The Arctic represents a small but growing part of China's long-term quest to secure access to natural and energy resources and to gain and subsequently maintain greater control over the world's transportation highways. For China the Arctic represents a region of stability, devoid of conflict, and lacking the influence of a clear hegemon, i.e. the United States, in which it can expand its economic reach. To this end China is supportive of the region’s existing security architecture, which allows it to integrate the Arctic into its own development agendas, e.g. the Belt and Road Initiative, largely unopposed.

China's interest in the Arctic is two-fold: access to the region's vast natural resources, including Russian gas and oil and the use of Arctic shipping routes, namely the Northern Sea Route (NSR) and Northwest Passage (NWP), to import said resources as well as export its own goods. Thus, the region’s resources and shipping lanes offer an opportunity for geographic diversification of its energy imports specifically and its international trade more generally.

China’s economic and geopolitical security depend on unimpeded access to a number of waterways, primarily along the Suez Canal Route, over which the country exerts little control. It has been a long-stated goal of the Chinese leadership to adopt measures to overcome this strategic vulnerability known as the “Malacca dilemma” and counteract the United States’ control of vital shipping lanes. In this respect, China's efforts to expand its naval capacity, investments in ports along its main trade routes, and construction of airfields and related infrastructure on shallow reefs in the South China Sea are part of the country’s attempt to gain greater control over its key waterways.

Similarly, access to the Arctic's resources and shipping lanes will allow for variegation of supply and in the not-too-distant future an alternative connection to China's most important market – the European Union – along routes outside the direct influence or control of the United States. As part of its newly released Arctic policy China aims for commercial and regularized operation of Arctic shipping routes with the goal to integrate a “Polar Silk Road” into its Belt and Road Initiative. Chinese investments into Arctic infrastructure such as the Belkomur railway line and the Arkhangelsk deep-water port foreshadow the growing importance of these trade routes.

For China the Arctic represents a largely blank geoeconomic canvas outside of the United States’ sphere of influence in which it can lay the foundation today for significant economic and geopolitical rewards in the future. As such, China will continue to work within the existing structure of Arctic governance and utilize the region’s exceptionalism – an apolitical space removed from traditional power dynamics – as a buffer against the United States’ influence.

The European Union and United States’ sanctions targeting Russian Arctic hydrocarbon development further accelerated China’s engagement in the region. The country’s financing and technical support was crucial to the development of Russia’s Yamal LNG project, which upon completion was hailed as the first large-scale overseas project of the Belt and Road Initiative. Strategic cooperation agreements between the China Development Bank and the China National Petroleum Company, both already engaged in Yamal LNG, for the larger Arctic LNG 2 project were signed in late 2017. While the extent to which Russia will welcome additional Chinese investments – and influence – remains to be seen, the two countries understand the region’s political stability and the absence of conflict as beneficial for the rapid development of its economic potential.

China’s advance into the Arctic is abetted by the power vacuum created by the United States’ absence from the region. The United States sees little economic benefits from a greater involvement in the Arctic’s future. The United States’ single ageing polar-class icebreaker is a symbol of its inability to commit the required investments to expand its role in the region. Paired with a shortage of political will and a lack of understanding of the importance of the region has left it, at least thus far, unable to counteract growing Chinese influence. As it stands China faces little sustained opposition by any of the Arctic states to incorporate aspects of the Arctic into its economy and make use of the region for strategic gains.

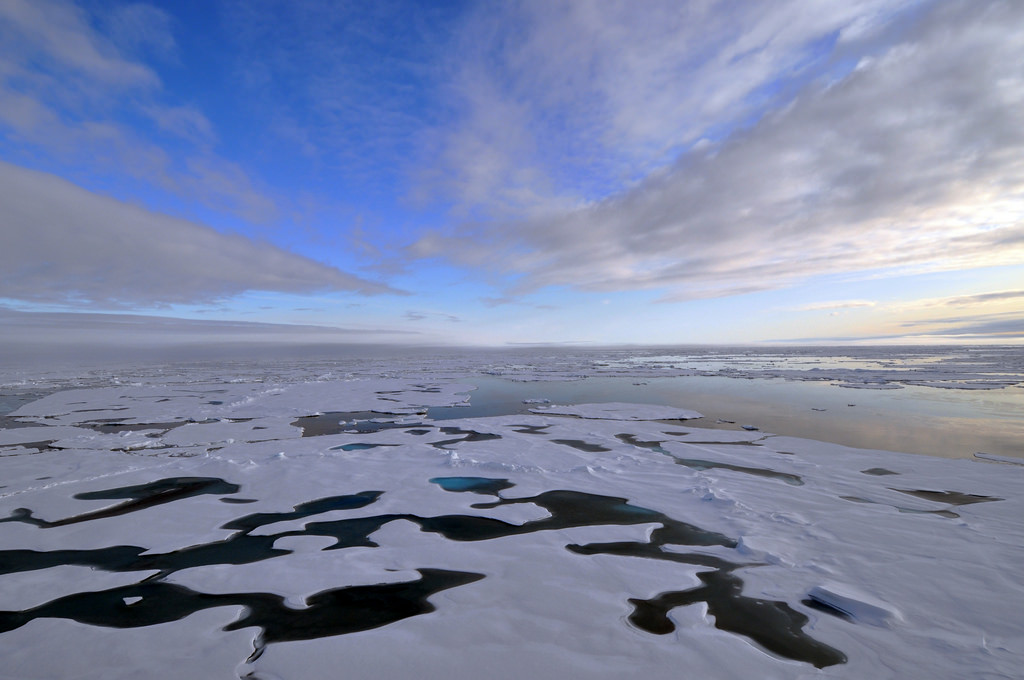

Due to the Arctic’s unique environment, all economic activity, be it the exploitation of natural resources or increased shipping activity, comes with significant risk. Despite a reduction of ice coverage during the summer months navigation in ice-infested waters leaves little margin for error. A number of near-misses along the NSR, including collisions between two Russian oil tankers in 2010, indicate that the question of a major accident is not a matter of if but when.

While shipping traffic in the immediate future will be concentrated along the Russian coastline, primarily to export hydrocarbon resources, a full-fledged future “Polar Silk Road” will undoubtedly make sustained use of the waters of the central Arctic Ocean and the NWP. Seasonal variability of ice conditions along these new routes, lack of accurate navigational charts and aids, and increased distance to search and rescue facilities will further enhance the risk of such operations.

The point here is that it is not China’s economic ambitions for the Arctic per se which enhance environmental impacts, but economic activity in general. As with other highly frequented waterways – the Strait of Malacca sees more accidents than any other shipping channel – the setting of rules and their enforcement will be essential. In this regard the recently-adopted Polar Code can be but a first step to mitigating some of the risks associated with operating in the Arctic.

While the integration of the Arctic region into the global economy appears inevitable and great powers, like China, will undoubtedly seek to benefit from its material riches and strategic value, it will be the Arctic states’ continued responsibility to exercise and enforce responsible stewardship over the region.