chinese exporters, and deepening of scientific, technological, and human capital-driven ties (with highly securitised domains of advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence and semiconductors, being notable exceptions, given pressure from the “de-risking”-minded Brussels and Washington).

Yet are any of these benefits capable of addressing the most pressing domestic structural malaise confronting France today?

This fundamental worry concerns France’s declining labour productivity – which some have estimated to have amounted to declining by 8.5% between 2019 and 2024. Much of this could be attributed to the shift towards lower-productivity service sectors amongst the workforce, dearth of investment and substantive deregulation over new technologies, and weak research and development beyond a few select bright spots, such as aerospace technology and artificial intelligence.

Across a number of key domains, Chinese companies have now overtaken their French counterparts in technological (albeit not necessarily overall) productivity. In reflection of such sentiments, during his visit, Macron vocally urged leading Chinese companies to contemplate voluntarily transferring, or sharing, their tech expertise to French counterparts.

His relatively subdued tones contrast sharply with the more aggressive approach embraced by Brussels bureaucrats, who have stipulated that tech transfer could well be amongst the binding pre-conditions for Chinese investments into Europe.

Yet policymakers in Beijing have long been guarded about cutting-edge technologies – viewing breakthroughs in advanced manufacturing and artificial intelligence as matters of comprehensive (national, but also development and economic) security. The recommendations for the Fifteenth Five Plan herald a doubling down on industrial policies – with incorporation of bottom-up entrepreneurship and private capital – for nascent sectors such as food and agricultural technology, robotics, and space and aeronautical sciences (the latter, however, is a domain where both China and France could stand to gain from working together).

Whilst the Sino-American rivalry has momentarily receded in volume and apparent intensity, Chinese leaders remain alarmed by the prospects of being kneecapped by powerful, Western counterparts, with Washington leading the charge. Until – or unless – the Élysée Palace can demonstrate that its decision-making can be sufficiently independent from American influences, especially in areas of technology and supply chains, there exists limited to no motivation on Beijing’s part to significantly relax access to the core of cutting-edge technologies in its European operations.

With that said, the fifth priority in the 15th Five Year Plan recommendations – “expanding high-level opening-up” – does offer some consolation for French companies hoping to secure better market access into China. However, the realisation of this objective in practice would behove the introduction of more transparent, robust, and internationally acknowledged legal standards – in especially areas of arbitration, mediation, and commercial litigation – into the Chinese mainland; it would also require provincial and local governments to be more mindful of international sensitivities over data, personnel, and commercial practices. There remains a long way to go.

Can France Resist the Trans-Atlantic Itch?

It would be erroneous to see China as the only, or primary, obstacle to Macron’s Neo-Gaullist vision. A no less significant challenge comes from the other side of the Atlantic, with the Washington establishment long lambasting Paris over its perceived vacillations and mercurial stance on Russia, China, and, indeed, the Middle East. Strategic autonomy in one’s eyes could be annoying perfidy in another, and perfidy comes with a price.

The ties between Paris and Washington are undeniable – NATO remains the key backbone of French security, through interoperable defence and joint exercise-based training; American and French intelligence services are closely linked, not just through the CIA-DGSE connection. Financially, the US is the main foreign investor in France, contributing 17% towards the 2023 foreign investment total in the country.

With Congress hawks blasting the Trump administration over alleged capitulation in its granting Nvidia the greenlight to sell advanced H200 AI chips to China (in exchange for a handsome cut of the profit), two conclusions are apparent: first, establishment hawks wary of Macron’s Neo-Gaullist project may be facing a greater threat from within – the undercurrents and individuals who set the tone for the recently unveiled National Security Strategy; second, and on the other hand, Trump’s quest for a more “hands-off” and less directly confrontational Indo-Pacific strategy could well be undermined by an obstinate lobbying bloc of China sceptics within Congress, but also the chorus of neo-conservatives in his cabinet, leveraging the apparent successes of Trump’s authorised operations in Venezuela earlier this month.

How this tussle plays out, not only has a decisive role in shaping the behaviours of American foreign policy actors, but also in indirectly constraining and shaping the range of options available to Paris. The more Washington eases its campaign to inhibit China’s economic and technological developments or rising influence in multilateral institutions, the more appetite and wiggle room there is in Paris has in pursuing the “Third Way”. The converse may not necessarily hold true – Macron should bear in mind the peril of hubris.