Arbitrary policies introduced by the U.S. president have accelerated a shift of the international order and introduced new dynamics to relations between major powers. Most countries are reluctant to follow Trump’s lead because they have little to gain by doing so. Several are quietly thinking about ways to turn his disruptions into opportunity.

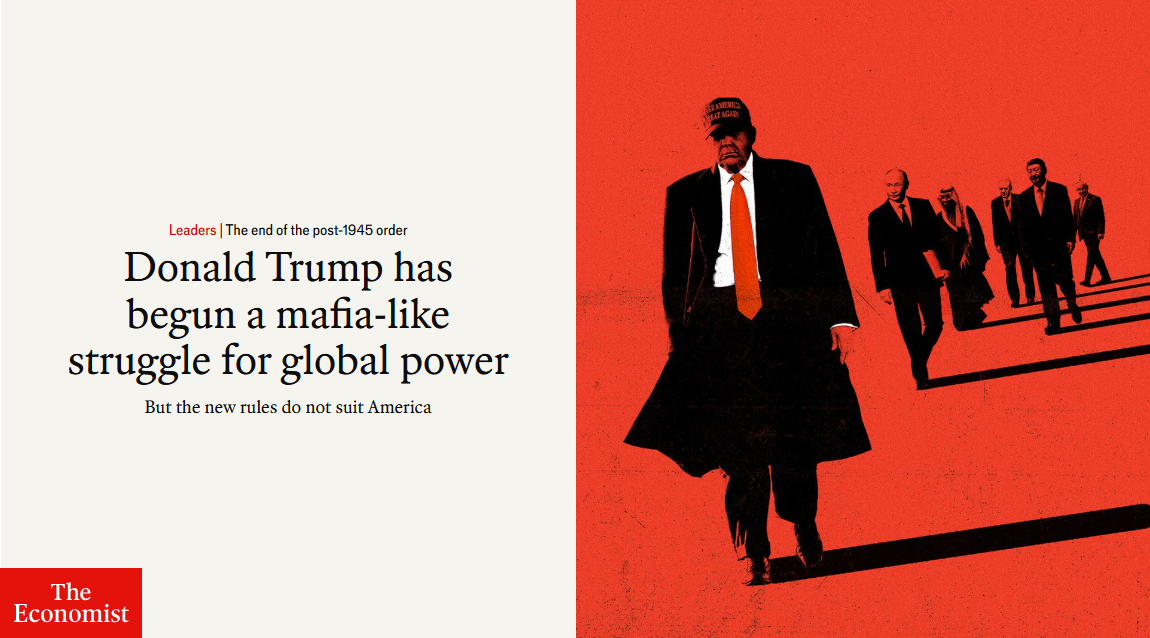

Photo: The Economist cover

Global observers for months have hoped to pin down Donald Trump’s grand strategy, but apart from a clear tendency toward deal-making and uncertainty, the U.S president has not convincingly shown anything. He has, however, implanted a new world view in the United States, one centered on the belief that the U.S. is in decline (hence the need to “make America great again”), largely because of its long-standing foreign policy. In other words, despite having led the world order for decades, the United States has gained little from its dominance and should look to its own inner problems.

Trump’s new policies have accelerated a shift in the international order and introduced new dynamics into the relations of major powers. First, interactions have become highly fluid. Since January, when Trump took office, to early April the American administration has focused mainly on resolving the Russia-Ukraine and Palestine-Israel conflicts through diplomacy. This shift in Washington’s priorities made the greatest impact on its traditional allies, while Russia appeared to be the biggest beneficiary.

From early April onward, a trade war has become the centerpiece of Trump’s foreign policy, with a China-U.S. confrontation rapidly heating up. Previously, Trump had made many gestures of goodwill toward China, and observers believed there were two possible trajectories for Sino-U.S. relations. Washington might focus on countering China after pulling back from Europe, or it might try to negotiate with major powers, such as China and Russia, to jointly manage world affairs. With the Trump’s trade war, however, the first scenario has become increasingly likely. Meanwhile, interactions between China, the United States, Europe and Russia have been intensified, drawing close international scrutiny.

