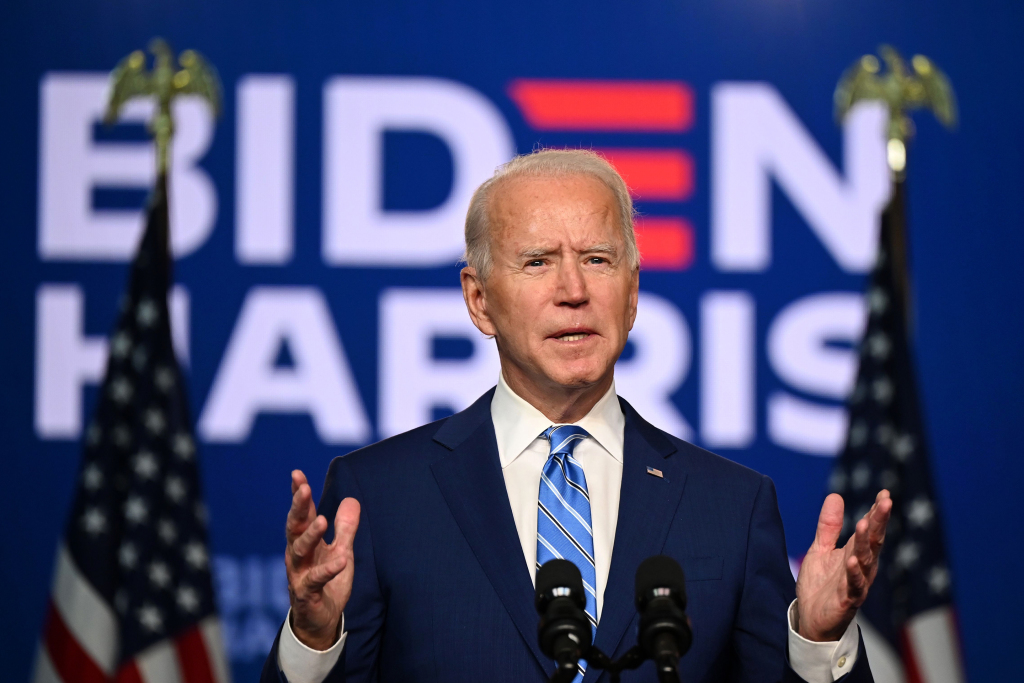

The unexpected popularity of Donald Trump in the U.S. presidential election prevented the landslide for former vice-president Joe Biden that had been predicted by polls and the mainstream media.

Now, Trump’s refusal to concede and his declaration that he will go to court to overturn the result signals that hostility will likely remain between the two sides. Trump’s case, such as it is, rests on a claim of fraud that experts say is untenable. Fraud is vanishingly rare in U.S. elections, and recounts virtually never alter results.

More votes were cast in this election than in any other in U.S. history, and Biden prevailed by a margin of more than 4.3 million. That’s not overwhelming, considering that nearly 129 million votes were cast.

But the strikingly even division suggests a need to explore the underlying trends in American society that appear in this unusual election and how they may affect U.S. policy toward China in the future.

The most important factor requiring notice is that the world may have to deal with a more divided United States in the years to come. Trump’s victory in 2016 heralded a historical trend of anti-globalization and protectionism that had been simmering for a long time, and he seized the political reins of the most powerful country in the world and shook up the established state of affairs practiced by most Western countries since the end of the Cold War.

In the U.S., it’s a virtual cliche that the loss of the middle and lower classes and outsourcing of jobs triggered the rise of populism and anti-establishment sentiment that propelled Trump to the White House. Trump, with his “America first” slogan, his disdain for the elite and his animosity toward the media, has further divided the country along party lines. At the same time, the radicalizing of the Democratic Party’s left wing has aggravated the gap and made the political polarization even worse.

The spread of the coronavirus has further amplified this division rather than cemented it. From the big question of how to deal with the bug — whether to protect people through a lockdown or save the economy by staying open — to seemingly minor questions about whether or not to wear a mask or maintain social distance, each party has its own policy lines. It seems the two cannot reach any meaningful agreement even on matters of common sense.

The old sore of racism has begun to fester again in American society. The Black Lives Matter movement, coupled with other turmoil and unrest, was instigated by the left in Trump’s telling, and “law and order” have returned as Republican buzzwords.

As the election neared, the method by which ballots are cast — in person or by mail — became contentious, even though voting by mail was well established and fraud-free across the country. But Trump promoted his baseless spin, sowing the seeds of a legal challenge after the election.

No matter how the deadlock is resolved in the days to come, the divisions in U.S. society will only widen as their leaders turn to governing and the people return, insofar as possible, to normal daily life. The mainstream media’s siding with the leftists can only complicate its relationship with conservatives and divide the country all the more.

This political dilemma actually has two structural causes that are difficult to overcome. First is the loss of manufacturing jobs to an efficient global supply chain. Both Obama and Trump made efforts bring companies back home from overseas but met with little success. With Biden coming into office, the trend of trade protectionism will be lessened somewhat, along with pressure to decouple from China. This is certainly a good sign for the world, but it will not help to ease the problem of outsourcing.

Second, the political polarization will worsen after the turbulent election. The U.S. system of checks and balances, which has been regarded as a fundamental aspect of U.S. democracy, actually sacrifices the efficacy of government and at the extreme helps reinforce political tribalism.

Francis Fukuyama once pointed out that the decay of the U.S. political system is the result of too much populism and the ensuing loss of balance between the three core elements of a successful society: effective government, democracy and the rule of law. Too much democracy squanders the power of government, and polarization undercuts the rule of law.

The dilemma facing the U.S. today is actually nobody’s fault but rather the legacy of the U.S. system itself. Trump has asked the right question but made things worse rather finding answers. With Biden, the cause of democracy will be ignited once again across both the U.S. and abroad, and under the influence of radical leftists inside his government, his agenda may tend to be middle-left — far away from the conservative side.

Meanwhile, China should keep in mind that Biden’s space to create a healthier and more balanced relationship is limited by a strong opposition party and a divided society. Furthermore, as a country constantly suffering from domestic division and internal struggle, the U.S. has to focus more on domestic matters, regardless how international Biden wants to be. It may be smarter for him to link business relocations with the forging of a multilateral trade agreement such as the TPP and exclude China once again. He may also likely use anti-China sentiment to galvanize the minimal domestic consensus that exists — something China should keep in mind.