Acquiring nuclear weapons would not only undermine the global nuclear non-proliferation framework but also deal a fundamental blow to the postwar international order—a prospect that must be met with deep concern and strong opposition from its allies and neighbors.

When Japan’s new prime minister, Sanae Takaichi, falsely claimed recently that “an incident in Taiwan is an incident for Japan,” China lodged strong protests. A senior adviser to the prime minister’s office put forward the idea that Japan could possess nuclear weapons, drawing widespread attention and condemnation from the international community.

In recent years, discussions about Japan acquiring nuclear weapons have been no secret. Certain restless right-wing groups in Japan have persistently advocated revisiting the “Three Non-Nuclear Principles” in an attempt to break through the political and legal barriers preventing the development of such weapons.

Typically, assessments of the risks of nuclear proliferation within the international strategic community encompass two dimensions: intent and capability, and right-wing factions intend to pursue nuclear arms. This has never been a mystery. However, constrained by Japan’s pacifist constitution and facing strong domestic opposition, they face a high bar in translating this ugly intention into political will. Decision-making remains a challenge.

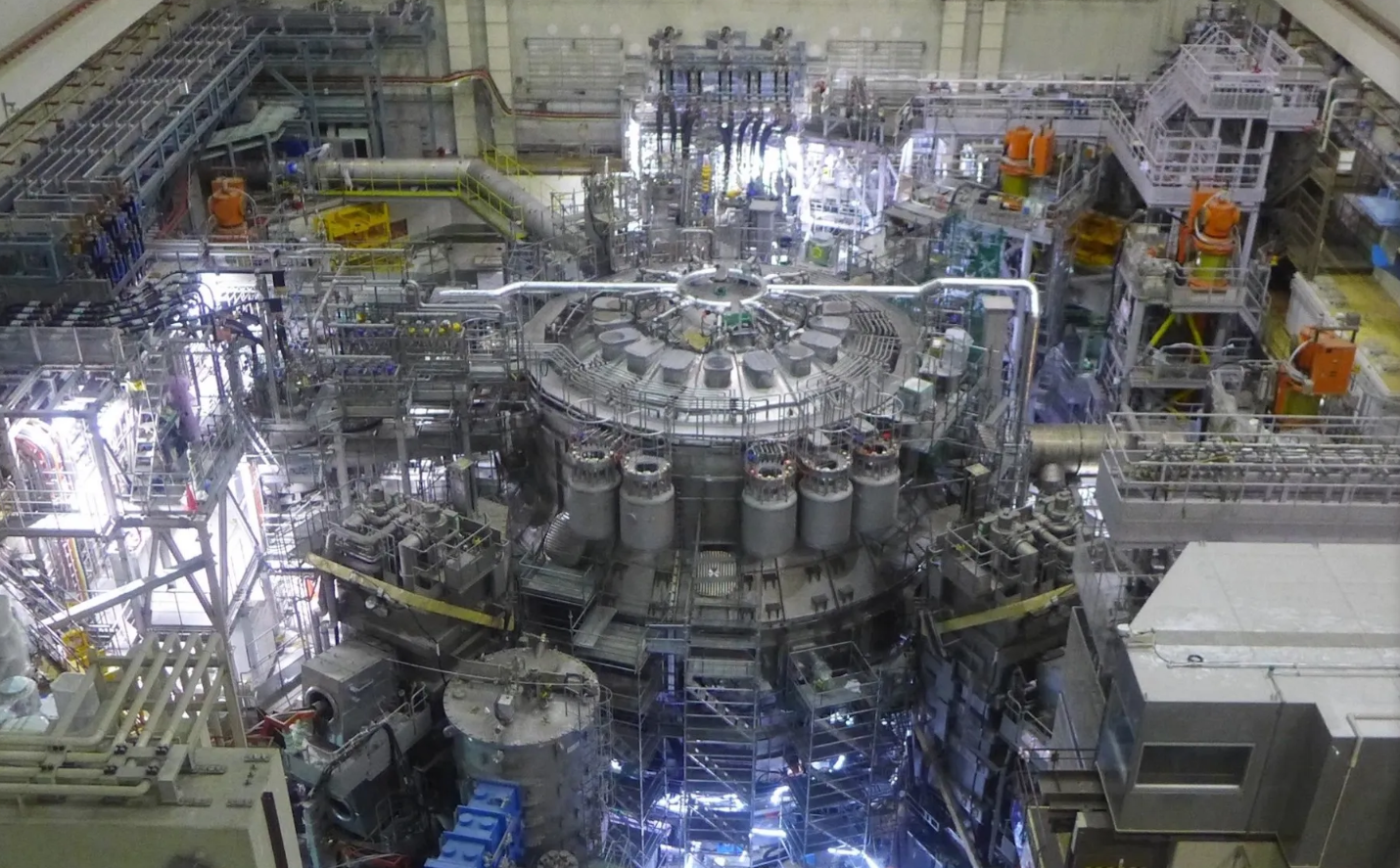

Regarding the potential for nuclear weapons development, Japan’s advanced nuclear power infrastructure and mature spent-fuel reprocessing technology mean that it faces virtually no real obstacles in acquiring nuclear weapons materials. As early as 2013, American scholars Richard J. Samuels and James L. Schoff pointed out that “Japan’s stocks of plutonium now vastly outweigh the amount needed for any plausible nuclear power or nuclear weapons program,” and that the possibility of Japan’s nuclear option “cannot be dismissed.” Another leading weapons expert in the United States, Frank von Hippel, contends that there is “enough plutonium in Japan to make 1,000 nuclear weapons.” In light of Japan's technological capabilities in rocket engineering and aerospace, shock compression and high-speed photonics, its technical potential for developing nuclear weapons cannot be overlooked.

