Global trade is evolving, not ending, as structural limits on U.S. protectionism and the rise of regional agreements beyond U.S. influence sustain economic integration. While the U.S. remains the dominant power, the U.S.-centric trade regime is gradually declining.

We are often told by commentators that the return to power of U.S. President Donald Trump marks the “death knell” in globalisation – that the halcyon days of unbridled free trade, which had exploded subsequent to the end of the Cold War in 1991, have not only peaked, but are fundamentally over. At times like these, to speak of free trade as virtuous appears to be not just empirically atavistic, but also – perhaps more importantly – politically toxic.

Thanks must go to the wave of populism that swept Trump, alongside Orban, Johnson, Milei, to power, and which also fueled xenophobic movements such as the AfD in Germany or National Rally in France. Such shifts have in turn been exacerbated by the fracturing and rearrangements of supply chains in reaction to the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, as well as heightening barriers to trade across major economies, e.g. the U.S., Europe, and China.

The “death knell” narrative is not wholly erroneous, though the frequent rehashing of it tends to lead to fatalistic assertions that do not conform with the facts at hand. Whilst Trump’s second term has seen the populist, who once proclaimed that his favourite words in the dictionary included “tariffs”, declare an ad hoc round of “reciprocal tariffs” on April 2nd, he also conceded to the 90-day suspension of the same tariffs seven days later.

The subsequent two months of developments were characterised by the all-too-familiar routine: Trump would threaten a drastic increase in tariffs against a particular trade partner, only for the bond and stock markets to react in cataclysmic panic, and for his allies to agitatedly press for capitulation; within weeks, he would back off and proclaim that a deal had been reached. Hence the adage: Trump always chickens out.

Why Trumpian protectionism will not fundamentally destroy global trade

The claim that Trumpian protectionism marks a fundamentally fatal blow to global trade, overlooks three important facts.

Firstly, whilst Trump may be predisposed towards more trade restrictions and limitations, he is also kneecapped by domestic political considerations. Though early signs certainly suggest that Trump’s erratic first 100 days have been less inflationary than anticipated, the real threat kicks in as he confronts the prospects of a declining stock market amidst escalating bond yields, in reflection of the systemic destabilisation of the long-held market wisdom that U.S. Treasury bonds are safe assets amidst macroeconomic turmoil. Pressure exerted upon him by domestic automobile manufacturers hampered by China’s weaponisation of rare earths has also contributed towards a drastic U-turn over recent weeks, as evidenced by the Geneva and London talks between the Chinese and American delegations.

Secondly, Trump’s victorious return is but a symptom – and not the sole cause – of much deeper antipathies towards free trade amongst disillusioned citizens in the post-industrial West. Within-country inequality has become increasingly preeminent, as compared with inter-country inequality – in reflection of the fact that even amongst the poorest of countries, globalisation has enriched a small yet significant crop of privileged elite, whose success is widely viewed as having come at the expense of the less privileged within their communities. Trumpism, rooted in moralised grievance, propelled by nihilistic rage, is hence a manifestation and beneficiary, but not prime promulgator, of such underlying dynamics.

Thirdly, the rest of the world is proceeding accordingly with forming new trade agreements in the absence of the U.S. Take the two natural resource-rich regions of Southeast Asia and the Arabian Gulf as examples. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) have been vocal in not just talking up but also committing to increasing bi-regional trade between the 10 and 6 economies, respectively. Projections suggest that GCC-ASEAN trade will surge from $13 billion in 2020 to $682 billion by 2030, clocking in at 7.1% annual growth per year over the ten years.

What is probably dead, however, is the long-unquestioned premise of the ironclad predictability and certainty of the economic “compact” (not Pax, for it was not wholly peaceful) of Americana: that the US would lead the world’s march towards free trade flows and economically open borders, in providing the public goods of trade revenue to aligned actors – in exchange for their broad geopolitical fidelity. It is high time for us to recognise that we should not conflate global trade with trade between countries with the U.S.

The end to the U.S.-centric global trade regime?

Notably, the destabilisation of the implicit compact does not thereby guarantee the “end” to a U.S.-dominated economic order. Even if it is to occur, the end to American global dominance would be a non-linear, uneven, and incredibly gradual process. It took over 200 years for the Western Roman Empire to complete its “decline” in earnest, with the toppling of the last Roman Emperor, Romus Augustulus. For now, the U.S. remains the dominant financial, military, and economic power in the world.

Those who assert that U.S. leadership is no longer viable, should think twice about qualifying their claims. Yet we are witnessing the beginning of the end of a U.S.-centric global trade regime – one where the U.S. serves as the primary progenitor and arbitrator of economic and commercial rules across the board. The persisting heft of the U.S. is not contradicted by the three following predictions.

