Excerpt from The Obliteration Doctrine

Since fall 2023, Israel has engaged in genocidal atrocities in Gaza. So, why hasn’t the Genocide Convention been used to preempt the violence? Why has the Convention proved ineffective since its creation? The West’s long struggle against the Genocide Convention is one of the central questions of Dan Steinbock’s new book, The Obliteration Doctrine.

The International Criminal Court’s (ICC) track record in the past two decades suggests a substantial gap between its broad mandate and very limited resources and state support. There is a sharp difference between the activities of the ad hoc tribunals and the ICC.

In the case of the tribunals, influential governments, mainly the permanent members of the UN Security Council, while committing time and funds to backing what they perceive as international justice, have focused on selected conflicts based on their national interests. Led by the United States, the countries bankrolling these tribunals supported them politically and militarily.

But it hasn’t been a free lunch. Leaning on mainly the West, the victors of 1945, this cooperation generated results, but it made the tribunals highly reliant on U.S. political support, intelligence and NATO-led forces.

The implementation deficit

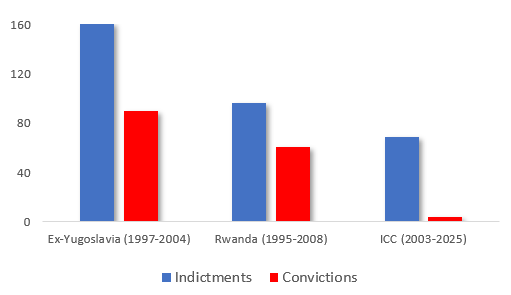

The Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia convicted nearly 90 individuals, including senior political and military officials. Similarly, the Rwanda Tribunal ultimately convicted more than 60 individuals, almost two-thirds of those charged with crimes.

Even though the ICC itself has extensive jurisdiction, it has weak political support. For this reason, the Court seems to have moved cautiously when it began operations in 2003. It acted when the country in question explicitly requested court intervention (Congo DR, the Central African Republic, Uganda) or when the UN Security Council authorized the role of the court.

However, this pattern changed around 2010, when the ICC Prosecutor launched an investigation in Kenya. It was the first undertaken without explicit state support.

In the subsequent years, the ICC initiated several investigations that led it to be contested by several non-member states, including Russia (Georgia, Ukraine), Libya, Myanmar, US (Afghanistan), and Israel (Gaza). In the process, the number of active investigations soared to 17, but the results, at least in terms of trials and convictions, were few.

In over more than 20 years, the Court has secured convictions in just 4 cases, and most of its arrest warrants have been without effect. Compare that with the former Yugoslav Tribunal’s track-record of 161 indictments, 90 convictions and sentences in less than seven years.

Ad Hoc Tribunals and the ICC: Indictments and Convictions

SOURCE: The Obliteration Doctrine (data from ICTY, ICTR, ICC)

Strings attached

In several ICC cases, such as Sudan, Libya, Palestine, Burundi, Myanmar, and the Philippines, the prosecutor has lacked access to the territory in question or faced significant obstacles in taking investigative steps in the country. The ICC Kenya case, which occurred without explicit state support, is illustrative. After three years, the ICC charges were dropped in 2015 for lack of evidence.

Yet, the track record of the ICC shows it can be quite effective when prosecution has strong political backing. When the primary funders of the ICC and most permanent members of the UN Security Council have been in consensus, the Court’s implementation capacity has been boosted by abundant resources, as evidenced by the ICC arrest warrants for Russian leaders in 2023–24.

The warrant against Russian President Putin was the first against the leader of a permanent member of the UN Security Council. Unsurprisingly, the ICC enjoyed maximum cooperation and resources in Ukraine. Then again, as the Trump administration initiated its peace talks between Russia and Ukraine in spring 2025, the ICC’s role was largely ignored.

Given its current trajectory, the ICC is likely to continue to go after a few high-profile cases. In those that are aligned with the interests of the West, the Court’s ambitious rhetoric is more likely to be backed up with adequate resources and boosted implementation. But in other cases, the colossal gap between stated objectives and actual achievements weakens the prospects of prosecution.

