China’s new rare-earth export controls have turned its dominance in the sector into a powerful strategic tool, extending restrictions to technology, equipment, and expertise that tighten global dependence. The move has intensified tensions with the United States and its allies, highlighting how control over critical minerals now defines the balance of economic and geopolitical power.

While trade relations between China and the U.S. appeared to be on the mend, Beijing announced sweeping controls over the rare earths business sector on October 9, 2025. Within hours, they were followed by American sanctions over a slew of Chinese entities.

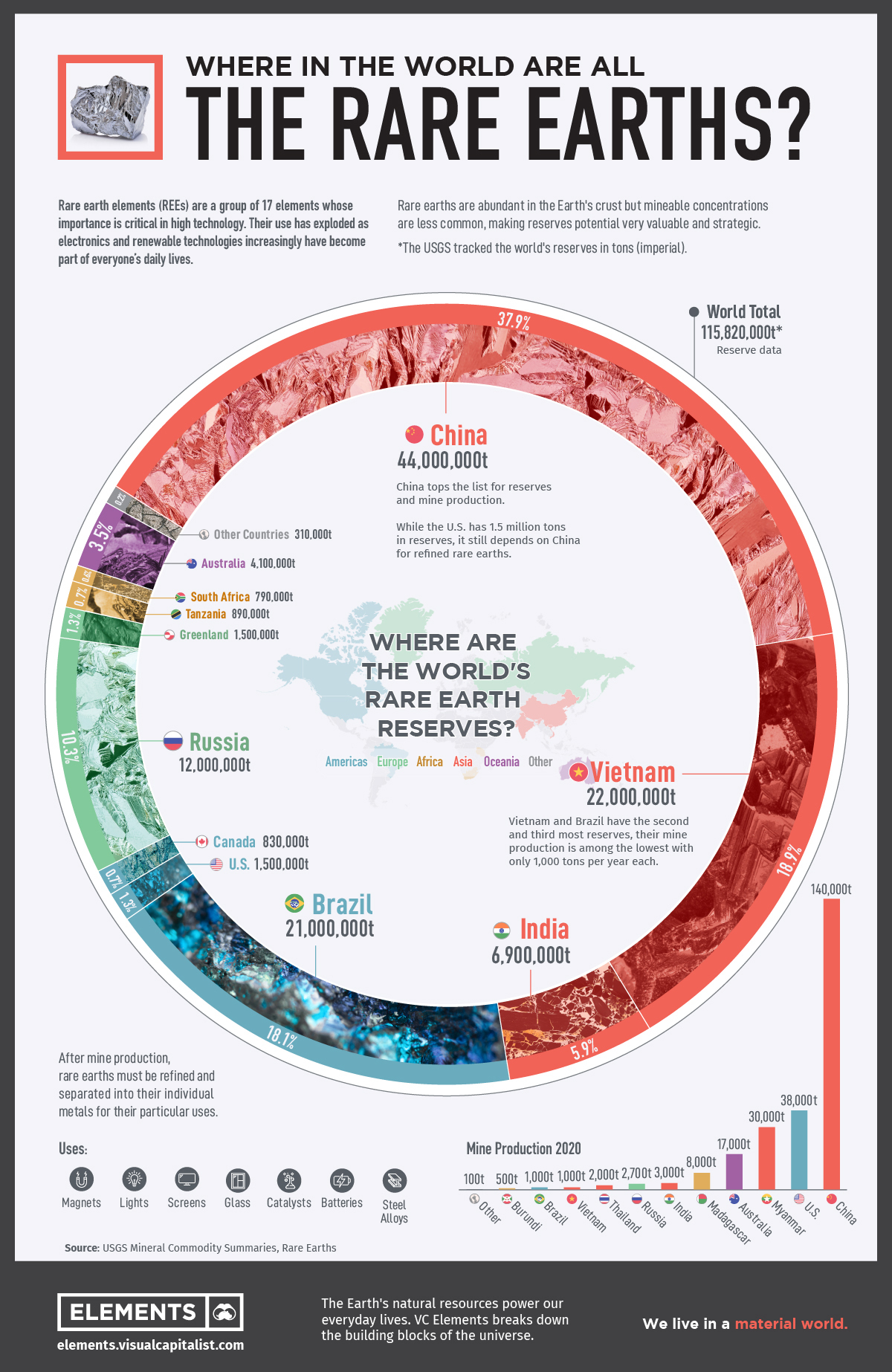

Rare-earth elements (the 15 lanthanides plus scandium and yttrium) are not rare in the sense of scarcity; they are rare because they occur together and are hard to separate and purify. Yet each has unique magnetic, optical or electronic properties that make it indispensable. Their ubiquity across civilian and military technologies gives them out-sized strategic significance — and makes supply-chain control a national-security issue. China has a virtual monopoly over the production and technology of rare earth materials.

