Click to read the latest China-US Focus Digest

At the beginning of 2022, I would like to review both the near- and long-term prospects of the Chinese economy. I will begin by looking at the underlying trends in the Chinese economy. Then I will examine near-term performance, followed by some long-term forecasts. Brief concluding remarks are made at the end.

Underlying trends

What are some of the major underlying trends in the Chinese economy over the next decade? We can identify the following major directions.

The dual-circulation economic development strategy.

As President XI Jinping announced some time ago, China will pursue a dual-circulation development strategy. There is a domestic circulation and an international circulation, but domestic circulation plays the primary role, which is to be expected for large continental economies like China (and also the United States). However, the dual circulations complement one another. The Chinese economy today cannot operate without imports, nor can the rest of the world operate without Chinese exports. The adoption of a dual-circulation strategy by China is evidence of its recognition that total self-sufficiency is not a viable alternative and of its continuing commitment to an open economy and to economic globalization.

The Chinese ratio of international circulation to domestic circulation was below 10 percent before 1981, when it began to rise. It reached a peak of almost 70 percent in 2006 but declined to 35 percent by 2020. The U.S. ratio was around 20 percent between 1980 and 2000 and rose to a peak of 30 percent in 2011, but declined to 23 percent in 2020. It is expected that the ratios for both countries will be declining more over time and will eventually reach similar levels.

Peaking of carbon emissions by 2030 and the achievement of carbon neutrality by 2060.

President Xi also committed China to top out its carbon emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. These are challenging but feasible objectives. It is envisioned that they will be met through the growth of electric vehicles; a network of high-speed trains substituting for airplanes in domestic travel; the massive expansion of renewable energy, including hydropower, massive solar and wind power farms (for example, in the Gobi Desert); the introduction of nuclear fusion as sources of electricity generation, replacing traditional fossil fuels; the use of ultra high-voltage transmission lines to deliver electricity inexpensively to wherever it is needed; and large-scale reforestation. China will become as green as it can be.

Common prosperity

The common prosperity promoted by President Xi should not be equated with simple redistribution. It genuinely means giving other people who have not gotten rich yet an opportunity to become so.

The recent establishment of the Beijing Stock Exchange is a concrete indication that the private sector, consisting mostly of small and medium-sized enterprises, will be allowed to continue to grow and prosper. These private enterprises can use equity financing to substitute for debt financing, resulting in a reduction of the overall level of leverage in the economy and thus ensuring greater macroeconomic and financial stability. Eventually, China can probably use even more stock exchanges in different parts of the country — for example in Chongqing and Tianjin — so that more private entrepreneurs can have access to equity financing and the opportunity to grow and prosper.

China-U.S. competition the norm

The strategic competition between China and the United States is likely to be the norm for the next decade or so. National security is often just a convenient excuse for the U.S. to impose unilateral sanctions on China, while China actually poses no real threat, military or otherwise, to the existence and continued prosperity of the U.S. However, it can potentially cause a problem for the maintenance of global hegemony by the U.S. because, as Professor Noam Chomsky of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology once pointed out, China is one of very few countries that can actually say no to the U.S. As the global hegemon, the U.S. cannot allow any country to say no and get away with it, because this may encourage other countries also to say no, and fairly soon its global hegemony is no more.

The (bipartisan) military-industrial complex in the U.S., which was first identified by U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower in 1961, is intent on continuing to be the global hegemon and will use any and all means necessary to prevent China’s peaceful rise. It will end either when China’s rise is halted, or when the U.S. is finally convinced that the effort is futile and won’t incur unacceptably high costs to the U.S. itself. That is why China-U.S. competition is likely to be the norm for the next decade or so and why the trade war is unlikely to end anytime soon. Things will eventually get better, but it will take a while.

However, the competition is not likely to result in a hot war between China and the U.S. because the resulting casualties and losses would be enormous on both sides. There would be no winners, only losers. If the former Soviet Union and the U.S. were able to avoid war in the last century, it is highly unlikely that China and the U.S. will go to war in this century. However, to maintain peace, China must have and maintain an effective deterrent against a first strike.

Decoupling of the two economies to a certain extent is also inevitable, but there has been some experience with partial de-coupling in the past. After the 2008 global financial crisis, China and East Asia continued to grow while the U.S. and the West stagnated. Thus it is possible for the Chinese and East Asian economies to grow without the West. Moreover, while the artificial decoupling of the global supply chains will cause some transitional problems for the Chinese economy, once a second source for a product is developed, export controls by the U.S. and other countries are no longer useful and will likely be discontinued.

Use of the U.S. dollar for worldwide invoicing, clearing and settlement will also decline gradually, with the greater use of own currencies for such purposes — as, for example, between China and Russia, and between China and Indonesia. The purpose of capital control is the regulation of volatile short-term capital inflows and outflows, not long-term flows. Every country welcomes long-term capital inflows, but short-term capital inflows and outflows do not bring any benefit to either the originating or the recipient countries.

The use of digital currency, with its distributed ledger feature at both the retail and wholesale levels, can greatly simplify capital control by distinguishing between short-term and long-term capital flows. Similarly, the trading of China depositary receipts (CDRs) of foreign companies on Chinese stock exchanges, including those from the U.S., can allow a transitional period for the full lifting of capital controls. China will have the largest pool of savings in the world, and raising capital in China is beneficial to foreign companies.

Near-term performance

The rate of growth of Chinese real GDP in the first-three quarters of 2021 was 9.8 percent, even though the quarterly year-on-year rate of growth declined from 18.3 percent in Q1 to 7.9 percent in Q2 and then to 4.9 percent in Q3 (mostly due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic). Even if there is zero growth in Q4, the annual rate of growth would still be a very respectable 7.35 percent.