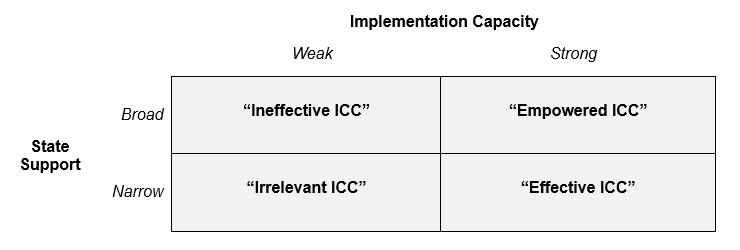

Four ICC scenarios

In principle, there are four possible ICC scenarios, based on state support and implementation capacity. When the Court has broad support and implementation is strong, it is truly empowered. Such an ICC has not existed yet and is unlikely to exist in the foreseeable future because the national interests of its constituent member-states tend to trump the Court’s universalist predilections.

When the ICC has narrow support but strong implementation capacity, it can be quite effective, as evidenced by the ad hoc tribunals (or the model the U.S. initially proposed to the Court). In this scenario, things get done but outcomes reflect self-interested policies vulnerable to allegations of politicization.

The current ICC seems to represent a reverse scenario. When nominal broad support is coupled with weak implementation, the ICC is likely to prove ineffective; high on rhetoric, but weak in execution.

The worst scenario would be a Court with both diminished state support and low execution capacity. Over time, it would translate to irrelevance. Distressingly, in the absence of major changes, this is where the current ICC may find itself, if the ongoing geoeconomic and -political divides continue to penalize global prospects.

Four Scenarios

SOURCE: The Obliteration Doctrine

ICC’s untenable position

Obviously, great powers, particularly the permanent members of the UN Security Council, seek to influence such scenarios. As a result, the current ICC, overshadowed by its great ambitions but weak implementation capacity, is in an untenable position. The more it promotes universalistic objectives with narrow state support, the feebler it appears.

Instead of complying with the Court’s warrants, countries downplay them. The states signal they may not respect them in the future or openly defy them for domestic political reasons. After the warrants for PM Netanyahu and his ex-minister, Polish leaders welcomed Netanyahu’s visit, as did their Hungarian peers. Germany hedged its bets. French officials stressed a state had “obligations under international law with respect to the immunities of States not party to the ICC.”

Typically, the ICC’s four convictions have all been against citizens of member countries, whereas its cases against non-member state nationals have yielded almost nothing. Despite deposing indicted leaders, such as Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir, their successors have pulled back from cooperating with the Court.

Is there a way out?

A potential though unlikely U.S.-led scenario would be for the UN Security Council, armed with the sparingly used Article 16 of the Rome Statute, to temporarily freeze court investigations into the conduct of non-member state individuals. But even those U.S. observers who regard it as a potential trajectory consider it unlikely.

Toward a multipolar scenario

With the rise of China and the Global South, the above foundational conditions have dramatically changed in the past eight decades. In effect, the broadest state support and most effective implementation can only be actualized in a trajectory marked by multipolarity reflecting the existing global economic, political and military conditions—not those that prevailed 80 years ago.

In the multipolar scenario, the ICC trajectory would no longer be based on the West’s unipolarity. The UN Security Council and its permanent members could retain their role, but it should be augmented by the new conditions of multipolarity; that is, the increasing role of the world’s largest emerging and developing economies.

The history of human rights law is the story of the progressive efforts of the Global South to hold the West fully accountable for the pledges consistently and systematically violated. Certainly, the West doesn’t have a monopoly on genocides, but the latter are inherent in its colonial legacies, its efforts to dilute the scope of the Genocide Convention in the late 1940s and the suppression of genocide prosecutions through the Cold War and the post-9/11 wars.

From the standpoint of the Global South, the appeal of the South African genocide case against Israel is, at least in part, in that it highlights the role of colonial atrocities as a prelude to the killing of six million Jews in Europe and subsequent millions in the Middle East, Asia, Africa and elsewhere.

Realistically, the only long-term solution to ensure appropriate inclusive global governance is to accommodate the role of emerging and developing economies in the existing international regime.

The current regime is a relic of the 1945 “victor’s justice.”

For a copy of The Obliteration Doctrine: Genocide Prevention, Israel, Gaza, and the West by Clarity Press, click here. Available also via Amazon US, Amazon Canada, Amazon UK, Barnes & Noble, Indigo, Bookshop etc. Available already as pdf and e-book, the book will be released on August 1.