Picture Credit: Bert van Dijk

What is the impact of the current trade war on the Chinese economy? An analysis shows that while the immediate direct impact on the economy is certainly negative, it is small in real terms, affecting less than 0.5% of GDP. However, while the immediate economic impact may be manageable for China, the trade war itself may do damage to the longer-term relations between China and the United States, including by affecting the future rate of growth of trade in services, including education and tourism. The U.S. has a persistent, large and growing surplus in this area, which was estimated by China to be $54 billion, and by the U.S. to be $40 billion in 2017. The biggest impact from the trade war might go beyond the immediate goods that are affected now.

But first, the immediate impact: the Trump administration’s new list of Chinese products to be subject to tariffs will make the import of most of these goods from China prohibitively expensive for U.S. importers, as they don’t have the kind of profit margins that would enable them to absorb the cost of these tariffs. If fully implemented, these tariffs will effectively lead to a complete halt in affected Chinese exports to the U.S., potentially amounting to $250 billion.

How would that affect the Chinese economy? First of all, China, as a large economy like the United States, has always been relatively immune to external disturbances. During the past four decades, while the rates of growth of Chinese exports and imports have fluctuated like those of all other economies, the rate of growth of Chinese real GDP has remained relatively stable, and in fact has always stayed positive.

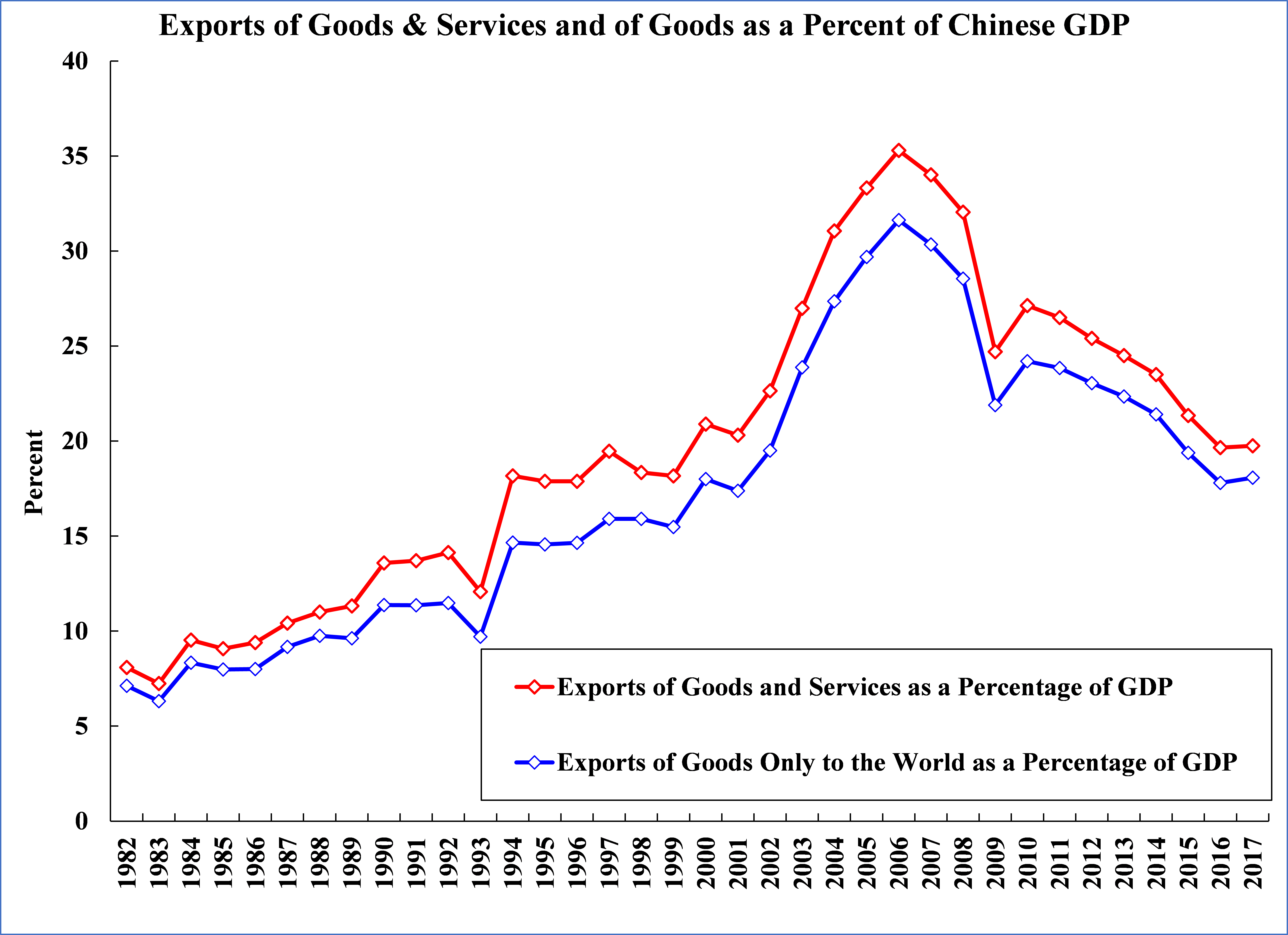

Moreover, Chinese dependence on exports has continued to decline over the past decade. The share of exports of goods within total Chinese GDP has fallen from a peak of 35.3% in 2006 to 18.1% in 2017 (see Chart 1). Specifically regarding exports of goods to the U.S. alone, this share of Chinese GDP has also fallen by more than half, from a peak of 7.2% in 2006 to 3.4% in 2017.

Exports are no longer the principal engine of Chinese economic growth. Instead, the major driver of Chinese economic growth today is its domestic demand, driven by household consumption, infrastructural investments, and public goods consumption.

Chart 1: Chinese Exports of Goods & Services and Goods Only as a Percentage of Chinese GDP

Source: State Administration of Foreign Exchange, the People’s Republic of China.

The fall in Chinese exports as a result of the new U.S. tariffs would amount to 1.7% of GDP. A reduction of this magnitude is material, but quite manageable in the aggregate. Thus, even if all Chinese exports to the U.S. subject to the new tariffs were both halted and not re-directed elsewhere, the decline in Chinese GDP caused would not exceed 1.12%. Such a reduction from an expected annual growth rate of 6.5% would leave 5.4%, which is still a very respectable rate of growth compared to the world average of 3.9%, as projected by the International Monetary Fund for 2018.

Longer-Term Developments

It is important to realize that there are two important longer-term developments simultaneously in play.

First, one of the principal causes of the trade war is actually not trade itself, but competition between China and the U.S. for economic and technological dominance. This competition, whether explicit or implicit, did not begin with President Donald Trump and will not go away even after he leaves office. The “pivot to Asia” and the “Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)”, both policies supposedly meant to contain China, were initiated under President Barack Obama (but seemingly abandoned by President Trump).