However, for Japan’s far-right groups, the greatest challenge may not be the political decision-making or technological hurdles in the nuclear field but rather the unbearable strategic risks brought about by the geopolitical changes that would follow Japan’s acquisition of nuclear weapons. In fact, even acquiring nuclear capabilities indirectly would bring unpredictable strategic risks to Japan.

The idea and calculations that Japan’s possession of nuclear weapons could serve as some kind of diplomatic and political leverage are equally worthless, as this would be tantamount to adding fuel to the fire, only highlighting their ignorance and superficiality on this issue. In fact, from any perspective, possessing nuclear weapons would not enhance Japan’s security but would instead prove counterproductive, severely undermining the external strategic environment upon which its export-oriented economy relies for its development.

First of all, Japan’s acquisition of nuclear weapons would inevitably trigger significant risks of nuclear proliferation and escalation of nuclear tensions in East Asia. Currently, Asia is the region with the highest concentration of nuclear-armed states globally. Because of complex territorial disputes, historical grievances and geopolitical competition, Asia is also the region with the most complex nuclear deterrence landscape in the world.

After World War II, Japan did not thoroughly address its history of militarism and armed aggression against its neighbors—unlike Germany—and has failed to gain the understanding and trust of neighboring countries. If Japan were to acquire nuclear weapons, it would inevitably prompt other neighboring countries to follow suit, greatly increasing the risks of nuclear proliferation and an arms race, which may not be the outcome Japan truly desires.