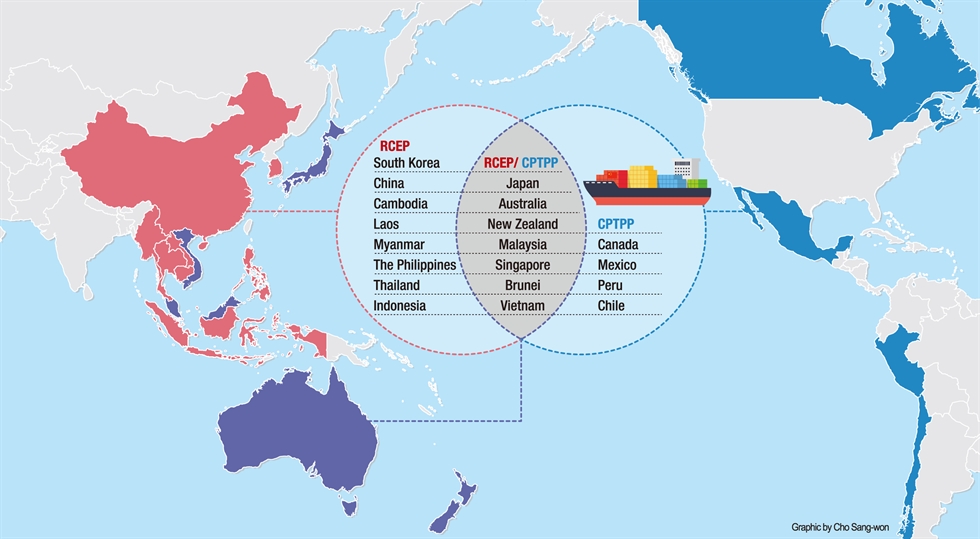

First, free trade agreements free from the U.S. will continue to rise and thrive. Upon taking office the first time, Trump immediately withdrew the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) – with the (subsequently debunked) presumption that the TPP members would take to conceding to American demands. The net result was the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a bloc in which the US was notably missing. Today, the largest trade agreement (in terms of total economic size and population) in history does not include the US – it is the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which benefits immensely from the technological advancements of China, Japan, and South Korea, as well as the manufacturing prowess of emerging powerhouses in Southeast Asia, such as Indonesia and Vietnam.

These agreements are not purely vacuous. Over recent years, the European Union and ASEAN have overtaken the U.S. to become China’s largest and second largest trade partners – with the “top prize” alternating frequently between the two blocs. In 2018, exports to the U.S. accounted for 3.5% of the country’s GDP; five years on, they amounted to 2.9% - a fairly sizeable decrease (by almost one-fifths) within a reasonably short span of time. As China continually diversifies away from the U.S., regional agreements including the manufacturing powerhouse would continue to thrive, albeit not without their fair share of side effects, as we shall see shortly.

Second, mini-lateral economic institutions drawing together countries from different geographical blocs would become precipitously prominent – not just in terms of direct raw trade, but also in shaping and determining currency and capital flows. The advent of BRICS+ is testament to the fact that economies that have had enough of unilateral coercion, cajoling, and castigation by the U.S. can and will seek closer alignment in trade regulations, capital flows, and commercial agreements. Whilst BRICS+ remains fairly underdeveloped at present, there exists much potential in the advent of cross-border financing of developmental and renewable energy projects, as well as intensified digital goods and service trade in the decades to come.

With that said, in pursuing mini-lateral integration with emerging economies, Beijing must also be wary of alienating key stakeholders in their domestic economy, as it had with more developed economies. The Sino-European Union relationship remains tendentious, not just in virtue of ideological or geo-strategic divergences, but also the broadly widening (over the past decade) trade deficit between the two blocs. European politicians in manufacturing-heavy economies (both of the past and at present) feel compelled to rhetorically castigate – and, at times, push back with policies – against what they perceive to be excessively cheap and competitive Chinese goods. Whilst talk of “over-capacity” is apparently politicised and political, there exists a grain of truth in the critique – which in fact coheres with Beijing’s long-term interests: China cannot and should not rely upon a wholly export-dominant approach to international trade – as it rises in stature and strategic status, the world expects China to shoulder the responsibilities of consumption, whether it be via imports, or redirecting some of its exports to its burgeoning middle and upper-middle classes.

The third and final observation concerns the role played by low-tariff and open economies. In an age where tariff-raising is once again in vogue, economies that are willing to stick to their guns of minimising obstacles to trade, can and stand to benefit. Hong Kong, for one, is a free-port, as mandated by the city’s mini-constitution, the Basic Law. It has opted out of imposing reciprocal tariffs against American exports, which China – as the mainland – has. Should tariffs remain much higher than their historical averages between the two sides of the Pacific, there exists room for Hong Kong to resume its historical role of serving as an entrepot for re-importing and re-exporting of American and Chinese goods, respectively, to mainland Chinese and American tourists. It is high time that economically liberal regions stepped up to honour the ethos of barrier-free access to exchanges of goods and services.

Free trade can yet live on – albeit in a different form.