The U.S. president’s strategic shift is not temporary. It represents a medium- to long-term trajectory that stems from the confluence of simmering contradictions and various domestic and international factors.

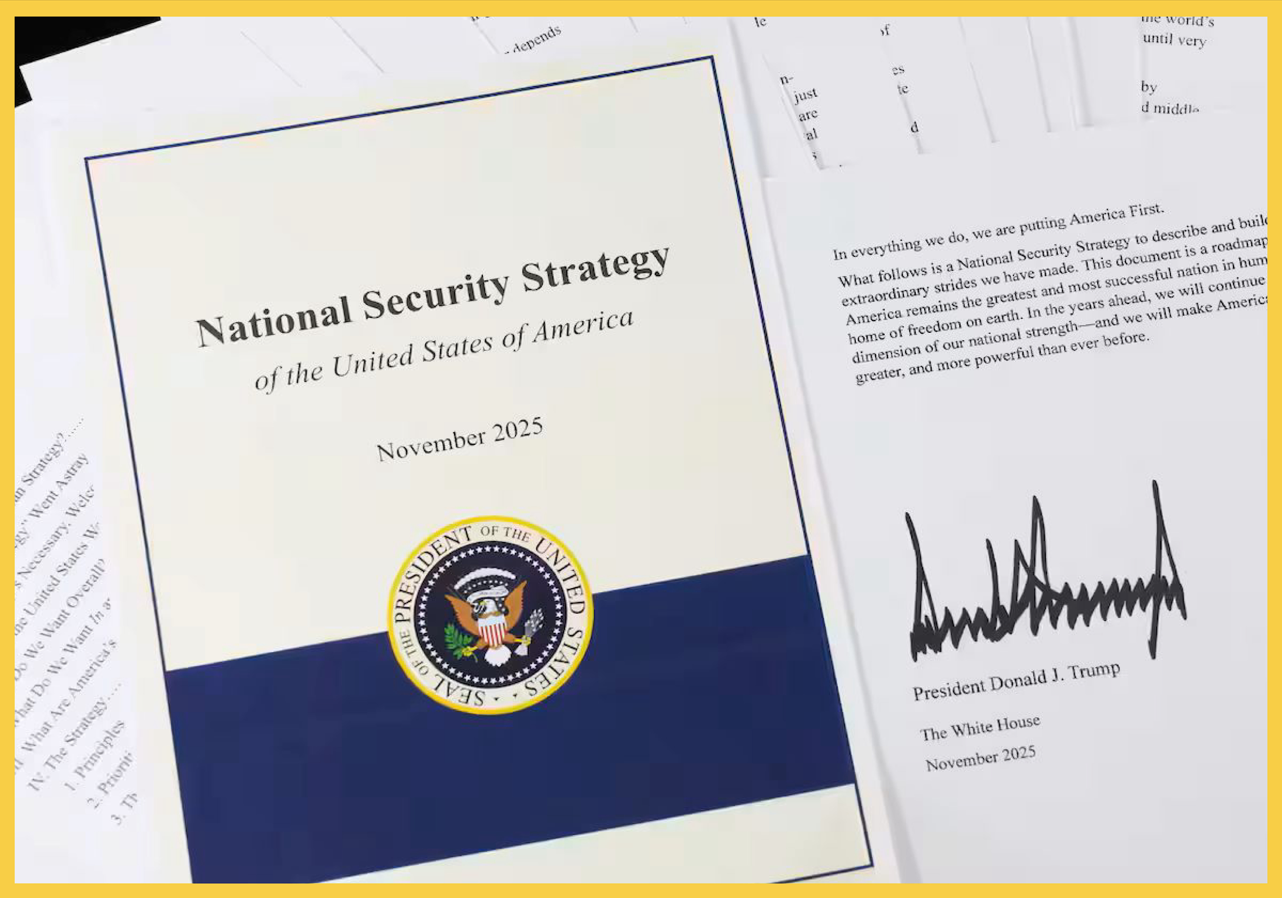

The administration of U.S. President Donald Trump has aggressively pursued his “America first” policy since he took office. In its recently released National Security Strategy, the administration rejected the notion of permanent American dominance over the entire world. Yet the U.S. military seized Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro and withdrew from 66 international organizations whose operations were seen as contrary to America’s interests. These moves underscore a clear shift: the United States is now turning inward, asserting control over the Western Hemisphere, as part of a global retrenchment strategy.

The administration is reorienting its strategy and resources accordingly, guided by conservatism, introspection and retrenchment. It pursues practical interests from a position of strength and seeks to replace liberal internationalism with ethno-populism. Globally, it rejects multilateralism, dismisses the United Nations and other international institutions and has withdrawn from global commitments. It demands more responsibility-sharing from allies in Europe, Japan and South Korea, pressuring them to increase defense spending and pay for U.S. military protection. Geopolitically, it prioritizes dominating the Western Hemisphere and maintaining deterrence in Asia, and it seeks to disengage from conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East. It favors quick, surgical strikes with limited engagement and manageable costs, avoiding protracted wars. It also downplays ideological factors such as the promotion of democracy.

