The U.S. operation to capture Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro demonstrates Washington’s military power and intent to counter rival influence, particularly China, in the Western Hemisphere, but it violates international law and risks destabilizing the region. Such interventions often produce unintended consequences, embolden other powers to challenge norms, and expose smaller states to coercion, highlighting the dangers of unilateral actions under the guise of national or hemispheric security.

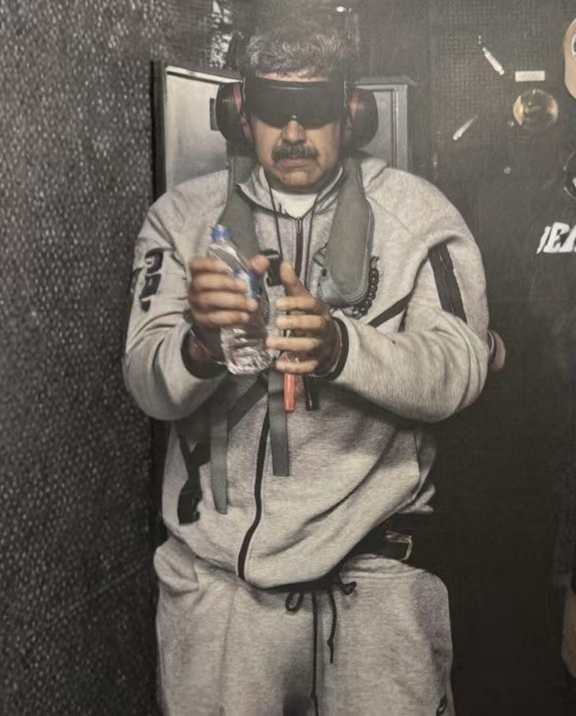

U.S. President Donald Trump, CIA Director John Ratcliffe and Secretary of State Marco Rubi monitors U.S. military operations in Venezuela from Mar-a-Lago Club in Palm Beach, Florida, on Saturday, January 3, 2026. (Official White House Photo by Molly Riley)

The shock and awe of the United States’ operation to capture Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro displayed America’s enduring military might. It also showed Washington’s resolve to enforce the Trump Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, presaging U.S. efforts to roll back the growing economic and diplomatic influence of rivals, notably China, in the Western Hemisphere. However, such actions also undermine a rules-based order and send dangerous signals to rivals and allies alike.

Regardless of one’s view about Maduro’s governance or politics, the brazen attack on a sovereign territory and the abduction of its sitting leader for trial in another country violates international law and undercuts a rules-based order. That such intervention by Washington, especially in Latin America, is not unprecedented does not make it right. In fact, it only adds to the litany of historical wrongs. Maduro was not the first head of state captured by the U.S.. The first Philippine president, Emilio Aguinaldo, was taken by American occupation forces in 1901. Panamanian general and de facto leader Manuel Noriega, who previously enjoyed U.S. support, was taken in 1990 after a US military invasion of the Central American country, the biggest operation since the Vietnam War. Saddam Hussein was caught in 2003 after a U.S.-led assault on Iraq as part of the broader war on terror. For sure, the U.S. has legitimate security interests to protect and has the right and resources to contribute to shaping a stable and thriving neighborhood. The question is whether direct intervention was the appropriate tool.

Interventions in the affairs of other countries, no matter the pretext or intentions, do not necessarily lead to desired outcomes. And all too often they lead to far worse consequences. The downfall of Saddam Hussein created a power vacuum that bred sectarian conflict between Shia and Sunni armed groups and gave rise to the militant Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Syria was engulfed in 13 years of civil war from the so-called Arab Spring until the fall of the Assad regime in December 2024. Libya was likewise plunged into turmoil and has had no stable, cohesive government since the ouster of its longtime leader Muammar Qaddafi in 2011. Getting into a war is easy. The result and the exit are often messy.