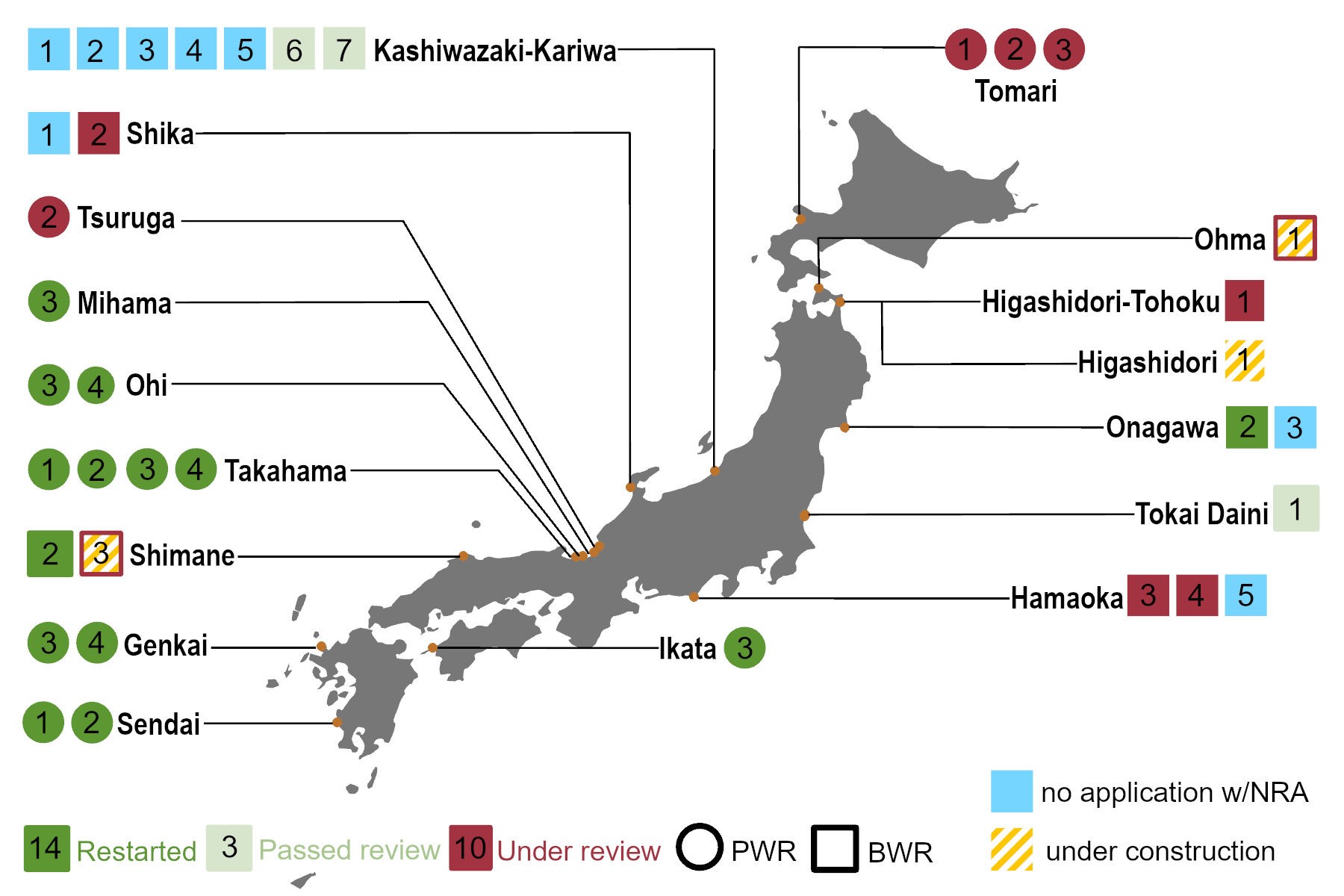

Status of Japan's nuclear reactor fleet (as of January 2025)

(Graphics: U.S. Energy Information Administration)

Data source: Japan Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA); Global Energy Monitor, Global Nuclear Power Tracker; and World Bank

Note: PWR=pressurized water reactor. BWR=boiling water reactor

Second, possessing nuclear weapons would actually increase the risk that Japan would face a nuclear attack in the future. Since the end of WWII, the various “taboos” regarding the use of nuclear weapons that have formed within the international community have served as a firewall preventing the outbreak of nuclear war. Although Japan remains the only nation to have suffered a nuclear attack, its long history of aggression against neighboring countries in modern times—particularly the immense suffering inflicted upon Asian peoples during WWII—continues to impose a heavy moral and historical burden on any attempt at rearmament. Should Japan acquire nuclear weapons in the future, other nuclear powers would face fewer moral and political inhibitions when confronting Japan militarily, making it easier for them to breach the threshold of the “nuclear taboo.”

Third, possessing nuclear weapons would not grant Japan the same international prestige and deterrent capabilities enjoyed by other nuclear-armed states. On one hand, acquiring nuclear weapons would irrevocably erase Japan’s postwar image as a peace-loving nation, and the sympathy and support the international community has extended to it as a “victim” of atomic bombings. On the other hand—even setting aside the vulnerable “window period” that would arise during Japan’s nuclear weapons development—as a densely populated island nation lacking strategic depth, Japan would face heightened vulnerability to any nuclear attack in the future. These factors would significantly undermine the effectiveness and credibility of its nuclear deterrence.

Last but not least, possessing nuclear weapons would also impose incalculable political, economic and diplomatic costs on Japan. Since the 1970s, the international community has established a widely recognized and authoritative non-proliferation regime centered on the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).

For Japan, acquiring nuclear weapons would not only undermine the global nuclear non-proliferation framework but also deal a fundamental blow to the postwar international order—a prospect met with deep concern and strong opposition from both its traditional allies and Asian neighbors. Japan would not only forfeit the diplomatic standing and international advantages enjoyed as a non-nuclear state but also face a series of severe diplomatic crises. The anticipated costs would include, at minimum, diplomatic isolation and resistance from neighboring countries, estrangement and discontent from traditional allies, international sanctions triggered by undermining the nuclear non-proliferation mechanism, and widespread condemnation and protests from global anti-nuclear activists.

Looking at history, the lessons are not far off. Japan has experienced the devastation of nuclear explosions, so it is imperative not only to remain vigilant against the new adventurism and militaristic tendencies lurking behind the fervor and radicalism of proponents of nuclear armaments but also to learn from the historical catastrophe of the past and avoid repeating those mistakes.