The current deglobalization policy of the Trump administration in the form of tariffs, as well as its disregard for multilateral rules, will only lead to a slowdown in American economic growth. It will undercut the country’s technology advantages and hurt American families.

President Donald Trump’s worldwide tariff is the basic tool he is using to fight globalization. He has been blaming globalization — vehemently == for leading to a huge trade deficit, job losses, manufacturing losses and the decline of middle-class income in America. His basic logic goes this way: High tariff walls will block imports, cutting down trade deficits, thereby protecting domestic jobs and forcing manufacturing to return to the United States. This will increase middle-class income, Trump thinks, making America great again at the cost of globalization.

But whether Trump and his team realize it or not, the robust economic and technological growth in America over recent decades have come precisely because of globalization.

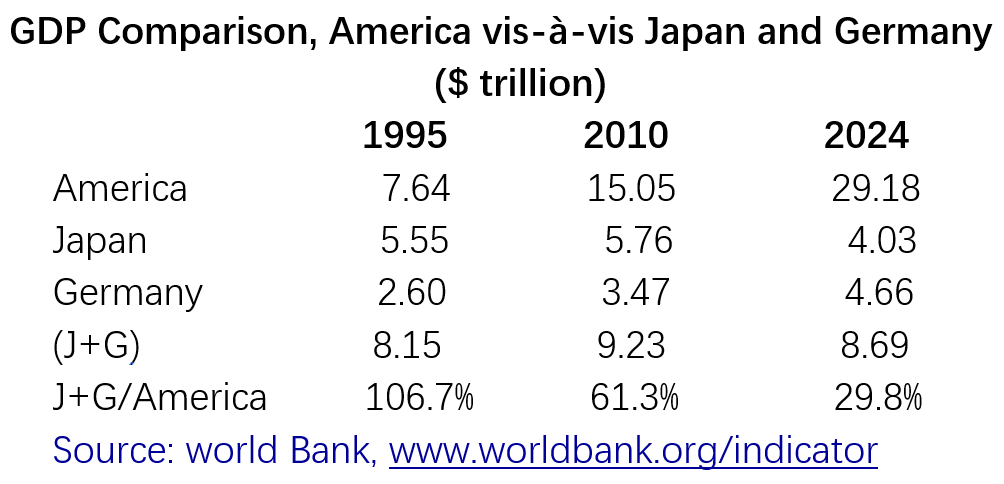

The American GDP almost doubled in 15 years (1995-2010, the super globalization period), from $7.64 trillion to $15.05 trillion, or 4.7 percent growth per year. This fast tempo persisted in the 2010-24 period, a time of slow globalization. America’s GDP hit $29.18 trillion last year and nearly doubled again during the 14-year span, or 4.8 percent per year. It even accelerated slightly.

In 1995, the combined GDP of Japan ($5.55 trillion) and Germany ($2.6 trillion) was $8.15 trillion, 6.7 percent greater than the United States. Fifteen years later, Japan and Germany combined for a GDP of $9.23 trillion, or 61.3 percent that of America in 2010. By 2024, another 14 years later, the combined GDP of Japan and Germany was less than 30 percent that of America.

Just a decade ago, the European Union had a larger GDP than the U.S., but by 2020 they were about equal. By 2024, the combined GDP of the EU and United Kingdom was 20 percent less than America.

