Click to read China-US Focus Digest VOL 27

Great power conflict is now in full force, and an about-face is out of the question, regardless of the outcome of the US elections. But whoever will assume office in Washington can certainly shape and direct how the US-China rivalry will play out. Apprehension about policy continuity hindered other countries’ engagement with the US in the lead-up to US election polls. Calibration may come about as a new US leadership emerges and sets out its foreign policy for the next four years.

President Donald Trump’s “America First” put multilateralism and globalization on the backseat, unsettled alliances, and undercut America’s global brand. The imposition of tariffs to foes and friends alike invited retaliation from rivals and take partners aback. Steep demands for allies to pay more and deriding what he sees as freeloading scuttled decades-old treaty alliances and sent a chilling notice to emerging security partners. The ascendance of economics and transactionalism raised concerns about Washington’s commitment to values promotion. The incumbent leader’s policies were described as disruptive and erratic, criticisms that are likely anchored on his rhetoric as policy documents his administration released, and actions taken in line with the same suggest the presence of a broader, though mostly security-oriented, strategy.

Trump’s preference for bilateral trade deals may deprive the US a seat in shaping the future of mega-regional trade pacts, including the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, whose predecessor (TPP) was championed by the US under Obama. This said, the success of renegotiating NAFTA into USMCA may provide the spark for Trump to remake multilateral trade deals, although twelve countries at varying stages of development are hardly comparable to three contiguous neighbors with less-pronounced economic disparities. His trade and tech war interrupted supply chains and sent jitters to global markets already in the doldrums because of COVID-19. His domestic coronavirus response blew the US image in dealing with health crises and weakened Washington’s position not only in fostering world economic recovery but also in any possible global reordering post-pandemic.

Trump’s first term presents the growing US dilemma - keeping its primacy in a period of rising ambitious powers but showing reluctance in sustaining that greater share in public goods provision that made it the recognized system leader. This predicament will only become more acute in his second term.

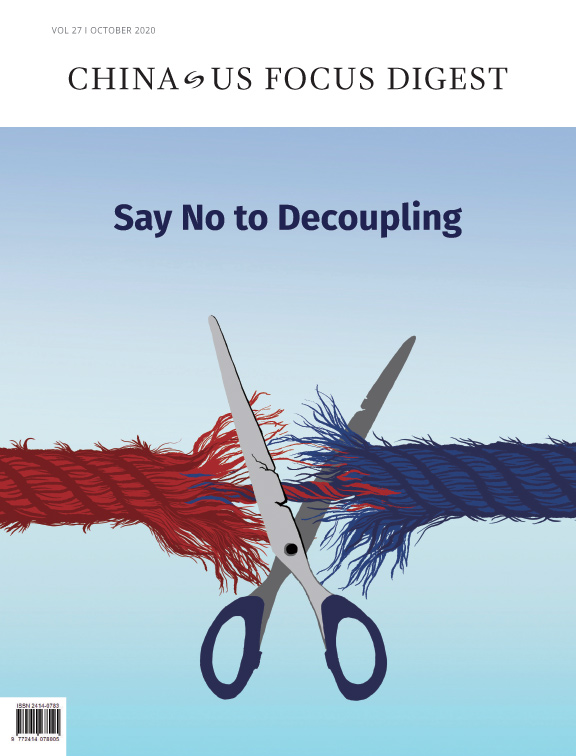

Former Vice President Joe Biden may augur a return to a more familiar and predictable US foreign policy. He is likely to recommit the US to multilateralism – reversing Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris climate accord, the World Health Organization, and UN Human Rights Council, pulling back from threats to leave the World Trade Organization and resuming funding for the UN Relief and Works Agency. He expressed readiness to rejoin the Iran nuclear deal if Tehran will take steps to demonstrate the commitment to the P5+1 deal reached during the Obama-Biden government. He may reinvest more in US diplomacy, manage alliance issues better, and pursue more targeted sanctions with identified goals. He may limit decoupling to critical supply chains and continue diversifying away from Beijing while promising an easing of sanctions dependent on improvements of market conditions and the human rights situation in China. His commitment to democratic renewal at home and abroad – promising to host a summit of democracies in his first year in office - will face headwinds overseas given the growing clout of autocracies and the rising tide of illiberalism. Whether these actions are enough to shore up US credibility and regain lost ground is another matter. If Trump’s moves are indicative of global leadership fatigue and mounting desire for a domestic refocus, Biden’s foreign policy aspirations may be moderated by constraints from the home front.

While both try to project resolve and toughness in dealing with the challenge posed by China, the two candidates harbor different views on how best this can be carried out. The Trump administration elevated China as the central challenge for the US, made great power competition the key organizing principle of US security and foreign policy, widened the domains for contest and saw tariffs, sanctions, and decoupling as means to redress the trade imbalance, upend unfair trade practices and ground its rival. The competition was also portrayed along ideological lines. China’s threat to a rules-based order was stressed and responsibility for the coronavirus was placed on its doorstep. Although belated and perhaps more election-poised, efforts to marshal nations – from Europe, ASEAN, and Quad - to oppose China’s actions in anywhere from Hong Kong to the South China Sea were made. The breadth of disagreement between Washington and Beijing left few spaces for cooperation. The fulfillment of Phase 1 of the trade deal, the implementation of which was impacted by the pandemic, may offer some respite and may build momentum for a Phase 2. Whether mutual confidence gained in trade can help dial down tensions in other areas remains to be seen.

Biden, in turn, has not explicitly put China in the same spot as Trump has, although China will undoubtedly also loom large on his agenda. But placing democracy at the center of Biden’s foreign policy may make his challenge to Beijing more fundamental and, in a way, push Beijing to resonate more with the Trump administration’s rhetoric. This may portend greater pressure on Beijing over Hong Kong, Xinjiang, Tibet, and expression of dissent elsewhere in China. But instead of America going it alone, as he criticized Trump for, Biden will leverage the US enduring alliances and partnerships to rein in China. However, building coalitions now are more complicated than before as the national capacities, demand for an agency, and desire to hedge against uncertainties have increased among middle and small powers.

Furthermore, the flames of nationalism and heightened sensitivity to what may be taken as domestic interference make conversations on human rights hard even among longstanding allies and friends. This may have prompted Trump to be less intrusive on such issues in the interest of creating a coalition against China. Whether Biden will tolerate this arrangement may hinge on how he sees the challenge posed by China in the order of threats the US and the world faces. This said, despite stark differences, areas for bilateral cooperation exist. This includes pandemic response, climate change mitigation, arms control, nonproliferation, denuclearization of the Korean peninsula, and even counter-terrorism and anti-corruption.

Regardless of who wins, the US, more than upholding values, should also give high priority in presenting alternatives. If it wants to wean countries away from state-backed infrastructure finance like China’s Belt and Road, it has to show that a private-sector lead counterweight can work and within reach. More than exposing the security vulnerabilities of Chinese tech companies like Huawei, it has to offer viable substitutes to countries raring to enter the Fourth Industrial Revolution or, at least, partake of the benefits of 5G. Beyond warnings, options, and mitigating measures are critical as countries invest to enhance their competitiveness. Moreover, even in the promotion of values, the US has to thread the balance between supporting basic individual rights and respecting how other countries organize their societies. This is a crucial line that should not be lost lest the US be seen as imposing its values and ignoring the diversity of political and governance models among the community of nations.

The stakes for this coming election have never been higher for America and its place in the world. While its military advantage is still close to none and its soft power remains immense, it cannot rest on these two alone. Growing aspirations of rivals and the struggles of developing countries blazing their own developmental paths will test America’s quest to remain a leader in a rapidly changing world.