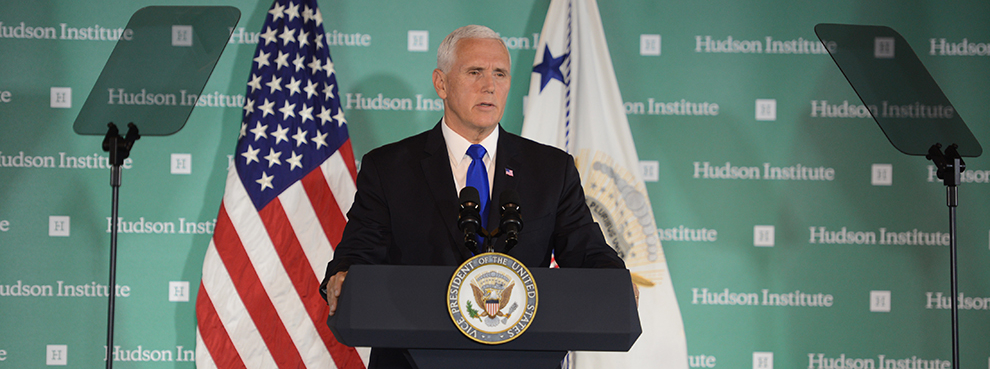

Vice President Mike Pence’s speech at the Hudson Institute on October 4, 2018 includes a laundry list of complaints and the beginnings of an action plan, but on its own it hardly represents a strategy. If we look at his remarks together with two major strategy documents that preceded it, however, a clearer outline of Trump’s China policy begins to emerge.

Anthony Cordesman at the Center for Strategic and International Studies talks about the U.S.-China relationship in terms of four “Cs”: Conflict, Containment, Competition, and Cooperation. While he acknowledges that some competition between the two states is necessary, he argues that in other areas, cooperation offers more benefits for both. What concerns him about the current situation is that “it is becoming steadily harder to distinguish between efforts designed to limit or contain the other state and those that might lead to actual conflict.” The concept of the four Cs offers a useful way to conceptualize international relations, helping us to address the inherent complexity of great power interactions. Successful statecraft can be seen as finding a balance amongst them, choosing the right one at the right time.

Until about the mid-2010s, the U.S. has been guided by grand strategies that relied mainly on cooperation when it came to China. Cooperation meant attempting to integrate China into the institutions, norms, and values of the liberal global order the U.S. had built, a mission that included bringing China into global multilateral institutions such as the UN, the IMF, the WTO, and the G20. The end game was preservation of this liberal order, a win in which the U.S. saw its own national interests best protected. And if China wanted to fully embrace Western ideals and values as a result, well, that was a bonus.

It should be mentioned that the third “C” of containment did also manifest. For example, to this day the U.S. and the European Union refuse to grant China Market Economic Status.

While conflict seemed possible, tensions never culminated in violence, despite episodes such as the 1995-1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis or the 2001 EP3 incident in Hainan. Because both took place within an overall atmosphere in which cooperation was the dominant approach, the option of de-escalation remained not only viable but preferred in order to maintain the status quo.

But under Trump, cooperation is no longer the favored option. Today is all about competition with China.

The National Security Strategy released by the administration in December 2017 states explicitly that we exist in a competitive world and that U.S. strategy is to compete successfully across multiple contests that exist in the military, economic, and political spaces. The NSS not only embraces the concept of competition but goes so far as to suggest that cooperation is ineffective:

“These competitions require the United States to rethink the policies of the past two decades—policies based on the assumption that engagement with rivals and their inclusion in international institutions and global commerce would turn them into benign actors and trustworthy partners. For the most part, this premise turned out to be false.”

Rather, “An America that successfully competes is the best way to prevent conflict.”

China (alongside Russia) is identified as a prime competitor to the United States and the NSS perceives this competition in zero-sum terms, with China eroding U.S. interests and expanding its own influence: “China seeks to displace the United States in the Indo-Pacific region, expand the reaches of its state-driven economic model, and reorder the region in its favor.”

Similarly, the National Defense Strategy that followed in January 2018 is unequivocal about the importance of competition: “Inter-state strategic competition, not terrorism, is now the primary concern in U.S. national security.” This strategy involves directly expanding the competitive space, where “we continue to offer competitors and adversaries an outstretched hand, open to opportunities for cooperation but from a position of strength and based on our national interests.”

The vice president’s October 4 speech develops these defining ideas, suggesting that not only did cooperation fail to bring China into greater partnership with the U.S. and the world, it actually allowed China to choose “economic aggression, which has in turn emboldened its growing military.” Pence also emphasized the zero-sum nature of U.S.-Sino competition, not just in the economic space, where he said China’s manufacturing base was built at the explicit expense of the U.S., but also in the arena of military competition, where he alleged that China “wants nothing less than to push the United States of America from the Western Pacific and attempt to prevent us from coming to the aid of our allies.”

Given the zero-sum view that many in Washington hold, it is essential that others who maintain a role in setting and implementing U.S. policy towards China do not forget that the cooperative space and the institutions of the liberal world order can help ensure that escalation into conflict is neither accidental nor inevitable. De-escalating a trade war may not require the WTO, but couldn’t the meeting during the G20 between Presidents Trump and Xi foster face-saving and meaningful agreement in part because of the multilateral context?

Further, the upcoming ASEAN and APEC summits also offer important fora where the administration should engage with China on hot-button security issues, such as the South China Sea. Such discussions should not just occur bilaterally, but also within the larger multilateral community, where cooperation could be found on agreeing to a Code of Conduct, for example.

The Sino-U.S. relationship is complex and multilayered and demands a similarly robust statecraft. Competition can and should be a healthy part of this relationship, but it should not be the only tool in the Administration’s toolbox. Engaging China through a mixture of competition and cooperation could mean the difference between a sustainable bilateral relationship and a tension-ridden set of exchanges careening toward conflict.