Outside this columnist’s residence in Washington, the power centre of the world, are potholes the approximate depth and radius of elephant footprints. President Donald Trump swore to repair such “Third World” blemishes as part of a national infrastructure spree. His Democratic opponents will the same end. Still, two years into his presidency, this most natural of collaborations remains almost unthinkable.

Partisanship is not just a scourge on the civic culture, it is a material nuisance. As well as roads that suggest a pachyderm trudged by while the asphalt was setting, it has shuttered the government for a month now. Mr Trump demands funding for his wall against Mexico. The Democrats, who refuse, are almost as adamant about rights for those who were brought unlawfully to the US as minors. A wall-for-passports deal suggests itself. Few expect it to happen. Neither party values its objective as much as it values the denial of the other side’s.

If the costs of partisanship are unmistakable, its cause has never been. It is modish to blame social media for the information ghettos in which millions enter a stupor of confirmation bias. Others put it down, more prosaically, to uncompetitive Congressional districts, which absolve politicians of the need for votes from the other side. Perhaps, in an atomised culture, partisan fealties have also replaced the church and the union as a source of fellow-feeling.

What few do is to look outside the US for the origin of the problem. The present age of rancour began in the 1990s, the decade of presidential impeachment and the first inklings of the Hastert rule, which required a bill to command a majority of the majority party, whatever its support across the aisle. Now, perhaps it was a coincidence that America’s last challenger, the USSR, had just retired. But I doubt it. Spared outside menaces for the first time in half a century, Americans were free to turn inward and against each other. They re-unified, after the 9/11 attacks, but al-Qaeda was too nebulous an enemy for the effect to last.

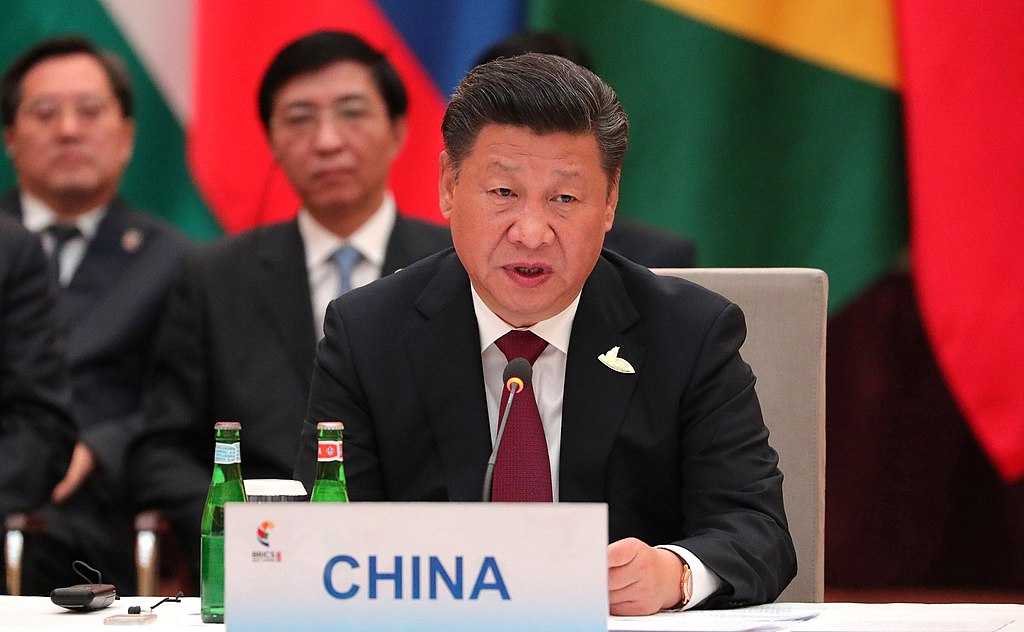

The implication here is bleak and cheering at the same time. The absence of an international rival has been a disaster for the internal politics of the US. And the emergence of a new one, in China, might be an unexpected blessing. For the first time since at least the 1980s, Americans face the kind of economic, ideological and military challenge that can make domestic antagonism seem beside the point, if not unconscionable.

The adhesive properties of external competition have bound otherwise disputatious Americans before. In the early 1800s, the nascent republic was still vulnerable to predatory European empires. It also rubbed up against Mexico on its own continent. Without these outside enmities, a violent showdown over the slave question might have occurred much earlier than 1861. In the 1930s, there was organised resistance to the point of class war against Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Imperial Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor did for that.

Then came the consensus politics of the cold war. It was imperfect. The Vietnam war poisoned the country. But the protests against it were not, strictly speaking, a partisan affair. It was often a case of the left raging against its “own” administrations. And, within a decade of Saigon’s fall, Ronald Reagan was making bargains with Tip O’Neill’s Democratic Congress that now seem scandalously transgressive.

That kind of bipartisanship is a long way off, if it ever comes. But look at the speed with which Mr Trump’s confrontation with China, so shocking in 2017, has found general acceptance, even enthusiasm, not just in Washington but in business. The question is whether this comity will widen to include domestic questions over time. History suggests as much.

Politicians are forever told to be more bipartisan, as though it were a matter of personal agency and nothing else. On this reading, the likes of Mr O’Neill were just better people than today’s rats in a sack. But the international picture matters. It informs the atmosphere in which politics takes place. It determines the stakes. In 1995, the costs of inter-party spite were minimal. The US was the most powerful country in the world by such a margin that it was hard to say which was second. That is less true in 2019. It will be a remote and scarcely believable state of affairs by 2030.

Relative decline on such a gradient cannot leave national politics untouched. The mistake is to assume a negative effect. For all the glory, America’s unipolar moment was no good for its internal cohesion. The end of it is a perverse gift.

janan.ganesh@ft.com

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2019

© 2019 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Please do not copy and paste FT articles and redistribute by email or post to the web.