Imitating the U.S., China has used the U.S. Foreign Direct Product Rule (FDPR) model under which Washington regulates the sale of foreign made products — if U.S. technology appears anywhere in the supply chain, they can assert jurisdiction.

In order to “safeguard national security,” China issued Announcement 61 of 2025 of the Chinese Commerce Ministry in early October, that rolled out flurry of export controls concerning the rare earth materials. The restrictions extend beyond raw ores to processing equipment, magnet manufacture and recycling technologies, areas where it already dominates. The rules impose licensing requirements on foreign producers if Chinese-origin material, equipment or processing technology was used — a partial foreign-direct-product rule that can reach supply chains anywhere. The notice also explicitly curtails the movement of Chinese expertise: Chinese nationals and companies are barred from providing on-site services in mining, processing or magnet-making abroad without prior permission. Together, these changes make it far harder for other countries to bypass Chinese dominance simply by mining the ores themselves — the provenance of equipment, inputs and personnel now matters as much as where a rock was pulled from the ground.

For a world that depends on these inputs for everything from smartphones to guided missiles, that is not a minor regulatory tweak — it is a strategic lever.

Predictably, Washington responded with a mix of punitive and defensive measures. The White House reacted angrily to Beijing’s move, labeling it a hostile act and announcing heavier tariffs on Chinese goods; at the same time, Pentagon and Defense Logistics Agency initiatives have accelerated stockpiling and procurement of critical minerals and components. The U.S. is also increasing support for domestic processing capacity and sealing partnership pacts with allied producers and processors. Those actions, from tariffs to strategic purchases, are designed both to punish and to reduce dependence on Chinese processing and magnets; but they are costly and take time.

Beijing’s controls are not a bilateral squeeze on the United States alone. By linking export licenses to the use of Chinese equipment or inputs, the rules can hobble European, Asian and African companies trying to build alternative supply chains. The ban on Chinese personnel exporting their expertise prevents the transfer of know-how — so even projects that plan domestic processing will struggle without access to experienced engineers and technicians. The net result is to raise the cost and complexity of diversification: supply chains can be rerouted, but at a heavy cost.

Into this tense, rapidly changing landscape steps Pakistan. In early October Islamabad announced and quietly delivered what it described as the first shipment of enriched rare earths and critical minerals to an American buyer, U.S. Strategic Metals. Photo-ops from Pakistan’s recent Washington visit showed the prime minister and the army chief displaying rock samples to the U.S. president. For Pakistan, the shipment is a commercial and diplomatic opening: a way to monetize natural-resource potential and to court U.S. investment in upstream processing. But it also places Pakistan between two great powers with competing claims and leverage.

Pakistan’s calculus is straightforward and immediate: foreign investment, jobs, and the promise of developing a full mineral value chain at home. But the geopolitical arithmetic is complex. China is Pakistan’s long-standing strategic partner: financier of infrastructure, supplier of military hardware and patron in international forums. China, has for now alleyed any fear of retribution on Pakistan by announcing that Pakistan keeps China aware of its cooperation with the U.S.

Pakistan has an opportunity but must tread carefully. Pragmatism argues for transparent commercial deals with diversified partners, strong governance of resource licensing, and an insistence on building domestic processing capacity that is genuinely independent of single-source dependencies. Islamabad should be candid with both Beijing and Washington about its intentions.

The contest over rare earth is not just about trade balance or headline-grabbing tariffs. It is a competition over the nerves of future economies: electrified transport, high-performance computing, hypersonic weapons, and resilient telecommunications. China’s move exposes the fragility of a world that outsourced not only extraction but the highest-value steps — separation, refining and magnet manufacture — to a single dominant actor. For the United States and its allies, the short-term responses are: tariffs, emergency stockpiles, subsidies for domestic plants and accelerated approvals for allied projects. None of this obviates the need for long-term strategic industrial policy: investment in mining-to-magnet capacity, talent development, recycling, and multilateral risk-sharing mechanisms.

China’s latest rare-earth curbs have transformed a long-running industrial imbalance into a strategic standoff between the sole super power and its most serious challenger. Minerals that were once commodified into bulk exports are now instruments of leverage, diplomacy and alliance politics. If there is one lesson here, it is that technology and geopolitics are now fused in the ground beneath our feet — and nations that want to profit from it must plan strategically, transparently and with an eye to the wider contest playing out between Beijing and Washington.