Second, the foreign policies of major non-hegemonic countries have had a stronger and broader impact than before. Before the Spanish prime minister’s visit to China, for example, U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent warned the EU not to move closer to China, saying that it would be tantamount to “cutting your own throat.” Meanwhile, the United Kingdom and other major European countries, especially France, have explored new models of cross-Continent cooperation, including building a volunteer alliance to support Ukraine as part of an effort to turn Europe into a strategic pillar of the evolving international order. After Trump’s inauguration, certain Western powers — the EU, the United Kingdom, Canada and Japan — also stepped up communication and cooperation, aiming to collectively mitigate the negative impact of Trump’s policies. For its part, China regards the BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation as tools for dealing with the turbulence triggered by Trump.

Third, countries are now pursuing negotiations marked by strategic hedging on multiple fronts. On one hand, the United States seems intent on withdrawing from world affairs, but it remains at the center of the international order. That explains why most countries still hope to maintain positive communication with Washington. Judging from current economic trends worldwide, the United States remains poised to be the next serious leader on the global stage. As such, a new international order can take shape only after it gets its own house in order. No other country seems able to provide an alternative. In fact, there is no anti-American bloc at present. Analysts still define a country’s global position in terms of its relationship with the United States. On the other hand, countries are reluctant to act in line with Trump’s new policies. Their responses can be roughly divided into four categories:

• “Resistance,” with China being the most typical example, followed by Canada and the European Union;

• "Coaxing,” as seen in the behavior of the United Kingdom, India and Japan;

• "Procrastination,” as adopted by Russia, Ukraine and Iran; and

• “Waiting,” as illustrated by North Korea.

Of course, many countries use all four approaches at the same time. In general, they are vigilant and stand ready to minimize their losses in dealing with the Trump administration. Virtually no one actively promotes Trump’s agenda, and several major countries are quietly thinking about ways to turn the disruption into an opportunity.

Fundamentally, most countries are reluctant to follow Trump’s lead because they see little to gain by doing so. They base their position on the belief that the United States is in decline, even though, paradoxically, the U.S. president is attempting to use raw power to pressure other countries. In fact, the Trump administration has adopted a tough stance with respect nearly every country in the world. Other than a handful countries (Israel and Russia, for example, even though their benefits remain uncertain), virtually no state has benefited from Trump’s diplomatic shifts. Even those governed by right-wing populist politicians, such as Hungary and Italy, which originally had high hopes for Trump, have seen little payoff.

Moreover, for many countries, Trump’s policy shifts have been unacceptably abrupt. Previously, their development models were adapted to some extent to the U.S.-led global order. For instance, Chinese goods mainly supplied the American market, and European integration was seen as the embodiment of economic globalization at the regional level. Today, however, Trump is attempting to use high tariffs to protect domestic industries, catching all major trading countries off guard.

Trump’s hostility to regulation and environmental protection raises difficulties for members of the European Union — top performers in both domains — to agree with Trump’s policies. Although some major countries have tried to adjust in various forms, their development models, which are deeply rooted in domestic realities, cannot change overnight.

More important, Trump has not presented any new blueprint, despite his moves to dismantle the old international order. A typical example is his attempt to resolve the Russia-Ukraine conflict without addressing the broader question of European security. The daily operation of the international community depends on basic systems, and so many countries have spontaneously maintained the old order to some extent. In recent months, for example, the EU and China have accelerated efforts to finalize trade agreements with other major partners.

On Feb. 24, the third anniversary of the Russia-Ukraine conflict and the start of U.S.-Russia talks on the issue, most of the UN General Assembly voted in favor of a resolution drafted by Ukraine and the European Union. By advocating systems and rules beneficial to themselves, major countries and blocs hope to secure a greater voice in the future international order.