With U.S. encouragement, Northeast Asia has seen unprecedented cooperation between Japan and South Korea in recent years. But rising economic frictions, domestic political changes in Japan and especially South Korea, and evolving U.S. global priorities could impede or even reverse recent gains.

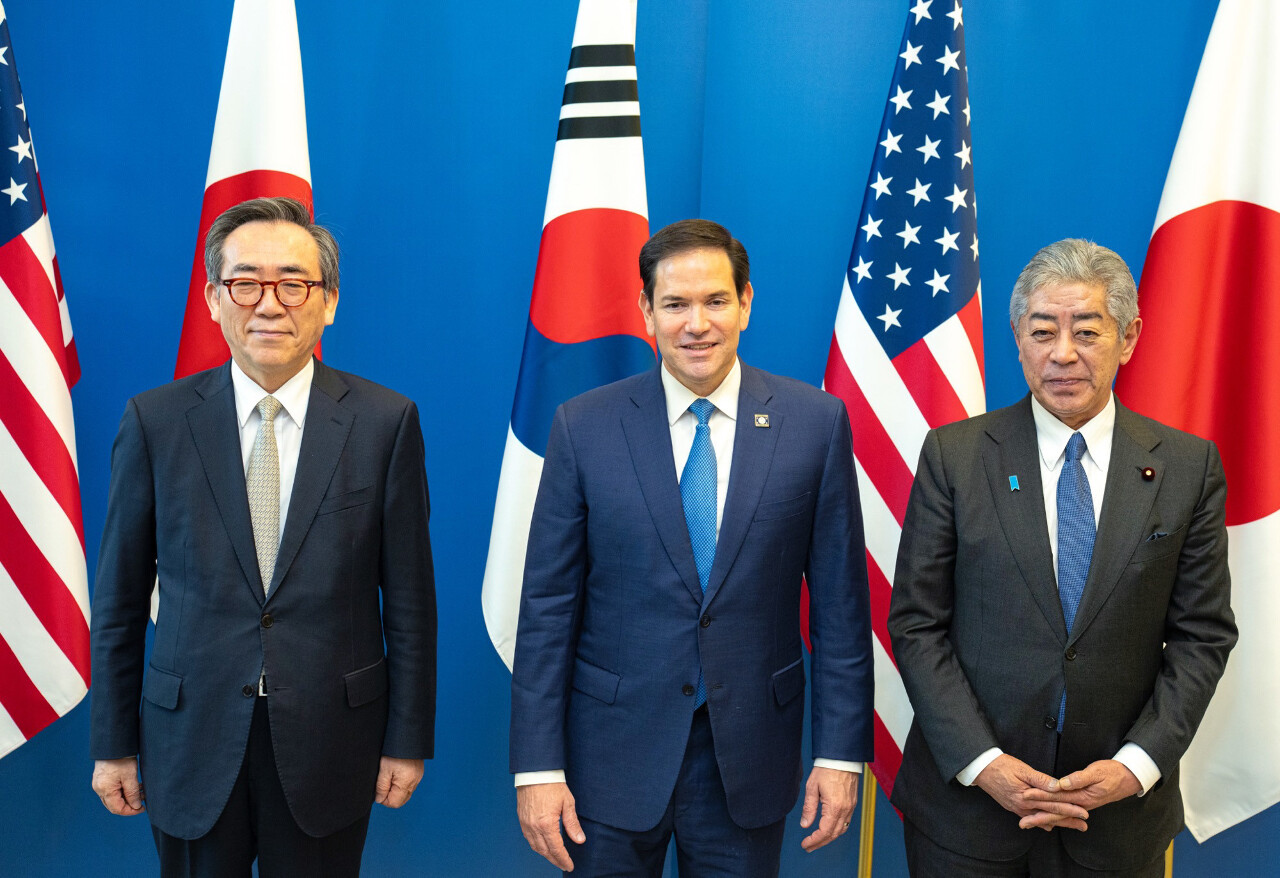

(from R) Japanese Foreign Minister Takeshi Iwaya, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio and South Korean Foreign Minister Cho Tae Yul meet in Brussels on April 3, 2025. (Photo: Kyodo)

Japanese-South Korean relations have waxed and waned throughout history. They have experienced a remarkable upswing in recent years, to the benefit of the United States and other countries. But now we stand at a precipice. Whether Japan, South Korea, and the United States will continue to improve relations, strengthen ties even further, or regress to previous problems should become clearer in the coming months.

During the past few years, the three national governments have made remarkable progress in surmounting decades of halting progress toward strengthened ties. Whereas the initial focus of the three countries’ trilateral collaboration was on managing North Korea’s security provocations, Japan, the Republic of Korea (ROK), and the United States recently have substantially broadened their collaboration’s geographic and functional expanse.

