Despite all the predictions of doom by Western pundits in 1997, Hong Kong has done well since its reversion of sovereignty to China twenty years ago. The “handover” was an historic event, hailed by Chinese everywhere, regardless of political persuasion, as the final closure of the century-long humiliation suffered by China at the hands of the Western powers beginning with the Opium War. Even Taiwan sent a delegation to Hong Kong for the handover ceremony.

The transition itself went smoothly under the leadership of TUNG Chee-Hwa, the first Chief Executive (CE) of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). However, almost immediately after the handover, East Asia, including Hong Kong, was engulfed by the East Asian currency crisis, leading to widespread massive devaluation (except in Hong Kong and the Mainland) and economic recession everywhere (and the bursting of the housing price bubble in Hong Kong). This was followed by the outbreak of the “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)” in Hong Kong in 2003, the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and the subsequent European Sovereign Debt Crisis, which all impacted the economy negatively.

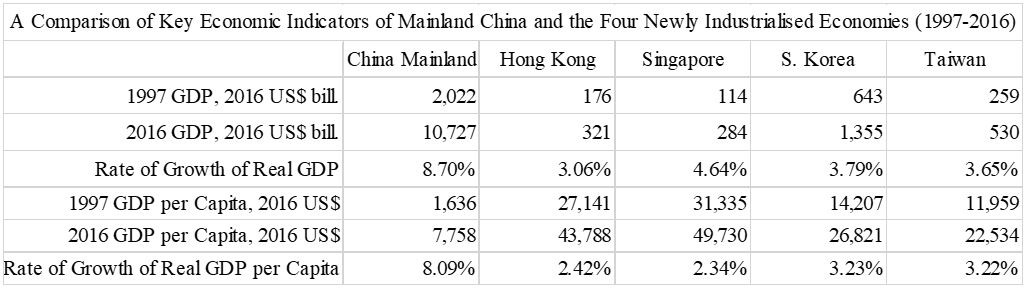

However, Hong Kong, ever so resilient and resourceful, survived all these crises. Today, Hong Kong still remains substantially ahead of South Korea and Taiwan in real GDP per capita but behind Singapore by 15% (see the table below). The most significant change is the decline in the size of the Hong Kong GDP relative to the Mainland—it went from 8.7% (176/2022) to just below 3% (321/10727) and on a per capita basis from 16.6 (27141/1636) times to only 5.6 (43788/7758) times.

However, during the past two decades, income inequality in Hong Kong has risen sharply, as has the cost of housing, which doubled between 1997 and 2016. A significant proportion of Hong Kong citizens live in tiny, sub-standard, illegally subdivided rooms, which are a major potential fire hazard. We just pray that something similar to the Grenfell Tower fire in London would not happen here. The outgoing CE, Chun-Ying LEUNG, has tried his best to improve the housing situation. We believe the incoming CE, Carrie LAM, will continue working on it. However, this problem cannot be solved overnight, or even in a couple of years. We need a vision and a credible plan, so that people know that decent and affordable housing will be available for all in, say, ten years. This should help dissipate a great deal of the latent anger among our citizens.

Politically, Hong Kong has not fared so well. It was a shame that the universal suffrage plan failed to pass. However, the “One Country, Two Systems” principle has been widely misunderstood. It is meant to be a single country, but with one part, the Mainland, operating under the socialist economic system and the other part, Hong Kong and Macau, operating under the capitalist economic system. It is not meant to be two different political systems. Whatever happens to the “two systems” in 2047, it will always be “one country”. It is therefore essential to embrace the idea of “one country”, even if one does not support the current policies of the Central or the HKSAR Government. To this end, the teaching of China’s own history and culture, which span 5,000 years, in our primary and secondary schools is important to the nurturing of the sense of one nationhood. Chinese History, which was a mandatory subject in primary and secondary schools before the “handover”, should have continued to be mandatory.