In the case of Venezuela, it is unclear if interim President Delcy Rodriguez will carry out U.S. directives. How Venezuelans view her leadership, if she does, is also a consideration. Days after Maduro’s capture, the regime’s unofficial enforcers – armed paramilitaries known as colectivos – set up checkpoints and conducted searches to root out alleged traitors that enabled the U.S. operation. These loyalists, the Venezuelan military and Colombian left-wing rebel groups operating near the border – not the political opposition or democratic civil society groups – seem to be the resilient actors likely to survive and even gain from Maduro’s capture. Whether the U.S. will ratchet up pressure on Rodriguez or follow up with boots on the ground to achieve its goals remains to be seen. Doing so can be a slippery slope and may go against President Donald Trump’s wish to extricate the U.S. from forever wars. The prospect of instability may also dissuade U.S. oil majors from returning to Venezuela, one of Trump’s aims in the South American country.

Washington’s pretext for abducting Maduro is also disturbing. The idea that non-traditional security threats like drug trafficking and illegal immigration justify the use of force against neighbors is dangerous. Instability in Myanmar reared industrial-scale illegal gambling and scam operations targeting the Chinese public, among others. Does it give China a license to attack Myanmar, more so run it as Naypyidaw struggles to control the situation on the ground, especially in border areas where many transnational criminal activities occur? That the U.S. can use force to re-access Venezuelan oil and compel Caracas to pay debt owed to U.S. companies is likewise a risky proposition. This will put alleged Chinese debt-trap diplomacy to shame. Beijing financed and built various infrastructure projects abroad under its massive Belt and Road Initiative. Its companies have mining and petroleum assets worldwide. Is China now justified to employ force if host countries nationalize their investments or refuse to service their debts? Moreover, America’s brazen regime change in Venezuela outclassed China’s supposed clandestine but slow-boil influence operations and united front work activities abroad.

The first photo of deposed Venezuelan dictator Nicolas Maduro was released by President Donald Trump.

Exceptionalism and spheres of influence breed contempt from neighbors and competitors alike. Amassing a large naval armada in the Caribbean Sea, effecting regime change in Venezuela, and designs over Greenland give shape to Trump’s vigorous revival of the 19th-century Monroe Doctrine. Renewing it now, amid escalating great-power competition, may invite reciprocal attempts by rivals. Interference in the domestic affairs of its neighbors and attempts to grab resources (e.g., Venezuelan oil) and territory (e.g., Greenland) may vindicate Russia’s assault against Ukraine and justify efforts to reassert influence in former Soviet Union states. This may also embolden Beijing to alter the status quo across the Taiwan Strait and treat its eastern and southern periphery as Washington treats its backyard. If the U.S. can seize the territory (Greenland) of a fellow NATO ally (Denmark), arguing national security and the need to deter rivals China and Russia, will other allies be spared from similar demands in the future? The U.S. already has an operational base on the world’s largest island, and Copenhagen seems open to negotiations on a larger U.S. military footprint. Hence, attempts to annex the Arctic island only fuel speculation about the real motives. Is unilateral national security or appeals to hemispheric security floated as cover to acquire petroleum and critical minerals or control the northern trade route?

Erosion of international law exposes smaller and vulnerable states living alongside larger and more powerful neighbors. The rise of China gave Latin American countries more options – a huge market for their export commodities and new sources of capital and technology. Undeniably, burgeoning economic interaction can eventually translate to diplomatic and political clout. China is the world’s largest trading and energy and mineral-consuming country, and Latin America has these in abundance. China may desire strategic access and dual-use infrastructure in return for economic largesse, a calculation that may appeal to many emerging and developing countries in the region.

As the region’s hegemon, the U.S. has reason to be concerned about developments that may diminish its longstanding primacy or security interests in its backyard. But should the U.S. have a veto over projects entered into by its sovereign neighbors with other partners? Is Washington willing to offer better terms to offset losses or opportunity costs should its southern neighbors be pressured to drop Chinese offers? In an increasingly complex and uncertain global economy and security environment, many countries are diversifying their trade and security partners. Latin American countries are no different. How and who determines if a certain project is strategic and how will Washington reply to such undertakings? The China-funded Chancay deepwater port in Peru’s Pacific coast, which opened in 2024, is a game-changer in advancing China-South America trade. Will the U.S. restrict its operations to frustrate expanding economic ties between Beijing and its South American neighbors?

Great powers rise and fall, and how they behave may provide a template to successors or challengers. Lessons that the U.S. imparts – intentionally or inadvertently – to China through the attack in Venezuela, as well as expansionist claims over Greenland, will have profound implications.