There is a common belief that this strategic retrenchment will not outlast Trump’s term. Any other subsequent president, Republican or Democrat, will return the U.S. to a path of hegemonic expansion. This is probably misguided. In the long arc of history, U.S. foreign and security strategy have swung between isolationism and globalism.

In the late 18th century, the U.S. embarked on a path of isolationism that lasted for more than a century, triggered by President George Washington’s farewell address, which championed the avoidance of foreign entanglements. In the first half of the 20th century, the U.S., after being embroiled in two world wars, eventually turned away from isolationism and led the West, paving the way for globalism for nearly 80 years. Since Trump began his second term, he has disruptively dismantled the policy adjustments of his predecessor, Joe Biden and greatly amplified presidential power to new levels. Trump marks a true return to isolationism and nationalism.

Overall, Trump’s strategic shift is not temporary. It represents the start of a medium- to long-term arc that stems from his confluence based on simmering contradictions and various domestic and international factors. The attempt to purchase Greenland for territorial expansion is an exemption rather than the norm, and it doesn’t alter the overall strategy of global strategic retrenchment.

First, the United States is finding it increasingly challenging to sustain its global hegemony. Since World War II, and especially in the decades following the Cold War, it has engaged in extensive global expansion, which has gradually stretched its strategic resources thin. Dysfunctions are becoming ever more evident in its political, economic, and social systems. The economy has grown increasingly reliant on the financial sector, while manufacturing has declined and fiscal sustainability has become more dubious.

Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, has repeatedly cautioned that the U.S. is in a period of hegemonic decline, marked by dysfunctional state institutions and even the risk of internal strife akin to civil war. In essence, the United States has transitioned from an unassailable superpower to a crippled giant. Although it maintains strengths in finance, technology and the military-industrial complex, the country can no longer perpetuate its earlier model of expansion.

Second, the domestic consensus for global expansion has collapsed. Since the 2008 financial crisis, domestic interests have become increasingly polarized, divided by clashes between globalists and nationalists, multilateralists and unilateralists, and between supporters and opponents of globalization.

The unchecked growth of capital globalization has widened the wealth gap, with the rich reaping most of the benefits. The broad middle and lower classes have lost out. This has given rise to the pain of the Rust Belt, the lament of “Hillbilly Elegy” and the so-called “kill line”—people living paycheck to paycheck. Consequently, the middle class has shrunk, but delivered strong public support for “America first,” reversing the decades-long trend of globalism.

Both the Biden administration’s “foreign policy for the middle class”—which emphasizes putting the needs of working families at the core of national security, as well as the Trump administration’s formal National Security Strategy, which states that “misguided and destructive bets on globalism and so-called free trade hollowed out the middle class and industrial base”—reflect increasing domestic economic pressures. It is squeezing the space for foreign policy. Reducing overseas expenditures and increasing domestic investment have become a bipartisan consensus.

Third, the United States now deems MAGA’s prioritization of domestic affairs as the key to great-power competition. A nation’s power strategy is shaped by both internal factors—national strength and interests, history, culture—and external factors such as the global environment and state rivalries. During the Cold War, the U.S.-Soviet rivalry was marked by military and geopolitical competition that drove both sides to build vast nuclear arsenals and carve out spheres of influence. Eventually, the arms race tipped the balance of power. Today, great-power competition largely depends on national strength underpinned by technological advancement and industrial upgrading.

Initially, Trump attributed America’s problems to China. However, by his second term, he and the U.S. strategic community acknowledged that America’s challenges are largely self-inflicted and recognized China as an and balanced rival without precedent. Consequently, the U.S. grand strategy now centers on enhancing its hard power in the economic and technological domains. Its efforts to lead in artificial intelligence and secure global critical minerals and other advantages are integral to this approach.

As the two largest economies, China and the United States will shape the international order together and influence each other’s strategic options. Some pundits argue that the U.S. is becoming more like China and China is becoming more like the U.S.

It is important to note, for now and the foreseeable future, that while the U.S. may no longer be the global hegemon we have known, it remains the preeminent power among the majors. Strategic retrenchment is relative and has been influenced by many of Trump’s personal penchants and whims, which have already caused a backlash and will likely be recalibrated over time. Undoubtedly, great powers have special international responsibilities.

The United States needs to fine-tune its role in a multipolar world, delineate reasonable boundaries that match its strengths, interests and responsibilities and achieve a new balance in its relations with the world. This approach will neither be solely a globalist expansion aimed at maintaining the liberal international order nor the isolationist and nationalist posture advocated by the MAGA faction. After all, the world still needs the United States, and the United States needs the world even more.