To achieve an annual rate of growth of 8 percent for 2021, the Q4 year-on-year rate of growth need be only 2.6 percent, which should be doable. For 2022, the general expectation is that the non-mandatory target may be set between 5 and 6 percent.

The rate of growth of U.S. real GDP in the first-three quarters of 2021 was 5.0 percent, even though the quarterly year-on-year rate of growth declined from 6.3 percent in Q1 and 6.7 percent in Q2 to 2.1 percent in Q3. Even if there is zero growth in Q4, the annual rate of growth would be a very respectable 3.8 percent. To achieve an annual rate of growth of 4.5 percent, the Q4 year-on-year rate of growth need be only 3.0 percent, which should also prove feasible. For 2022 and beyond, the general expectation is that the U.S. economy will be able to grow at an average annual rate above 3 percent.

There are, of course, some lingering questions, which will be considered below one by one.

First, will the COVID-19 pandemic retard Chinese economic growth? There may be some negative effects, but not hugely significant ones. The maximum damage is no more than 1 percentage point.

Second, can tariffs on Chinese exports hurt the Chinese economy? The evidence from the past few years, during which Chinese exports faced heavy U.S. tariffs, suggests that the negative impact would be small, and in any case the Chinese economy is no longer export-oriented. It maintains an approximate balance in international trade and is mostly driven by internal demand — household consumption, public goods consumption and gross fixed investment.

Third, can export controls on American high-technology products slow the Chinese economy down? Yes, they can, at least to a certain extent. But for really essential national projects, such as the construction of supercomputers, cost per se is not a major consideration. Chinese supercomputers today are built entirely with domestically produced components, including semiconductors.

Fourth, will a financial crisis be triggered by the debt of overextended real estate developers, or those of local government financing vehicles (LGFVs)? The currently available evidence suggests that this problem is entirely manageable. Official central government and provincial government debt combined is less than 50 percent of Chinese GDP. By comparison, U.S. federal government debt alone exceeds 100 percent of GDP. In Japan it’s more than 250 percent. The Chinese central government has not provided any loan guarantees for real estate developers or LGFVs and is most unlikely to come to their rescue if any of them fails. A default or two of these debtors can in fact help to rein in shadow banking, which is difficult to regulate.

Fifth, the construction sector, including building materials, is a major part of the Chinese economy and is dependent on demand generated by investment in infrastructure and real estate. It may be impacted by the massive failure or insolvency of real estate developers; however, residential investments can be supported not only by owner-occupied housing but also by rental housing. The central government can promote rental housing as a viable alternative to owner-occupied housing, thus maintaining demand in the construction sector. The ultimate total residential housing demand is of course the same, but there can be a different equilibrium between renting and owning.

Long-term forecasts

Our long-term forecasts suggest that Chinese real GDP will surpass U.S. real GDP in 2030, with $29.67 trillion compared with $29.26 trillion in the U.S. (in 2020 prices). They also suggest that Chinese real GDP per capita will remain significantly below the U.S. real GDP per capita in 2030, with $27,100 compared to $96,500 in the U.S. (in 2020 prices), or less than 30 percent.

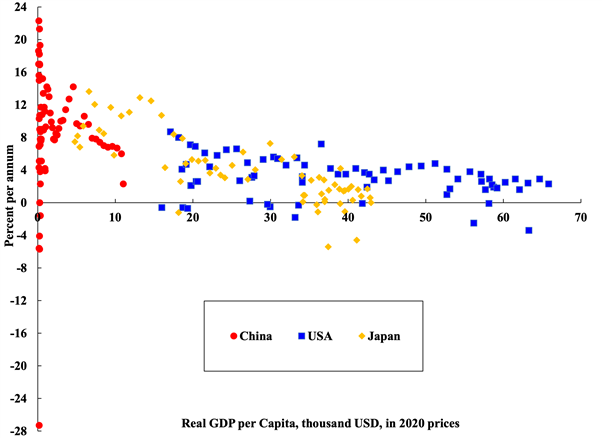

It is true that the Chinese economy cannot continue to grow at close to 10 percent per year indefinitely, as it did between 1978 and 2018. In fact, it is an empirical regularity that as the real GDP per capita of an economy grows, the real rate of growth of the economy declines. This is demonstrated in accompanying chart in which the real rates of economic growth of China, Japan and the U.S. are plotted against their respective real GDPs per capita. As expected, there is a negative relationship between the real rate of growth and real GDP per capita.

Chart: Growth of real GDP vs. real GDP per capita

China, Japan and the U.S.

However, we note that the Chinese economy currently operates in a range of real GDP per capita that permitted high rates of growth for both Japan and the U.S. By 2030, the Chinese economy will be able to grow at more than 6 percent annually. Perhaps when Chinese real GDP per capita reaches $35,000 (in 2020 prices), the Chinese real rate of economic growth will decline to below 5 percent.

Conclusion

The long-term prospects for the Chinese economy are very good indeed, even though its average real rate of growth is likely to be around 6 percent rather than 10 percent. Moreover, it will be mainly driven by domestic demand, rather than exports. Technical progress, or growth in total factor productivity, will also become an important source of Chinese economic growth. However, it is essential for China to maintain economic openness. Self-reliance should never be equated with total self-sufficiency. Without economic globalization and China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, the Chinese economy would not be where it is today. We should always remember there must be dual circulation.

That said, China-U.S. strategic competition is likely to be the norm, possibly for the rest of this decade. I remain optimistic that rationality will prevail and there will not be a hot war, just as the former Soviet Union and the U.S. did not go to war in the last century.