Though the highly anticipated first phase of a US-China trade deal was sealed this past month, arguments concerning China’s innovation still reference the nation’s “Made in China 2025” plan (MIC25). What is the connection between the trade war and MIC25? Most view the relationship as cause-and-effect; the common consensus is that China’s grand strategy to become world’s manufacturing powerhouse was the key issue leading up to the US-China trade war.

In July 2018, after the dispute began, Beijing decided to remove all references of ‘MIC25’ from public discussion. One view sees this name-drop as a matter of stroking Trump’s ego by giving the appearance of a big win for Trump, while the Wall Street Journal suggests that it was more “cosmetic than real”. But why, exactly, did Beijing alter its rhetoric?

The pressures of the US-China trade war may be the most obvious culprit, as it has stoked fears of China surpassing the US in economic leadership. US Vice President Mike Pence has scapegoated China for protectionism and economic nationalism, and has criticized MIC25 of achieving its goals through intellectual property theft and forced technology transfer. Though some Chinese social media has remained positive, this blind spot presents a challenge for business leaders, global investors, and policymakers alike.

South China Morning Post reported that Trump’s true intention of the trade war was to contain China’s technological ambitions. One could argue that Beijing, in response to the trade war, was actually quite adaptive in rebranding and recalibrating its innovation strategies using stealthy measures. Data collected from the Ministry of Industrial Information Technology (MIIT) suggested that Trump’s trade war strategies have actually had an adverse effect in containing China’s innovation development.

Coincidentally – or perhaps not – the removal of ‘MIC25’ from state documents occurred around the same time as the start of the US-China trade war. Instead of ‘MIC25’ completely disappearing, however, the act of removing MIC25 rhetoric could very well have been an attempt to shift or conceal China’s manufacturing strategies in the greater context of the trade war.

There are several reasons as to why it is difficult to detect this shift in policy priorities. The obvious one is the absence of MIC25 rhetoric in policy documents. Another is the distraction of a back and forth blitzkrieg of tariffs between both sides. Regardless, many believe that MIC25 is still very much alive.

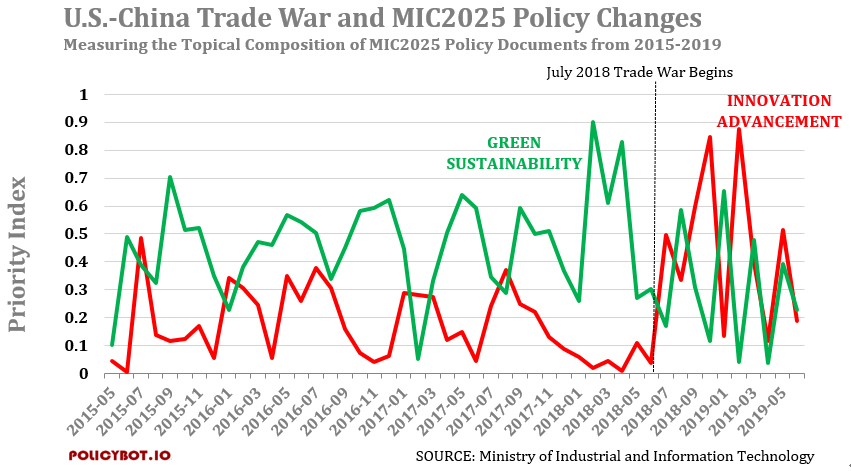

In order to track the residual existence of MIC25, we must understand what its objectives are. The official Made In China 2025 Plan lists four objective themes regarding manufacturing upgrade: 1) innovation advancement, 2) product quality improvement, 3) manufacturing digitization, and 4) green sustainable development. These themes or topics ultimately determine MIC25’s metrics of success. By using data science and machine learning methodologies, we can assess how active, if at all, MIC25 really is within Chinese State economic planning. I developed PolicyBot.io to extract major policy themes from publicly available records to detect change in policy priorities over time.

![]()

By tracking dominant themes in policy documents, I was able to generate a ‘priority index’, which reflects the dominant policy topics at play. 28 new policy documents were detected by my machine learning model, with 90% accuracy on the test set.

The data can help us interpret the situation in a few different ways. By looking into these 28 cases, we can see signs of a shift in the topics discussed during the pre- and post-trade war period. The evidence seems to hint that ‘green sustainability’ policy topics were perhaps the primary focus of Chinese policymakers during the pre-trade war period, but afterwards they tend to give more attention to ‘innovation advancement’ policy topics. We can also conclude that ‘green sustainability’ and ‘innovation advancement’ had a competing, negatively correlated relationship. This could possibly reflect the central planners’ indecisiveness, limited resources, or perhaps the complexity of balancing each priority of MIC25.

From these policies, one can conclude that MIC25 priorities are shifting to innovation-building, but we should dig deeper to see what these innovation initiatives actually look like. A recent paper published in July 2019 from Berlin-based Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) not only confirms my findings but also unveils the construction of a comprehensive network of manufacturing innovation centers across China. There are about 700 key state-laboratories, 25 of which are focused on basic research and 40 of which are national-level “core” innovation centers and “supplementary” innovation centers at the provincial level. The purpose of these national provincial innovation centers is to accelerate the research to commercialization process.

There are several reasons as to why, perhaps, Beijing is recalibrating MIC25 priorities in response the trade war. Shan Guo, an economic policy consultant of Beijing-based technology consulting startup Plenum.ai explains that the change could have been caused by both external and internal factors: "The trade war with the US has revealed how much China depends on foreign technology, and thus created a sense of urgency among the leaders to prioritize the development of China's innovation capacity," she said, "and China's economy is slowing more than expected, making leaders pause on policies that may have a negative impact on the economy, such as those promoting green development.” Anna Holzmann of the Berlin-based MERICS Institute also echoes the prevalence of those same external factors. In addition, she points to internal inefficiencies, like misallocation of resources and redundancy of overlapping responsibilities at the local level, as reasons for Beijing to favor centrally-guided innovation. She proposes the priority shift may not be completely attributed to the trade war. It may be partly also a response to certain internal governance-related inefficiencies.

Trump’s original intention in waging the trade war was to discourage unfair trade and tech-transfer practice as well as contain China’s technological ambition. This has somewhat backfired. Whether or not the trade war had an impact, the MIC25 has adapted quite well behind the narrative of ‘being technologically independent’ from foreign tech suppliers. It can be argued that the trade war has not only influenced Beijing to change China’s technological-economic priorities, but it has also made the US realize they need to create a comprehensive plan. As Beijing continues to stealthily implement MIC25-like initiatives, both domestic and foreign firms will most likely have to continue to comply with China’s industrial policy.

Under the recent temporary halt of tariffs, the ability to understand the dynamics of MIC25’s industrial policy relating to the trade war can be helpful in recoupling the two economies. At the same time, both sides should also equip themselves for the worst to come. The US, in many ways, is still the top producer of AI research in the world, while China is fundamentally better at implementing and deploying AI into the market. As both sides continue to hack out “The Great Deal” across the negotiation table, the US and China should be proactive in brainstorming new methods to recouple in ways that do not display their technological prowess or nationalistic tech ambitions, but rather serve to benefit the greater humanity to fight more pressing problems like climate change and extreme poverty.