Click to read the latest China-US Focus Digest

President Xi Jinping recently called for a more “credible, lovable, and respectable China” in an address to senior party officials.

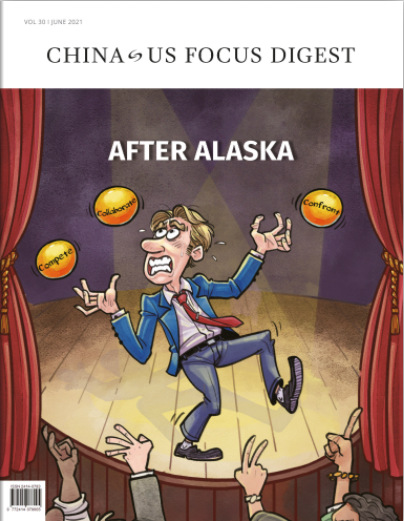

Some argue that his comments herald a genuine pivot in Chinese diplomacy, from the bellicose, antagonistic overtones of the “Wolf-Warrior diplomacy”, to a more moderate, pragmatic approach reminiscent of the taoguang yanghui era of the 2000s and early 2010s.

Others have argued that these comments were diplomatic pleasantries at best, indicating no more than merely a cosmetic response to China’s rapidly deteriorating international reputation amongst certain quarters of the world. China has risen considerably, and with it, so must its willingness to stand up to its enemies.

I am as uninterested in crystal gazing as I am in engaging with hyperbolic, often disingenuous online debates over Chinese foreign policy. Instead, I’d like to outline three key strategies – constructive amendments – through which China can indeed become more lovable.

Firstly, it is in Beijing’s interests for their more vociferous diplomats to tone down their language. Such diplomats ought to refrain from engaging in elaborate Twitter spats involving potentially dubious photographic “evidence”, and should outline China’s interests and concerns through more amicable – not capitulatory, but amicable – language. These measures can help repair the public image of China abroad. Chinese diplomats need not be aggressive or hyper-defensive – renowned, established pioneers of 21st century Chinese diplomacy, such as Cui Tiankai and Fu Ying, are known for their willingness to engage in genuine, forthcoming dialogue and exchanges over the reservations and shortcomings of the Chinese state. Doing so neither compels them to forego critical wants of the country, nor enter into unbecoming positions of compromise.

Indeed, restoring track-II diplomacy is vital, but this simply cannot happen when guns are blazing and shots are fired. Think-tank leaders, academics, and diplomats from both sides of the Pacific, who have found themselves under the cross-fire between the ongoing U.S.-China spat, have become increasingly reticent in engaging in mutual dialogue, fearing the opprobrium of hard-liners in Beijing and hawks in Washington. A more lovable China could take the lead in re-opening and re-establishing the space in which balanced, moderate discourse can be held.

Only through conversations aimed at clarifying the signal from the noise, that cut through the bombastic rhetoric, could bilateral relations between American and Chinese civil societies be genuinely repaired. Lifting bans on journalists, easing restrictions on academic conversations and conferences in the Mainland, and extending private invitations to reconcile to key diplomats the country had openly chided, could be instrumental in achieving this end.

An objection that is often levied here is that a softer approach to diplomacy would require China to forego its core interests. This is a misguided, albeit understandable, rejoinder.

Here and secondly, China must differentiate between issues on which mutually beneficial compromises can be sought, and critical issues on which no concession is politically feasible or desirable.

The two lists are not equivalent, and conflating the two could send very dangerous signals to the country’s foreign counterparts, and cause the country to over-exert itself in defending fundamentally non-essential interests. China is right to seek to defend its domestic interests, stability, and sovereignty – yet doing so should not, nor need not, come at the expense of its openness to foreign capital, international cultural values and mores, and political pluralism, both abroad and domestically.

In any case, where such compromises cannot be settled upon, China would still benefit greatly from communicating its answers transparently and comprehensively, as a means of assuaging the worries of its sceptics, and responding to the challenges of its external critics. Diplomats and politicians alike must do so through terms of reference and value propositions that the West can understand, as opposed to language it believes (perhaps correctly) its domestic audience would ardently embrace. Flexible diplomacy is not akin, in any shape or form, to kowtowing – it is instead what a responsible, flexible, and confident ascendant power should present as a core prong of its international statecraft.

Take a concrete example here – the Belt and Road project has been extensively portrayed as ostensibly culminating at “debt trap diplomacy”, with its critics framing China as offering predatory loans that ensnare its allies and partners. In reality, it’s far more complex than that. China would benefit from greater transparency and accountability over its terms of debt, criteria for selecting projects in which to invest, and the implicit strings attached to overseas aid.

There’s a curious Chinese saying that literally insists, “The Clean Will Come Clean” (清者自清). Yet this is not how international perceptions – at an age of social media – work. Echo chambers, increasingly bifurcated international media, and discursive isolation have left the country in a largely defensive position when it comes to international debates. China is portrayed as a mortal enemy and existential threat to the Western liberal democratic order, even though such claims are wildly exaggerated and out-of-touch with reality.

Thirdly and finally, China must also take a long and hard look at its soft power efforts. The 2008 Beijing Olympics saw China enter into a new era as an international player, as a power that was viewed as affluent, respectable, dignified, yet also admirable for its capacity to put on a dazzling performance by playing host to the most prominent international competitive event in the world.

Thirteen years on, soft power remains a work in progress. Whether it be the extent to which Chinese movies and culture captivate global audiences, or the attractiveness of Chinese values and the China Model (if there even is one), or the global awareness of how China’s burgeoning millennials and middle class could really usher in a new era of sociocultural transformation, there is much that remains untold and unheard of on the international level.

It is tempting to fault “media bias” for the vitriolic backlash towards China – but media bias is part and parcel of global politics. A pitfall that some in China have fallen for is to treat external messaging as a means to internal communication. It is high time for the two to be bifurcated – what works in riling up the crowds internally, may not work in convincing the world of China’s merits.

If China is to become more lovable, it must learn to love itself first – and embrace itself with the phlegmatic, restrained confidence that a power of its stature should and can exhibit.