At the present time, both the Mainland and Hong Kong economies are undergoing important transitions—with the Mainland trying to achieve a “New Normal”, with reduced reliance on exports and fixed investment and greater focus on domestic demand and innovation, and Hong Kong needing to find another role for itself. Before 1949, Hong Kong was an entrepot port, serving southern China. The establishment of the People’s Republic of China halted the entrepot trade and forced Hong Kong to develop its light manufacturing industries in the mid-1950s, with the support of the government, which provided land for factories in Kwun Tong. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the rising wage rate in Hong Kong and the competition from Taiwan and South Korea caused light manufacturing to decline. But the Chinese economic reform and opening to the world in 1978 allowed Hong Kong manufacturers to re-establish their operations on the Mainland, taking advantage of the lower costs of labour and land. Hong Kong also became once again the entrepot port and the source of the then much needed foreign direct investment (FDI) and foreign exchange for the Mainland. The Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEx) began to list the shares of the Mainland enterprises in the early 1990s, also helping to provide equity capital and foreign exchange. It is no exaggeration to say that Hong Kong was indispensable for the initial success of the Mainland economic reform and opening.

However, as the Mainland economy continues to develop and grow, Hong Kong’s role gradually diminishes: The growth of Mainland trade has slowed as the Mainland reorients its economy to its own huge domestic market; in any case, most of the trade is now carried out directly through Mainland ports. The Mainland has become a net capital exporter rather than importer. Thus, the Hong Kong economy has become more dependent on the Mainland rather than the other way around.

Hong Kong is likely to lose the advantage of the full convertibility of its currency over the Mainland in the next five years; it will also lose much of its advantage of a free trade port on account of the Mainland’s accession to the WTO and continuing liberalization. The “Belt and Road (B&R)” and the “Greater Bay Area (GBA)” initiatives can give the Hong Kong economy yet another new lease on life. They will open up significant new and continuing economic opportunities for Hong Kong to re-invent itself once again. B&R is a multi-country, multi-decade development plan with the objective of linking and transforming the economies of Asia, Europe, Africa and Oceania, and creating sustainable trade and investment exchanges where none exist before. Hong Kong is ideal as a centre for the financing of the “B&R” infrastructure projects because of not only its complete capital mobility, full currency convertibility, stable exchange rate, rule of law, and low income tax rates (no tax on interest, dividends and capital gains), but also its ready access to the huge Mainland capital market and savings pool, and the support of the Central Government, the principal sponsor of B&R. Hong Kong can readily put together a financing package that includes both public and private participation, equity and debt, and short- and long-term bonds and notes, and possibly in multiple currencies. However, it must develop a more active bond market with sufficient liquidity.

Hong Kong is also an ideal home for a B&R region-wide stock market, especially for enterprises in the developing economies. In 2015, the average daily turnover of Mainland stock exchanges combined was more than US$41 trillion, compared to US$30 trillion for the New York Stock Exchange and US$2 trillion for the HKEx. This demonstrates the huge buying power of Mainland investors and what it can do to attract major enterprises elsewhere to list their shares on HKEx. Hong Kong can also serve as a springboard for outbound Mainland direct and portfolio investment because of its international links and highly developed professional services sector. B&R will further increase demands for casualty, property and life insurance, which have already been growing by leaps and bounds, as do the derivative demands for re-insurance. In addition, since the Mainland is potentially a major sources of risk capital, an international re-insurance center can be developed right here.

GBA, which comprises eleven cities of the Pearl River Delta, including Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Macau, will provide Hong Kong with its economic hinterland. Taking advantage of the presence of light and heavy manufacturers, high-technology enterprises, inventors, entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, start-ups, investors and research universities in the GBA, Hong Kong can potentially become a truly full-service international financial centre that combines the Silicon Valley, New York and Zurich into one. It can become the region’s venture capital and private equity hub, the market of choice for the flotation of stocks and bonds, including “Initial Public Offerings (IPOs)”, and a centre for investment banking, including “Mergers and Acquisitions (M&As)”, and re-insurance. However, it is necessary to promote the free flow of goods and services, people, capital and information as well as the sharing of basic infrastructural facilities within the GBA. One possible approach is to establish a pilot GBA Free Trade Area. The GBA has the potential of overtaking the U.K. to become the world’s fifth largest economy in ten years’ time.

Positive non-interventionism, which provided a convenient excuse for the government not to do anything, no longer serves Hong Kong’s interests. Long-term planning and coordination are needed to realize the full potentials of both B&R and GBA. Hong Kong must make itself once again indispensable and irreplaceable, doing what other Chinese cities cannot do, but at the same time sharing the prosperity with them. Hong Kong alone cannot make it.

(A shortened version of this paper appeared in South China Morning Post, Hong Kong, 1 July 2017.)