In his New Year's Day tweet, US President Donald Trump lambasted Pakistan for failing to cooperate sufficiently with his country in the fight against terror, blaming the latter for "thinking of our leaders as fools" and having "given us nothing but lies and deceit". On January 4, the White House announced it would suspend most security assistance to Pakistan before it promises to crack down on all terrorists in the region. While bringing new variables to the anti-terror endeavors in South Asia, this move has revealed the Trump Administration's narrow-minded interpretation of the international campaign against terror.

US-Pakistan tensions over the fight against terror started much earlier. Immediately after the 9/11 attacks, then State Secretary Colin Powell told Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf in a phone call to "either be with us, or be our enemy". Under pressure, the latter agreed to support the US anti-terror actions in Afghanistan. Yet then Pakistani director of the Inter Services Intelligence Directorate told the then US ambassador to Pakistan Wendy Chamberlin that “Real victory will come in negotiations…If the Taliban are eliminated...Afghanistan will revert to warlordism.”Obviously Pakistan had to a great extent been forced to join the US-led anti-terror camp, and their differences have never disappeared.

As the campaign deepens, these tensions have also begun to become more prominent. After Osama bin Laden was killed in 2011, there was much debate in the US over whether Pakistan is a "friend" or "enemy". Actually Pakistan paid an extremely heavy price for supporting the US' anti-terror campaign in Afghanistan. According to Pakistani statistics, the country spent as much as $100 billion on fighting terrorism from 2003 to 2017, far more than all the US assistance combined. A large number of Pakistani troops, police officers, and law-enforcement officers have died in the process, along with numerous civilians who lost their lives in the collateral damage of US drone strikes. And these are just the very limited "visible costs" in the campaign. The greater cost has been incurred by Pakistan openly fighting against the cross-border jihadi terrorist organizations, the subsequent retaliatory attacks as well as the worsening of domestic factional discord, outstanding security concerns, and deteriorating investment environment. Statistics from the South Asia Terrorism Portal shows 29,033 Pakistanis died in terrorist attacks in Pakistan between 2001 and 2017, including 6,887 security personnel, a figure much bigger than the 2,297 American soldiers who died in Afghanistan during the same period. In 2000, the figure for Pakistan fatalities was only 45; while in 2012, it grew to 3,759, including over 700 security personnel.

US-Pakistan differences lie not in the fight against terror per se, but in their ideas about the future of Afghanistan. According to the Pakistanis, the US has already defeated the bin Laden-led Al-Qaeda, but is unable to root out the Taliban, the future of Afghanistan rests on political reconciliation, and the Taliban will be an indispensable part in that process. To the Americans, however, although the Al-Qaeda influence in Afghanistan is fading, the US is not able to preserve the achievements of the war against terror in the country, i.e. unable to establish an Afghan government that is stable, sustainable and pro-US. Obviously the Taliban is the root cause of the problem. No US administration can allow the Taliban to have any role in Afghanistan’s future political process, because that means surrendering the fruits of US anti-terror effort in Afghanistan since 9/11.Such a policy is the root of the US' present policy dilemma: on one hand, since the Obama administration, the US has wanted to scale down its anti-terror campaign and focus on domestic economic concerns; on the other hand, there is no way to resolve the current political impasse in Afghanistan. A hasty withdrawal might allow the situation in Afghanistan to spiral out of control, making it once again a safe haven for global jihadists, or triggering a regional crisis like the rise of ISIS in Iraq.

With ISIS crushed in Iraq and Syria, ending the war on terror in Afghanistan has become a priority for the Trump Administration. For the time being, no solution regarding the peace process in Afghanistan can ignore the role of the Taliban. Pakistan may play an important role in the process, but its role should not be exaggerated. First, the Afghan Taliban has become severely divided following the death of Mullāh Umar Muhammad, and Pakistan has limited influence on the diehard elements, or those Western media deems the "bad Taliban" who refuse peace negotiations; second, unlike Al-Qaeda, the Taliban is a radical armed faction that is rooted deeply in local Afghan communities, and woven broadly in a cross-border network, so that neither the US nor Pakistan can easily defeat it; last, the Trump Administration's public accusation and economic restrictions will make Pakistan worry even more about the cost of retaliation in the fight against terror. In other words, losing confidence in the US may make Pakistan even less likely to risk suffering terrorist.

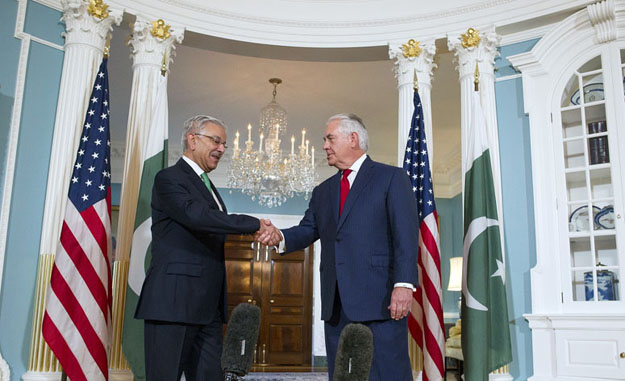

Perhaps the Trump Administration can easily turn Pakistan into a scapegoat for the US' own failure in Afghanistan, but that is no solution to its Afghan dilemma. Perhaps Pakistan is not an ally of the US, but nor should it become an enemy. It is an important partner in the global campaign against terror. Cooperation needs to be based on common goals and interests, as well as mutual respect and understanding, rather than rude accusation and coercive pressure.