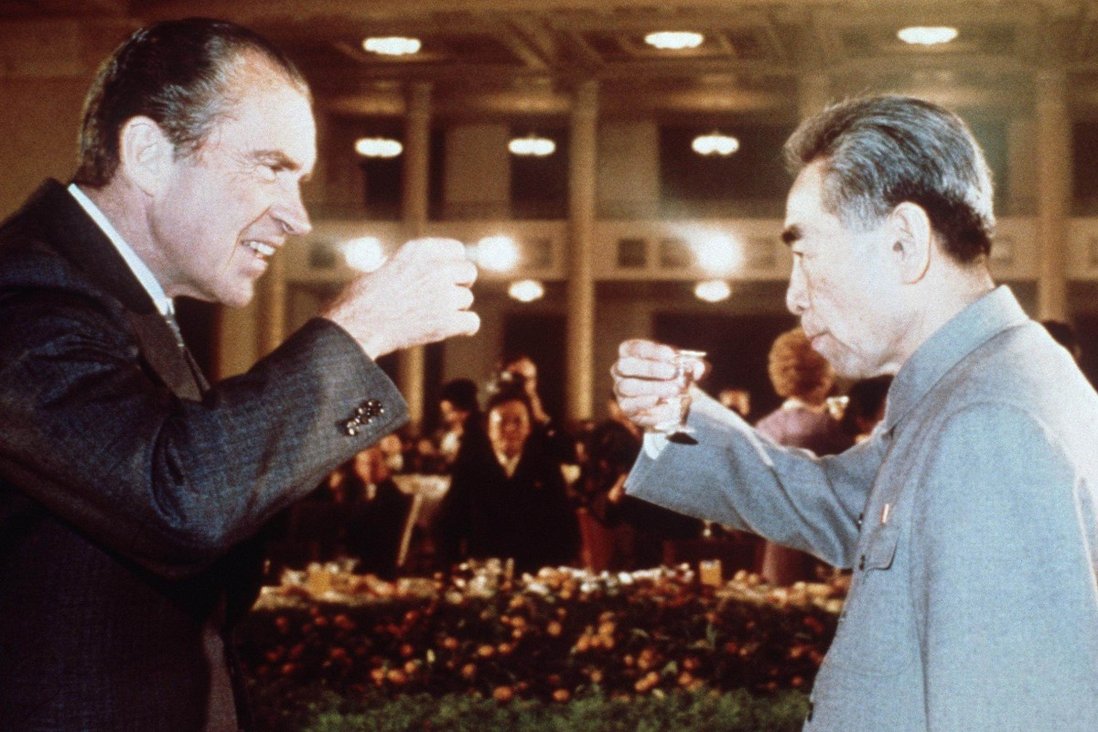

President Nixon’s historic visit to China in February 1972 was described at the time as “the week that changed the world.” While perhaps hyperbole, there is indeed truth in this characterization—for three principal reasons.

First, it ended the 22-year estrangement and complete lack of contact between both the governments and the people of China and the United States. It would take another seven years before official diplomatic relations would be consummated under the Carter administration, which in turn opened a wide variety of direct ties between our two societies: academic, business, tourism, sister cities and states/provinces, scientists, militaries, and various government departments, etc. Thus, it was really Presidents Carter and Reagan who really consummated the relationship and developed broad and substantive relations between our two societies, after Nixon opened the door.

Second, with the American opening to China, other governments around the world which had been part of the previous U.S. policy to isolate and contain China, were now free to open their own relations with the People’s Republic. Thus, in a real sense, the Nixon visit not only opened U.S.-China relations, but it also did much to open China’s own doors to the world (it had been previously almost completely isolated).

In this context it is also important to note that ending China’s international isolation was one of the animating reasons for his historic outreach and pathbreaking trip to China. Overlooked at the time was the way Nixon described China in an October 1967 article in Foreign Affairs. In it Nixon opined:

Taking the long view, we simply cannot afford to leave China forever outside the family of nations, there to nurture its fantasies, cherish its hates and threaten its neighbors. There is no place on this small planet for a billion of its potentially most able people to live in angry isolation.

This was the vision for integrating China into the post-World War II global order—truly a strategic goal with global consequences, one that seven subsequent presidents (until Donald Trump) subscribed to. It took the better part of five decades to institutionally embed the PRC into the international order, but generally speaking it can be concluded that Nixon’s call has largely been met.

Third, the Nixon visit was a strategic stroke of genius and fundamentally altered the balance of power in the so-called “strategic triangle” (U.S., China, Soviet Union) at the time, aligning America and China against Moscow. That, in turn, led over time to the weakening of the Soviet Union, its collapse, and end of the Cold War.

Prior to the Nixon-Mao opening, both the United States and China viewed the Soviet Union as an immediate military threat, but also as an expansionist power. Beijing in particular realistically feared a nuclear and/or conventional attack following the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia and pronouncement of the “Brezhnev Doctrine” (which falsely rationalized Soviet intervention in other socialist states to “save socialism” from “counterrevolutionary elements”). Moscow was also supporting insurgent movements and proxy regimes across Asia and Africa at the time, competing with both American and Chinese proxies. By opening ties and aligning with each other, increased geostrategic pressure was brought to bear on the “Polar Bear” from several directions.

This rationale provided the “strategic glue” for the relationship—but it only lasted for a decade. In 1982, China’s announced its “independent foreign policy” at the Twelfth Party Congress—which was codeword for a more equidistant rebalancing in Chinese foreign policy between the U.S. and Soviet Union. Deng Xiaoping still had three demands of Moscow to renormalize bilateral relations (the three conditions were: severing Moscow’s alliance with Vietnam, removing its military forces from Vietnam, and stopping support of Hanoi’s occupation of Cambodia; drawing down Soviet forces along the Sino-Soviet border to the level of 1964, and withdrawing them from Mongolia; and withdrawing its occupying troops from Afghanistan), which had been ruptured since 1962. Beginning in 1983 Deng began the step-by-step process of rapprochement with Moscow, which accelerated once Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in 1985. By May 1989, all of Deng’s conditions had been met and Sino-Soviet relations ended their hiatus—and along with it the central geostrategic rationale of Nixon’s visit. This was two years before the collapse of the Soviet Union and official end of the Cold War. Subsequently, the Sino-American relationship lost its “strategic glue” and has never found a new substitute since.

While “the week that changed the world” remains a hyperbolic caricature, there is still truth in it—if measured by the fact that it did much to open China’s doors to the world, which was fundamental to China becoming the superpower it has become today. But it was also true in that it reactivated ties that had been dormant between the American and Chinese peoples, and it opened a fifty-year period of peace between the two countries following hot wars in Korea and Vietnam. In these respects, it certainly changed the world.

Today, fifty years later, while cooperation continues in several sectors—business, academic, science—it has shrunk across the board, while the competitive dynamics have grown. Both sides perceive the other in increasingly negative, even hostile, terms. The American public’s perceptions of China are near their lowest point ever, and Chinese views of America are also quite negative. Yet, down deep, there remains an intrinsic attraction between the two peoples. The pendulum could swing in a more positive direction again.