Some driving forces behind this improvement have included Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine (which abruptly elevated all three governments’ concerns about the risks of military aggression in Asia); the solidifying authoritarian axis of Russia, China, and North Korea (which furthered a sense of solidarity among democratic leaders); and the resolute commitments of President Joe Biden, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, and South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol to a comprehensive trilateral partnership.

A primary goal of the three governments, highlighted by their August 2023 Camp David summit, was to make their trilateral partnership more robust and enduring by institutionalizing their cooperation. At the summit, they pledged to hold annual multi-domain trilateral exercises, exchange real-time data on DPRK missile launches, and pursue enhanced ballistic missile defense cooperation. Then South Korean National Defense Minister Shin Wonsik, who was the first ROK defense minister to visit Japan in 15 years, said these kinds of measures aimed to make their defense cooperation “irreversible.” Beyond defense issues, the three governments committed to consult with each other on other common concerns and to collaborate on international development, global governance, sanctions and high-tech export controls, and Taiwan-related scenarios.

A hybrid conference hosted by the Asan Policy Institute on April 23 highlighted this cooperation. The speakers noted that the weakening of global norms, rules, and institutions, such as the United Nations, has made smaller group mini-lateral cooperation, exemplified by the ROK-Japan-U.S. partnership, even more important. This partnership, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, the Australia-UK-US (AUKUS) defense industrial pact, and other regional cooperation projects help the Indo-Pacific democracies compensate for the absence of EU- or NATO-like institutions in Asia. Even so, the speakers recognized that the simultaneous leadership turnover in Seoul, Tokyo, and Washington represents a fundamental test regarding their partnership’s institutionalization.

So far, the second Trump administration has continued Trump’s first-term pursuit of enhanced defense cooperation within the Northeast Asian trilateral channel. For example, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio convened a meeting with his Japanese and South Korean counterparts on the sidelines of this February’s Munich Security Conference. In April, the U.S. Department of Defense, Japanese Ministry of Defense, and Republic of Korea Ministry of National Defense pledged to continue trilateral security cooperation and conducted a Defense Trilateral Talks Working Group meeting and a tabletop exercise in Seoul. Media reports indicate that the administration will prioritize resourcing the Indo-Pacific theater. Nonetheless, it remains unclear if this trilateral security cooperation will engage the three countries’ top leaders or will revert to primarily a ministerial-run enterprise among their defense and foreign bureaucracies.

In principle, cabinet-level engagement should suffice to sustain collaboration on important security projects. But how well the three governments can keep their trade and burden-sharing disputes from disrupting their military cooperation is unknown. Whereas the Biden administration sought to make economic and security cooperation reinforce each other through “friendshoring” U.S. global supply chains and other mechanisms, the Trump administration is trying to combine security cooperation with intense economic competition manifested in a preoccupation with tariffs and trade imbalances. If decreased trade leads to slower economic growth, the three governments will have less revenue to finance their defense budgets. Yet, though new U.S. priorities mean it will become harder to realize previous plans to collaborate on some issues—such as developmental assistance, climate change, or global health projects—the parties can profitably elevate collaboration in other areas, such as defense industrial collaboration, energy security, and pooled shipbuilding.

Another challenge to the trilateral partnership is the ongoing political leadership change in Japan and especially South Korea. Leaders of the Democratic Party of Korea (DPK) made challenging Yoon’s efforts at reconciliation with Japan a constant theme of their critique of the ruling People’s Power Party in recent years. If the DPK candidate wins the June 3 election, the new president could, like past progressive administrations, prioritize strengthening relations with Beijing, Moscow, or Pyongyang rather than with Tokyo. Even if the South Koreans elect another conservative, there is no certainty the new president would share Yoon’s unwavering commitment to improve ties with Japan despite the difficulties.

Whether the new leaders in Japan, South Korea, and the United States still perceive international security as globally indivisible represents another unknown. Biden, Kishida, and Yoon all believed that adverse European security developments would negatively impact the Indo-Pacific. But some in the Trump administration want NATO allies to focus more on meeting their European commitments rather than contributing to Asian-Pacific security issues, with the important exception of supporting sanctions and export controls. This security shift could result in fewer European freedom of navigation naval patrols in China’s vicinity or a de-emphasis of the so-called NATO-IP4 structure involving the Indo-Pacific Four partners of Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea.

Recent Chinese policies have so alienated the Japanese and South Korean publics that neither of their governments will likely bandwagon with Beijing against the United States, whatever their concerns about specific U.S. policies. Last month, Seoul and Tokyo resolutely resisted Beijing’s entreaties to jointly respond to Trump’s reciprocal tariffs.

Even so, the trilateral partnership remains an essentially top-down project of the three countries’ national security elites, with fickle public support. The new political leaders in Japan, South Korea, and the United States know they can deemphasize the partnership without incurring substantial domestic political costs. For now, though, Tokyo and Seoul are inwardly focused on their leadership transitions while awaiting more clarity regarding what policies Washington will pursue regarding themselves as well as Beijing, Moscow, and Pyongyang.