This competition could potentially lead to constructive outcomes. For example, the competition to create the fastest super-computer has already resulted in both countries producing better and faster super-computers – the IBM Summit, an American super-computer, is the current world champion, and China’s Sunway TaihuLight, that was built entirely with indigenously designed chips, was the champion in 2016 and 2017. However, the tech war might also stifle innovation through increasingly isolated markets.

The second longer term development is the growth of populist, isolationist, and protectionist sentiment in the U.S. and elsewhere in the world, which will also have significant impact on international trade and investment. President Donald Trump did not create these sentiments, but has been able to tap into and exploit them very effectively.

The biggest problem with a trade war is that there are no real winners — both countries lose because the feasible choices open to each of them are reduced. Exporters in both countries will be hurt because of the reduction in their exports, while importers in both countries will see their businesses decline. Consumers and producers who rely on imported goods and inputs in both countries will have to pay higher prices. A serious trade war, however short in duration, is disruptive as it introduces a great deal of uncertainty in future trade and investment decisions. Moreover, if agreements can be easily overturned and treaties readily broken, long-term arrangements will have little credibility or usefulness.

A better way to narrow the U.S. trade deficit with China would be for the U.S. to increase its exports of goods and services to China, especially newly created goods and services, such as food and energy. Chinese demand for food and energy will continue to be high and rising for many years. These transactions would lead to genuine increases in GDP and employment in the U.S. and economic well-being in both countries.

Another fast-growing component of U.S. exports of services to China is education and tourism. The expenditures of Chinese students (currently totaling 350,000) and tourists in the U.S. have been rising rapidly. Moreover, their presence in the U.S. can enhance understanding between the Chinese and American people and improve long-term ties. U.S. students and tourists in China can also play the same role.

Through trade and cultural and educational exchanges, it is possible to promote further economic interdependence between the two countries. China could become the largest customer of U.S. energy, food, and educational services exports and the U.S. could become China’s most important supplier in these areas. Both countries can win.

When Will the Trade War End?

Since the trade war is lose-lose, it is in the interests of both China and the U.S. to try to end it soon. However, it is not likely to end before the upcoming U.S. mid-term elections on November 6, as President Trump needs to be able to declare a victory in the trade war, and likewise, for President Xi to maintain that China has not capitulated to U.S. pressure.

There are also longer-term underlying forces at work in China-U.S. relations. We can assume that the ongoing competition between China and the U.S. – whether friendly or unfriendly – will persist for the long-term. It is difficult to predict how things will end up. China and the rest of the world, except possibly the U.S., will likely continue to uphold the current multilateral trading system under the World Trade Organisation (WTO), as they have all benefitted and will continue to benefit from it.

In spite of uncertainties and tension, it is in the interest of both Americans and Chinese to promote greater mutual economic interdependence between our two countries.