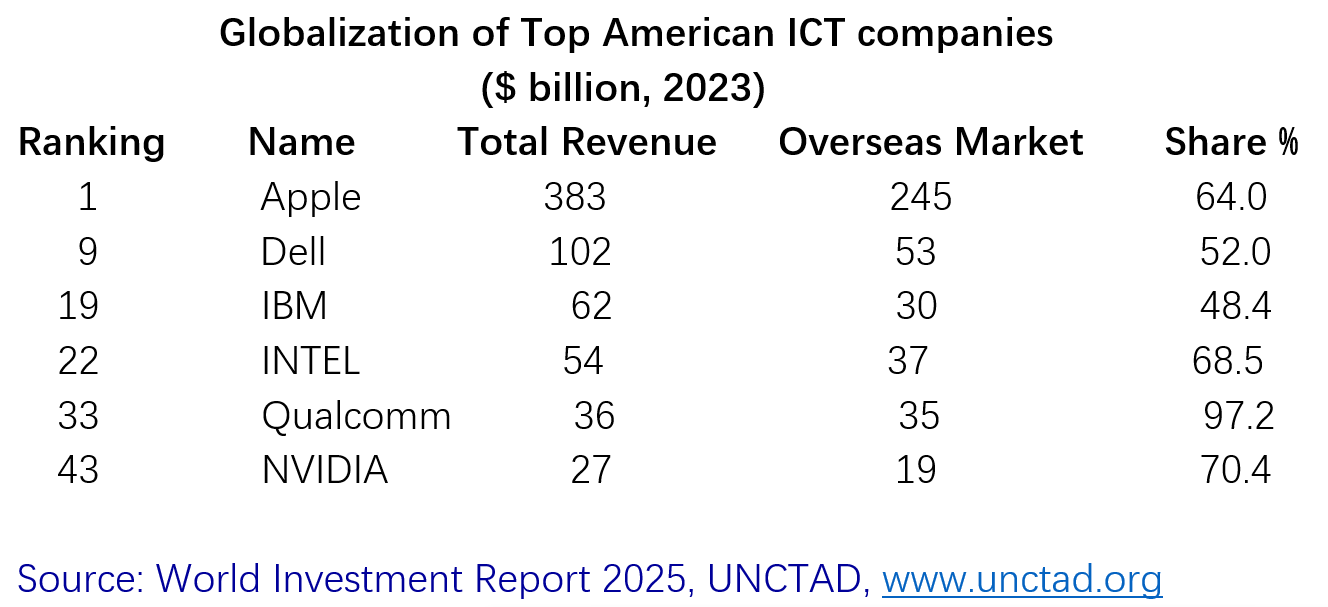

The key driver of the American economy’s strong growth has been the cutting-edge advantage of technology, including information and telecom, the digital economy and artificial intelligence. Ironically, all the leading players depend heavily on global markets. According to the World Investment Report 2025, released by UNCTAD, America accounts for 56 enterprises among the world’s top 100 digital enterprises, and had all of the top four. Amazon was at the top, with total revenue at $573 billion, with $155 billion (27.0 percent) generated in overseas markets. Apple was No. 2, with total revenue at $383 billion. Of the total, $245 billion (64 percent) came from global markets. Ranking third, fourth and fifth in revenue from global markets were Alphabet (52.4 percent), Microsoft (49.5 percent) and Meta (63.0 percent).

America also had 29 enterprises among the world’s top 100 ICT companies. Their dependence on globalization is even more pronounced.

The conclusion: No globalization, no American success.

This paradigm is further confirmed by the fascinating growth of global direct investment flows into the United States since 2010. Total foreign direct investment inflow stock worldwide increased by $30 trillion from 2010 to 2024, and that of the U.S. accounted for $12 trillion, or 40 percent of the world total. By the end of 2024, the U.S. had a total FDI stock of $15.57 trillion, or 30.6 percent of the world total. During this period, the FDI stock in the U.S. grew by 354.9 percent, compared with 67.7 percent growth in Europe. Hence, the flooding of world capital has been a key driver of the U.S. economy, even during the slow globalization times.

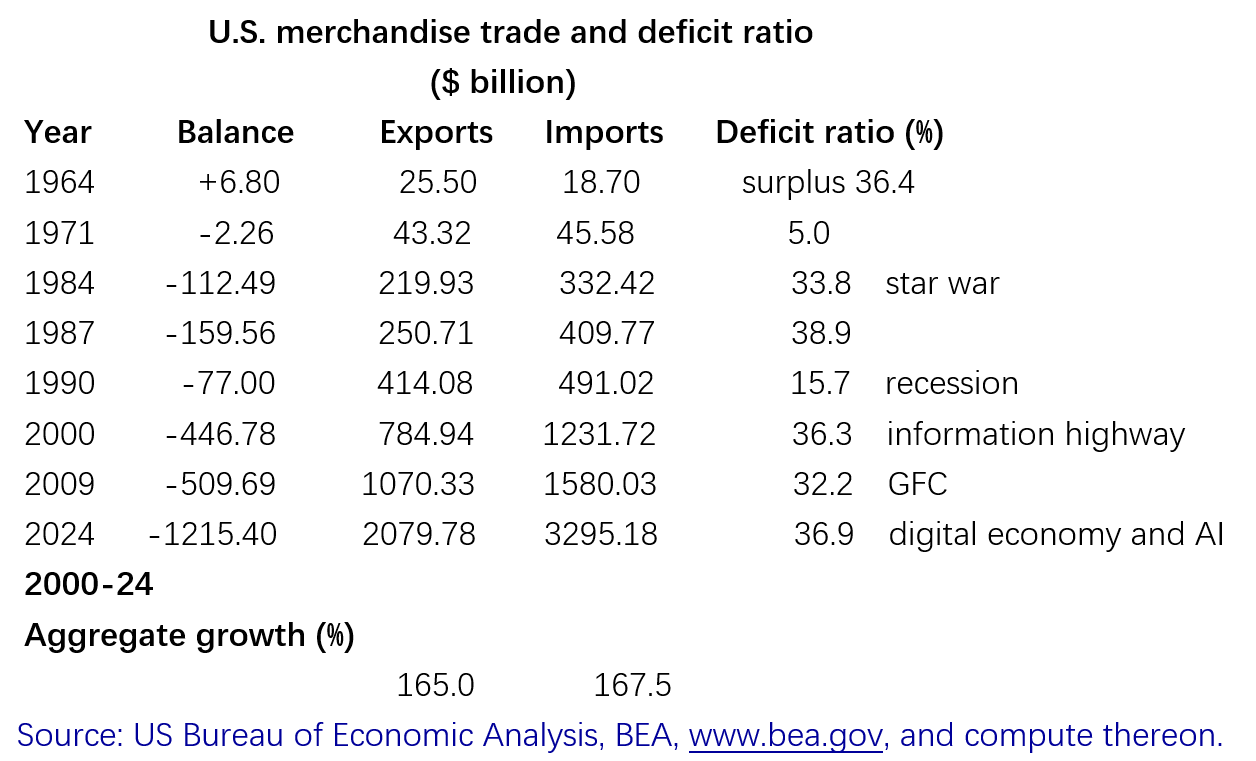

The American trade deficit is more related to the dollar and technology advancements. The U.S. led the world effort toward globalization and free trade since World War II. In the same globalization ecology, the U.S. had a huge trade surplus during the first postwar quarter-century between 1945 and 1970. The first trade deficit appeared in 1971 when President Richard Nixon abandoned the gold standard, which had linked the dollar to the precious metal. The subsequent dollar devaluations in 1971 and 1973 set a trade deficit pattern. Two other factors were the skyrocketing price of oil globally in the 1970’s and the strong advancement of technology and the economic boom after the late 1980’s.

The U.S. trade deficit ratio (deficit to imports) hit 38.9 percent in 1987 when the Ronald Reagan’s Star Wars strategy triggered a profound industry structural transformation. This pattern continued into the 1990s, when Bill Clinton launched the information highway strategy. After the global financial crisis, digital technology led to structural changes in American industry.

All those profound structural changes left the traditional lower-value-added products to outsourcing, leaving higher technology at home and resulting in much higher productivity and thus much faster economic growth. During this whole process, U.S. imports and exports kept growing at the same rate, resulting in a surprisingly stable deficit ratio over the past four decades. The U.S. trade deficit ratio in 2024 — 36.9 percent — was exactly the same as in 2000, and even lower than it was in 1987.

The U.S. trade deficit does not hurt the total international balance of payments, nor has it taken away American jobs. Because of the global dominance of the dollar and America’s strong economic growth, the huge current account deficit has been covered easily by the same huge surplus under the financial account. There has been no crisis of international payments. The jobless rate in 2024 was 4.1 percent, the same as in 2000 (4.0 percent), with both at their lowest point since the 1970’s, as the new technology created a large number of new jobs.

The rust belt is a particular case that shows the need for retraining and technology upgrading. It does not represent the whole picture of the United States, nor even the picture in other leading manufacturing states (California, Washington, Texas). Globalization over the decades has not brought down the income of American families, including the middle class. U.S. Census data show that, during the quarter-century from 2000 to 2024, American per capita disposable income increased from $ 28,171 to $63,441, up 125.2 percent. The problem lies in unfair distribution. Recent data show that the top 50 percent of American families took 97.5 percent of total wealth, leaving only 2.5 percent for the bottom 50 percent. The very high Gini coefficient in America is the real reason, as it is in most European countries, with even higher global market participation but much lower Gini coefficient generally, have little to complain about with respect to falling incomes.

The current deglobalization policy of the Trump administration in the form of tariffs, as well as its disregard for multilateral rules, will only lead to a slowdown or stagnation in American economic growth. It will undercut the country’s technology advantages and hurt American families. Trump will realize this wrong direction for sure, sooner or later.